South Africa’s “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) to the Paris Agreement avoids recognising the urgency of responding to climate change and the IRP 2018 follows suite. Even as government emphasises that poor people are most vulnerable to climate change, officials keep repeating that eliminating poverty and reducing inequality are its “over-riding priorities” – as if that justifies burning more coal.

South Africa is not alone. At Paris, the governments of almost every country in the world agreed on a dysfunctional climate regime. They agreed to hold global warming to “well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and to try to keep it under 1.5°. But they avoided creating any obligation to act as if they mean it and instead relied on each country’s voluntary “contribution” – they could not even make it a “commitment”. The sum of all NDC’s will come to 3° or 4°C warming.

In June this year, leading climate scientists warned that “cascading” climate feedbacks – where crossing one tipping point sets off the next – may be triggered at between 1.5° and 2°C warming above pre-industrial temperatures. This is runaway climate change leading to unliveable “hothouse earth” conditions. One such feedback concerns the melt of Arctic sea ice resulting in faster warming as the dark sea absorbs heat that the ice reflected outwards. That in turn will provoke faster melting of permafrost wetlands which will then release more carbon and methane into the atmosphere.

Warming is now at over 1°C above the 1850-1900 average. This is already dangerous climate change: people are experiencing extreme heat, drought, hurricanes and floods; and some critical tipping points may be tipped but we won’t know for certain until after the event.

The impacts at 1.5°C will be much more severe, particularly for the poorest half of the world’s people, and the impacts at 2°C exponentially more severe, as the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on 1.5°C, due out next week, will show. The collapse of agriculture is already threatened in some regions – notably in Africa – and the collapse of global fisheries from ocean warming and acidification, as well as industrial over-fishing, is in process.

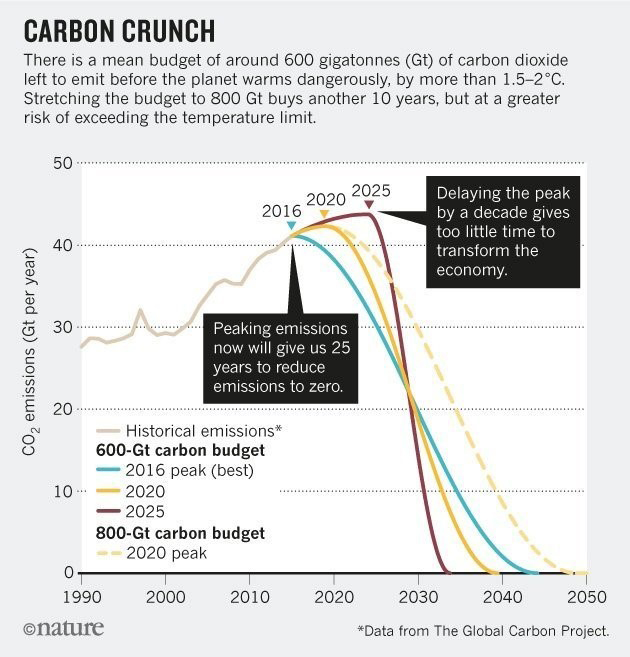

The IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5) showed that the global carbon budget for a one-in-two (50%) chance of avoiding 1.5°C is all but used up. Their calculations did not account for feedbacks. The budget for a slightly better two-in-three (66%) chance of avoiding 2°C is similarly depleted. If global emissions peak by 2020, they will need to decline to zero before 2040, as shown in the figure below taken from a paper by Stefan Rahmsdorf and Anders Leverman of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Berlin. This too, does not take account of feedbacks.

This means that all countries, including South Africa, have less than twenty years to get to zero. Effectively, there is no carbon budget left to share out. Hence, equity in terms of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ must now be pursued through financial and technology transfers. This may be considered as part payment of the climate debt owed by the rich world to the poor world. But it must also be remembered that there is a climate debt from rich to poor in Africa and, most notably, within South Africa. Finally, energy planning must be about a rapid transition from coal to renewables and it must be embedded in the larger conception of a just transition to a society that provides for all.

Carbon unlimited

IRP 2018 says it does not count the ‘externalised costs’ of carbon emissions because “the CO2 emissions constraint imposed during the technical modelling indirectly imposes the costs to CO2 from electricity generation”. In other words, they put a limit on how much CO2 can be emitted instead of costing the climate damage from burning coal to generate electricity. But the limit on CO2 emissions is not real. The IRP says “mind your head” when it has made the ceiling four metres high.

The IRP claims to have two approaches to imposing a carbon constraint. The first is to follow the ‘peak, plateau and decline’ (PPD) trajectory adopted by IRP 2010. The PPD has a wide range with an upper and a lower limit. IRP 2010 ignored the lower bound and took the upper limit to define its trajectory. IRP 2018 simply repeats this and so allows power sector emissions of 275 Mt CO2 a year through to 2035. The second approach is to allocate a carbon budget to the power sector for each decade. For 2021-2030, the budget is 2,750 Mt CO2 – that is, 275 Mt a year – the same as the upper PPD limit.

