“US drinking water widely contaminated with ‘forever chemicals’: environment watchdog,” read the Reuters headline. It is based on a report by the Environmental Working Group (EWG), a lobby group with an irrational fear of chemicals of any variety and in even the smallest of doses.

It is afraid of genetically modified organisms, for example, a position which I have debunked, time and time and time again. They also monger fear about pesticide residues on food. A healthy diet containing lots of fruit and vegetables actually contains an estimated 10,000 times more natural pesticides than residual pesticides applied on the farm. Very few of these natural pesticides have ever been tested for health effects, but they are equally likely to be carcinogenic as synthetic pesticides, when fed to lab animals in high doses unrelated to likely exposure levels in humans.

The chemicals creatively described as “forever chemicals” are more properly known as poly- or perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS), a class of about 5,000 different chemicals notable for their resistance to environmental degradation. Because they don’t react with much, PFAS chemicals have been very widely used since the 1940s in products such as fat- and water-repellent coatings on food packaging, weather-proof clothing, stain-proof carpets and upholstery and firefighting foam.

The idea that they do not degrade is supposed to instil fear, but that plays on a common misconception. They do not degrade because they are not very reactive. In order to cause harm, chemicals generally have to react with other chemicals. Otherwise, even if they do get absorbed in soil, water or animal and human tissue, they do very little.

A similar mistaken fear involves nuclear radiation. Substances that take “tens of thousands of years” to decay are far less dangerous than substances that decay rapidly. Besides, many toxic chemicals, like heavy metals, do not decay at all, and remain in the environment for far longer than “tens of thousands of years”.

If you dig into the EWG’s campaign against PFAS, you’ll find they claim that the US Air Force, which used the chemicals in firefighting foam, has been aware of their toxicity since 1973. Not only does it neglect to mention anything about the exceptionally high doses used in the tests, but it also neglects to mention that the Air Force experiment (on trout) found that distilled water was equally toxic to the fish. The EWG refers to a 1976 study by Navy scientists, which, if you actually read it, concludes that the substance has a relatively low level of toxicity, which is “not considered to be a problem”.

The EWG claims that 3M, which manufactures ScotchGuard, “notified” the EPA that “PFAS were toxic”. In support of this claim, it refers to a New York Times article from May 2000, which says nothing of the sort. In fact, it quotes both the EPA and 3M officials saying there is no evidence that the chemical in question poses any threat to human health. The only reason 3M chose to remove the chemical from its product is its environmental persistence, which might lead to entirely speculative harm in the future. The only reason the EPA was worried was a study in rats fed extremely high daily doses of the substance, not toxicity in humans.

Clearly, EWG blatantly misrepresents its sources in order to advance the claim that PFAS are known to be harmful to human health.

To get a copy of a paper on how to avoid PFAS exposure, they wanted my email address for marketing purposes, and promptly redirected me to a donation page. They repeated their appeal for money in the email I received. EWG might be a non-profit, but it certainly employs a lot of people, and their income depends on the willingness of fearful members of the public to sacrifice their privacy and part with their money. Campaigning on environmental issues is big business.

The problem with testing chemicals is that almost all chemicals are toxic in some dose. As Paracelsus observed (albeit a little simplistically), the dose makes the poison. This is true even for pure oxygen or clean water. About half of all chemicals, whether natural or synthetic, have proven to be carcinogenic at a high enough dose, and the rest – including substances like vinegar and salt that we commonly consume – are probably toxic in some other way.

The real question is not whether there is some association between high levels of consumption and adverse effects in laboratory animals. Not all animals react to toxic chemicals in the same way. For example, some tick and flea treatments that dogs tolerate quite well are extremely toxic to cats. All you can conclude from an animal study is that a substance might cause harm to humans at some dose. It could be better or worse, or not cause any significant harm at all.

So far, weak associations are all they’ve found. A recent paper about “emerging insights into health risks” of PFAS chemicals, for example, relies on speculation about “untested effects”, and blames the inability of studies to find mortality effects in workers that regularly handle the chemicals on the “healthy worker effect”; that is, the supposition that unhealthy workers don’t participate in health studies. On studies that did find evidence suggestive of health risks, the paper warns that there are several factors that “limit the conclusions that can be drawn from this evidence”.

Ergo, they have found some results worth investigating further, but have not found very much to warrant widespread panic.

A supposed association between prenatal exposure to some PFAS chemicals and (slightly) lower birth weight – which the EWG states as fact – turns out to be mostly a confounding effect, in that pregnant mothers with reduced kidney function tend to have higher blood serum levels of PFAS, as well as babies with lower birth weight, so PFAS doesn’t cause the lower birth weight.

A study on possible immuno-suppressant effects of high concentrations of PFAS chemicals notes that it was “not possible to attribute causality”. Another study published only months later found that the effect was much smaller than the first study had found. Both involved particular substances that have largely been phased out of industrial use in any case.

And so it goes on. There are a few weak studies that “suggest” a “possible association” between some PFAS chemicals and this or that health outcome, but nothing to suggest an emerging public health crisis that somehow, nobody noticed for more than half a century, despite PFAS chemicals being very widely used.

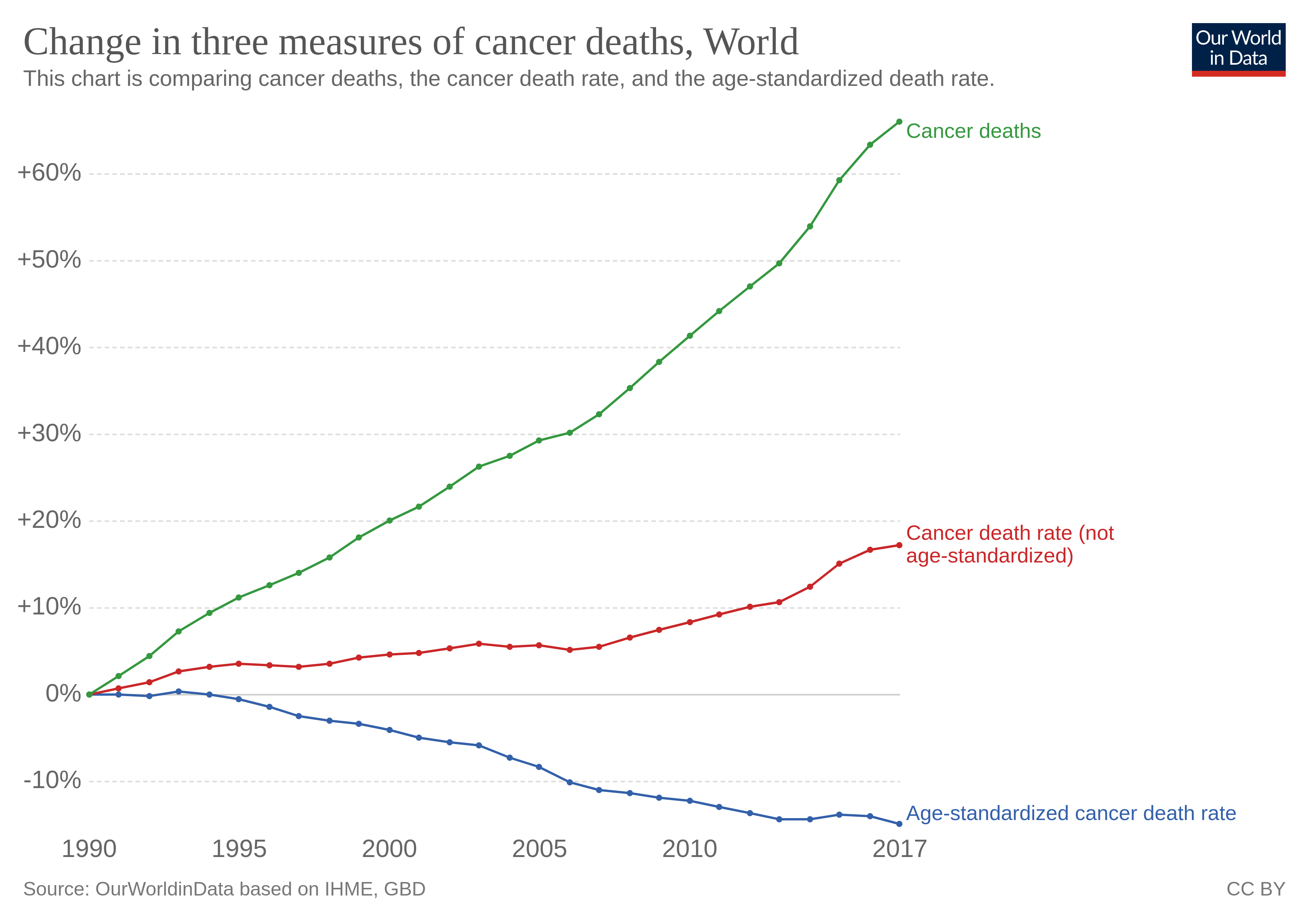

There is a widespread belief that the increase in the use of synthetic chemicals in recent decades, and the environmental pollution associated with it, has led to a rise in cancer rates. This is not true, however.

Although the cancer rate has increased in nominal terms, this is entirely accounted for by the fact that we are healthier and less likely to die young of infectious and other preventable diseases. If you adjust only for ageing, the cancer rate shows a slow but steady decline.

If there is a health crisis caused by exposure to industrial chemicals, it sure doesn’t show up in the numbers.

Besides environmental lobby groups, there is another industry that profits greatly from scaremongering about chemicals that pose little proven risk to human health or the environment.

Land and groundwater remediation is a large and growing industry. In the US alone, it comprises about 4,500 businesses, accounting for $17-billion in revenue. Worldwide, estimated remediation industry revenue is $80-billion.

In the past, it used to have plenty of large-scale toxic waste cleanups to keep it occupied. Although pollution remains a concern in many parts of the world, modern industry is, by comparison with that of a generation or two ago, much cleaner.

Take oil spills, for example. There has been a sharp decrease in the size and number of spills over the past 50 years.

This means that the remediation industry needs to drum up new business. It has had to expand into cleaning up pollutants that were previously considered too minor to throw a lot of money at.

Perpetuating a fear of synthetic chemicals in the environment plays right into the pockets of this industry. It creates public demand for politicians to pass laws that force “overdue action” (as the EWG does). Legislation creates lots of lucrative new business for companies that offer remediation services.

It will come as no surprise that a search for PFAS remediation turns up dozens of links to companies that offer cleanup services, training or consulting (including large PFAS producers such as 3M themselves).

Lobby groups such as the EWG like to pretend that they exist to protect you from governments and businesses that don’t care about your health, but they serve a callous profit motive, too. Remediation companies rely heavily on such lobby groups to do the scaremongering for them, and governments rely on them to raise issues about which they can be seen to be “doing something”.

Getting scary phrases like “forever chemicals” into Reuters news headlines is the way they operate. Which average consumer, who knows little about chemicals except “they’re bad”, is going to look at that headline and think it’s not a big deal? No, they’re going to donate to the environmental lobby and demand that their local politicians “act now”, which is exactly what the remediation industry wants.

Some pollution problems are real and are worth the cost of cleaning up. Some pollutants do pose significant risks to human health. When you see scary catchphrases like “forever chemicals’ ”, however, it pays to be sceptical. Often, entire environmental campaigns are built on the flimsiest of evidence, or even on outright misrepresentation, as we’ve seen in this case.

Turns out, “forever chemicals” are nowhere near as scary as the environmental lobby (and Reuters) would have you believe. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider