At the risk of stating the painfully obvious, South Africa’s energy sector is in crisis. However, beyond the immediate problems of crippling debt, bloated payrolls, corrupt procurement deals and lack of maintenance, the question of what the country’s energy mix ought to look like, remains.

In his budget vote speech of 11 July 2019, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe put nuclear energy firmly back on the table.

“The Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) is in the process of being finalised at Nedlac,” he said. “In September 2019, it will be tabled before Cabinet for approval. The IRP considers a diversified energy mix that includes all forms of energy technologies such as cleaner coal, nuclear, gas, hydro, renewables and battery storage.”

He added: “As a country, we must avoid the currently polarised debate on energy, pitted as coal versus renewables. The debate should be about the effective use of all the energy sources at our disposal, to achieve security of supply.”

He said planning for new nuclear power plants should start now, and that “Koeberg demonstrates the benefits of nuclear power, give (sic) reason to South Africa continuing with the nuclear expansion programme.”

This, of course, elicited an outraged editorial from one of Daily Maverick’s environmental journalists, but since they hang their story on a television series called Chernobyl which, though entertaining, has been criticised by experts over its heavily dramatised portrayal of the impact of nuclear radiation, it’s probably best to ignore it.

South Africa has long pursued the expansion of its nuclear programme. In 2007, under president Thabo Mbeki, Eskom announced plans to double its generating capacity to 80-gigawatt electrical (GWe) by 2025, including 20GWe of new nuclear capacity. This would raise nuclear energy’s contribution to electricity generation from 5% to more than 25%, while slashing that of coal from 87% to below 70%.

The programme would start with up to 5GWe of third-generation pressurised water reactors (PWRs), which offer improvements in fuel technology, thermal efficiency, passive nuclear safety systems and standardised or modular designs for reduced maintenance and capital costs, compared with the second-generation PWR design of the Koeberg Nuclear Power Station. They are entirely unlike the older RBMK design used at Chernobyl.

Building was to begin in 2010 and be completed by 2016. In 2008, third-generation designs built by consortiums led by the French firm Areva (whose predecessor helped to build Koeberg) and the US company Westinghouse were shortlisted. The same year, however, the project was put on hold due to a lack of funds.

In the Integrated Resource Plan for 2010 to 2030, published in 2011, provision was made for 9.6GWe of nuclear capacity to come online between 2023 and 2032. Eskom, however, knowing that it couldn’t afford to buy a dynamo for a bicycle, said it would be looking a lower-cost option, including second-generation designs from China, South Korea and Russia. An initial co-operation agreement was signed with Russia’s Rosatom, which was widely, but incorrectly, interpreted as a secret and unauthorised procurement agreement. Similar agreements were subsequently signed with France and China, outlining what each country could provide if selected to participate in South Africa’s build programme.

Misunderstanding of the nature of the Rosatom agreement, a spurious cost figure of R1-trillion that had no basis in fact, and well-founded distrust of the corrupt president Jacob Zuma, turned even some pro-nuclear commentators against the build programme. In mid-2018, Zuma’s successor, Cyril Ramaphosa, nixed the idea of new nuclear capacity as too expensive.

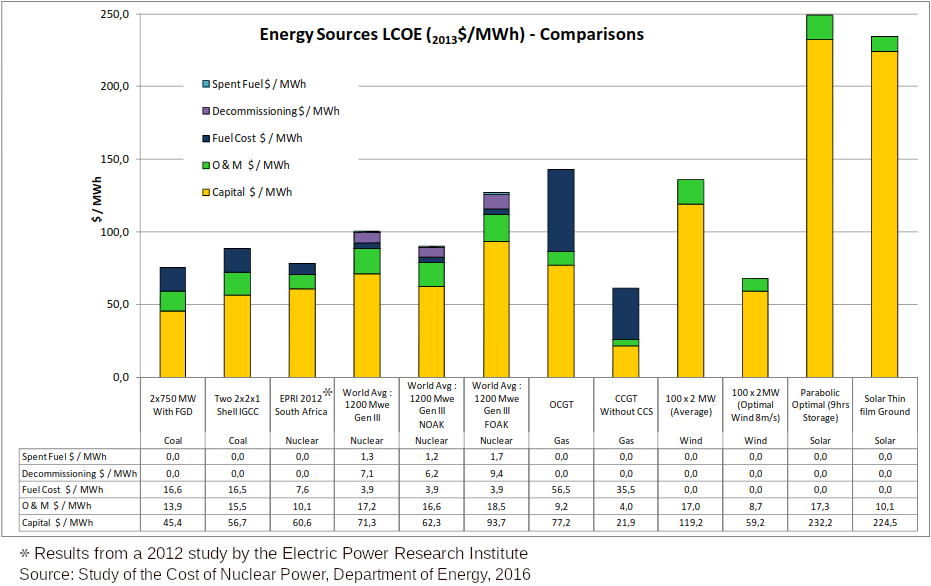

This was puzzling, since a study on the cost of nuclear power, commissioned by the government in 2016, found that third-generation nuclear power plants came in a little more expensive than coal, but cheaper than gas and wind, and half the price of solar power, as measured on what is called the levelised cost of energy (LCOE). The only exceptions cheaper than coal were closed-cycle gas turbines, which were cheapest, and wind power under optimal wind conditions, which does not exist.