Eskom’s emissions in the year to March 2018 were 205 Mt CO2. Emissions from non-Eskom generators (mainly Sasol) add less than 10 Mt/y. So the IRP allows 60 Mt/y more than the sector emits at present for the whole decade of the 2020s. In this period, the IRP adds the remaining Medupi and Kusile units as well as two new privatised coal plants – Thabametsi and Khanyisa to be built and owned respectively by the Japanese Marubeni Corporation and the Saudi ACWA corporation. These plants are much more expensive than renewables so they add unnecessary costs and carbon emissions to the electricity system. At the same time, six of Eskom’s plants are scheduled for end-of-life closure by 2030. The IRP produced seven scenarios with various combinations of technology and most put emissions in 2030 at around 215 Mt.

Things are scarcely more challenging for the decade of the 2030s. Upper PPD keeps emissions at 275 Mt/y to 2035 and reduces emissions by 5 Mt each year thereafter. That brings it down to 250 Mt in 2040, still 35 Mt above current emissions. The carbon budget approach allows 1,800 Mt for the whole decade. None of the IRP scenarios come close to this limit so the ‘constraint’ is meaningless.

For the next decade, upper PPD starts at 243 Mt in 2041 and declines to 192 Mt in 2050 for an average of 217 Mt/y over the decade, which is no reduction on present emissions. Under the carbon budget approach, the IRP allows 920 Mt for the decade. Two scenarios exceed this limit but the “least cost” scenario comes in below the limit and hence also below the “carbon budget” scenarios.

The least cost scenario is the only one that does not place an arbitrary limit on how much renewable energy is built each year. So government can improve on its carbon budget simply by removing this limit. We should indeed spend more than least cost, but to further reduce emissions, not to increase them.

Thus, the carbon budget scenarios merely pretend to put a limit on carbon emissions. These scenarios retain the constraint on how much renewable energy can be built each year and introduce new nuclear plants, at a hefty cost premium, to meet the limit on emissions. This seems to be their real function – they keep nukes on the table.

The climate imperative is to reduce to zero emissions by 2040, not just for the power sector but for the whole economy, if we are to avoid making much of the earth unliveable within what might otherwise be the life-time of today’s youth. The IRP fritters the time away. It represents the refusal to recognise the real consequences of emissions from burning coal, oil and gas. It is a form of climate denial.

Health

The IRP hardly does better on local pollution impacts. It makes a stab at counting the ‘externalised costs’ of emissions of nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO2), mercury (Hg) and particulate matter (PM). It says, “These externality costs reflect the cost to society because of the activities of a third party (ie Eskom and other electricity generators) resulting in social, health, environmental degradation or other costs”. In other words, these numbers represent people dying prematurely or living with debilitating diseases caused by emissions. The IRP is, however, too discrete to tell us how many people’s lives are ruined or what value it puts on their lives.

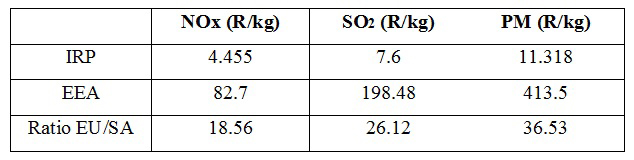

The table below shows the cost in rand per kilogram that the IRP attributes to each species of pollution and compares it with low end values (converted to rand) from the European Environment Agency. I have left out mercury because the IRP figure is wrong and it’s not clear if this is a typo or a blunder.

IRP local emission externality costs

The implication is that European lives are valued at between 18 times more (NOx) and 36 times more (PM) than a South African life. Comparisons of this sort are always invidious because the lives of the rich are given a higher value than the lives of the poor. But even if we allow for the fact that Europeans are 5.5 times richer than South Africans (GDP per person), the South African government still puts a very low value on the lives of its people.

The real costs to people are appalling as Mike Holland showed in a paper for groundWork. Emissions of just one species of pollution – fine particulate matter – from Eskom result in over 2,200 premature deaths every year. Tens of thousands more people are afflicted with asthma and bronchitis. Thousands are, or should be, admitted to hospital, many more suffer “restricted activity days” – days when they cannot function normally – and every year about a million working days are lost.

This costs the economy some R33-billion but the human costs are much higher and are not evenly distributed. As Holland observed, “air pollution most affects those whose underlying health condition is worst, and hence that any improvement in air quality will most benefit those who are most disadvantaged”.

The IRP externalities are only for emissions to air from power station stacks. They do not take account of the pollution of water and land from coal stockpiles, ash heaps and acid deposition. Nor do they take account of the massive impacts of the coal mines on air, water and land as well as on people’s health.

A rapid phase out of coal will immediately clean up the air and create the conditions for restoring earth. This is why the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change, reporting in 2015, said that “tackling climate change could be the greatest global health opportunity of this century”. Fixing the damage – rehabilitating not just mines but whole mining regions – would also require much work and should be conceived as an integral part of a just transition. DM

David Hallowes is a researcher at groundWork, an environmental justice organisation

Become an Insider

Become an Insider