The LCOE measure tries to evaluate the lifetime cost of lifetime energy production, from initial build to fuel use and maintenance to decommissioning. Despite its ambitious nature, an LCOE calculation has significant shortcomings, however. It does not consider quality in its formulation. Sometimes, the cheapest option is not the best option, as anyone shopping in a discount store knows, and as we can see by comparing polluting coal-fired power stations to slightly more expensive nuclear power plants.

More importantly, it does not measure power availability matching to the demand profile. In South Africa, demand peaks in the early evening, between 5pm and 8pm. Solar power availability, by contrast, peaks around lunchtime and produces nothing before 7am or after 6pm (as measured in August). LCOE does not factor in this cost, whether it is addressed by backup power sources or power storage solutions. It also does not account for grid integration, or the cost of acquiring vast tracts of land for solar or wind farms.

Even when measured on the basis of LCOE, which favours renewables, nuclear energy looks quite affordable. The draft IRP update published in 2018 “acknowledges the role of nuclear in the energy mix and calls for a thorough investigation of the implications of nuclear energy, including its costs; financing options; institutional arrangements; safety; environmental costs and benefits; localisation and employment opportunities; and uranium-enrichment and fuel-fabrication possibilities”.

Despite all this, the IRP does not actually plan for any new nuclear build by 2030, instead opting for 4.7GWe of hydro and 20 GWe of solar and wind power, to complement 34GWe of coal and 12GWe of gas-fired power plants.

This mix makes little sense. As we’ve seen, nuclear energy is cost-competitive. It also has tremendous other advantages. In a previous column, we saw how extraordinarily safe it is. It is the safest form of energy known to humanity, beating even hydro, wind and solar power.

Environmental Progress, an organisation advocating for “energy justice” that delivers a clean environment and cheap, reliable energy for all, has produced a fascinating list of statistics. Among them is that wind energy produces about the same greenhouse gas emissions as nuclear, but solar power produces four times more. Solar requires 450 times more land than nuclear energy. Wind requires 400 times more land. Solar requires 18 times, and wind 11 times, the construction materials of nuclear.

Nuclear produces reliable base-load power, and although newer-generation reactors can also ramp up and down fairly quickly, the ideal setup would have gas turbines for peaking power. Solar and wind are only available when the weather plays along. Solar can’t produce consistent baseload at all, while it peaks at the wrong time. The wind is better for baseload, since there’s always wind blowing somewhere, but it only produces whatever the weather deigns to deliver.

Denmark, which derives nearly half its electricity from wind, and can only do this because it can import or export electricity from neighbours to match demand, has the most expensive electricity in Europe. Germany, which is famously installing “green” energy and shutting down its nuclear plants, has the second-highest electricity price in Europe.

In supposedly green Germany, only 39% of the electricity supply is clean, and 61% is dirty. It hasn’t met any of its emission reduction targets and won’t do so any time soon. In neighbouring France, which gets most of its electricity from nuclear, 86% is clean and 14% is dirty.

Proponents of renewable energy point to the declining price of wind turbines and solar panels. But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. German electricity prices rose by 51% during its energy transition between 2006 and 2018, so French electricity now costs only 60% of what it costs in Germany. During California’s solar build-out between 2011 and 2017, electricity prices rose by 24%. In 2018, electricity prices in renewable-heavy California were 67% higher than the average in the rest of the United States. Denmark’s wind energy programme doubled its electricity prices since 1995.

In South Africa, one needs to look no further than page 100 of Eskom’s Integrated Annual Report to see the exact same effect. Despite the supposed competitiveness of renewable energy, power procured from renewable energy independent power produces (REIPPs) cost 20 times as much as nuclear power procured from Koeberg. Even coal-fired power cost more than three times as much as a nuclear power. Only gas turbines were more expensive than renewables, probably because, like real geniuses, Eskom is running them on diesel, not natural gas.

If Germany and California had invested all the money they invested into renewables into nuclear energy instead, they would have 100% clean energy by now. In Germany, it would even have been enough to convert its entire transport fleet to electric vehicles.

No nation has ever gone green using renewable energy. Two nations did go green, however: France and Sweden. In 2017, Sweden generated 95% of its energy from non-polluting, zero-carbon sources, of which about half came from hydro and the other half from nuclear. France generated 88% of its energy from non-polluting, zero-carbon sources, with the vast majority of that being nuclear energy.

Zambia is pinning its hopes for a reliable energy supply on nuclear power. Bolivia has inked a major deal with Rosatom to build a nuclear complex. The Russians are also building an atomic energy centre in Rwanda. Russia and China are competing to help Argentina expand its nuclear fleet. The Russians are also helping China to expand one of its own nuclear power plants. New nuclear power plants are under construction in China, Russia, Belarus, Finland, India, Japan, South Korea, Slovakia, the United Arab Emirates, Argentina, Pakistan, the US, France, Bangladesh, Turkey and the UK.

New UK prime minister Boris Johnson said: “It’s time for a nuclear renaissance.”

Let’s hope that Mantashe’s re-commitment to nuclear energy is reflected in the draft IRP to be tabled in September 2019. And as the previous draft emphasised, the more nuclear you build, the more cost-effective it becomes, so let’s build a decent-sized fleet and revive the country’s nuclear expertise and industry. A stable, reliable energy industry is critical to building industrial capacity and creating jobs.

Nuclear power isn’t just the best way; it is the only way South Africa can have energy that ticks all three boxes, of being reliable and clean and cheap, which is what is necessary to fuel the economic reconstruction the country so desperately needs. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider