WAY OF THE WARRIOR

Why men need to belong – from SA to Japan, from the battlefield to the playing field

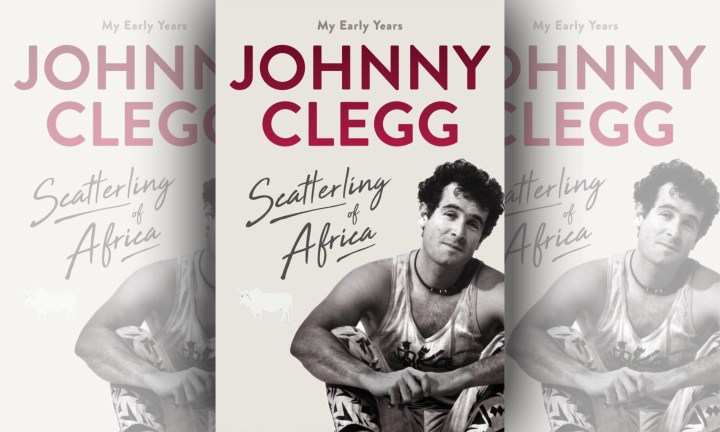

As Johnny Clegg’s just-published autobiography, ‘Scatterling of Africa’, reveals, men have a deep yearning to belong.

The notion of a man as “warrior” is one that would provoke considerable eye-rolling in some parts of the 21st century world with its more fluid interpretation of masculinity and its “uses”.

But as Johnny Clegg’s just-published autobiography, Scatterling of Africa, reveals, men have a deep yearning to belong. Whether it is as a football or rugby supporter, one of the “squad” or as part of an ibutho regiment.

While these codes varied from culture to culture, wrote Canadian author, academic and former politician Michael Ignatieff in 1999, “they seemed to exist in all cultures and their common features are among the oldest artifacts of human morality; from the Christian code of chivalry to Japanese Bushido, or ‘way of the warrior’, the strict code of the samurai, developed in feudal Japan and codified in the sixteenth century”.

As ethical systems, writes Ignatieff, these codes were primarily concerned with establishing the rules of combat between men and defining the “symptom of moral etiquette by which warriors judged themselves to be worthy of mutual respect”.

At best, within rigid boundaries of hierarchy, ritual and respect, boys and men can safely explore and learn to deal with the shadows within.

At worst, toxic masculinity fuels violence when disconnected from notions of “a greater good” or a larger body of like-minded men, brothers, comrades, brasse, brus.

What then to make of men and the need to belong to and be accepted by a group of other men? Especially what to make of all the fatherless sons in South Africa carried and cared for by their mothers.

What becomes of the lost boys?

Clegg was such a lost boy.

He regarded himself as fully Zulu in mind, body and soul and found great wisdom and guidance in some of the warrior codes between the men – the migrant workers from then-tribal lands – who had to learn to fight for every inch of liberty in apartheid Johannesburg.

Men, old and young, torn from family and familiar surroundings to shape a life in a city of diversity and danger.

Here the warrior code offered a reservoir of wisdom and strength, of how to flow with the water, but also stand your ground when you must. How to live with yourself inside a hostile system that views you as cheap labour, backward, tribal.

The culture, language, music and dance Clegg encountered on the rooftops of the Joburg flatlands and bleak hostels gave birth to him as a man.

“In many ways, the dance and its brotherhood was a male parent to me.

“Its male-centred warrior world engaged me, shaped parts of me and gave me many moments of deep happiness, even under the harshest conditions,” he recalls.

It was, he says, like “joining a gang”.

All young men, writes Clegg “must go through certain rites of passage, whether self-chosen or prescribed for them”.

Ignatieff, in his series of 1999 essays published as The Warrior’s Honour – Ethnic War and the Modern Conscience, writes of the “warrior’s code” that is expected in the theatre of war.

“Warrior’s honour implied an idea of war as moral theatre in which one displayed one’s manly virtues in public,” writes Ignatieff.

To fight with honour was to fight without fear, without hesitation, and, by implication, without duplicity.

Without duplicity.

“The codes acknowledged the moral paradox of combat: that those who fight each other bravely will be bound together in mutual respect; and that if they perish at each other’s hand, they will be brothers in death.”

The warrior’s honour “was both a code of belonging and an ethic of responsibility”. This encompassed who passed for a combatant and noncombatant in regions beset with conflict.

Where rag-tag soldiers and mercenaries are recruited as individuals or rogue groups and paid to kill in wars they stumble across, there is no code of honour. There, unrestrained toxic masculinity rages and results in gross violations of human rights.

These are the shallow codes that bind criminal gangs across the world – bankers, drug lords, the lot. While they claim brotherhood, they are loyal only to the codes of supply and demand. It is a duplicitous brotherhood.

The warrior code for the migrant worker in Johannesburg was deployed in a theatre of war and struggle, against not only poverty, but racism, violence and persistent state harassment.

The heart of a Zulu warrior, writes Clegg, must be “robust”.

“It is not bothered by changes in the world because he, the warrior, is a problem for the world. The world must deal with him and his will to make an impact on each day.”

The heart is where emotional conflicts embed themselves and the inshinga’s heart pounded “with the power to enforce his will”, said Clegg.

Clegg notes that he was challenged from time to time during his life “about the deep patrimonial aspect of the traditional male universe”.

His own close encounter had been with the migrant workers and it was their sense of the masculine self in the world he had been exposed to without restraint.

Apartheid had frozen rural communities into “ideological constructs”, remarks Clegg, and for a man at that time, “It was in your interests to maintain any power base in your own culture because when you retired, there was no pension or social security net, you were simply dumped back in the tribal rural area.”

Clegg, until his death in 2019, continued to perform his warrior dances alone in the garden, like a man working through his demons, facing them head-on.

Ignatieff, in an essay titled The Warrior’s Honour, recounts the story of Jean-Henri Dunant, a wealthy Swiss German who while travelling in northern Italy in 1859 watched the Battle of Solferino.

All day the armies of Emperor Napoleon III of France and Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria fought each other. Franz Joseph withdrew in defeat at dawn. In his A Memory of Solferino, says Ignatieff, Dunant set out what a battlefield looks like when the guns and explosions have quietened.

What he witnessed there, the dead, the dying and the wounded from both armies, was to change his life.

For most Europeans Solferino was a victory that helped to secure freedom for Italy from Austrian dominance. But for Dunant it was “a moral puzzle he was to struggle to decipher all of his life, and the neglect of the wounded a scandal that gives a lie to the myths of a nation’s gratitude to its soldiers”.

Like Florence Nightingale, Dunant, writes Ignatieff, “refused to accept that war was a matter for soldiers alone; as a civilian, he had strode into their moral sphere and insisted that what happened there was everyone’s business”.

At Waterloo, the common dead of both armies “were left to rot on the battlefield; their bones were gathered up by English contractors, shipped back to Britain, ground up, and sold as bonemeal and fertilizer”.

Because of Dunant’s work, by the time of his death in 1910 most countries had established national Red Cross societies.

Civil War nurse Clara Barton founded the US society, and Red Crescent societies were established in Muslim countries.

What Dunant understood was that international conventions governing behaviour during wartime had to draw on a “deeper moral source” between men – “the codes of a warrior’s honour”. He sought to marshal the forces of conscience of his time.

The war on South Africa by men, mostly young men, is evident in the shockingly high murder rate in this country and also the shredding of the social fabric of society that gender-based violence causes. The cost to children, women and other men is immeasurable. It holds us all back.

South African men are in crisis.

Somewhere the brotherhood has turned toxic and no longer offers young men tools to guide themselves or to aim for the stars, even if it is only a dream. The collective masculinity of the rural Zulu men Clegg encountered was cosmic in worldview.

We leave it to the White Zulu to sum it all up.

“At some time in their lives, everyone sees through the world and its big laughing confidence trick. When that happens a lot of folks think they are the only ones who can see the false passing parade and they become depressed and withdraw, not able to fully participate.

“It’s like the veil is lifted and reality becomes a conspiracy and a fraud in which deeply held values and sentiments are just a kind of currency used to hide the real rapacious and cunning activities of self-interested individuals mixed in with fickle fortune, ready to ambush you with quirks and challenges.

“A warrior not only sees through the trickster world, but actively engages it and says, Whatever your tricks, you will have to deal with me, for I am a problem for you and your great game, oh world! I am a warrior. I am unknowable, known only by my actions and the force of my will. In the end you will have to take account of me. I am not going away and my story will be told. I am the thorn in your foot that can only be removed by means of another thorn.” DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Profound insights

In the Zulu men of the gold mines Clegg found one of the world’s pre-eminent warrior cultures. It made for excellent lyrics and music, but for me some the best songs were about the displaced people, like Mama Tshabalala and Third World Man.

Thank you, Marianne, concise summation of the thrust of his book. It’s a book for men, about men but, alas, I suspect few will read it.

Thank you Marianne for another of your incisive reviews. Wahbie Long’s Nation on the Couch refers to alienation as a backdrop to the violence in South Africa. Johnny Clegg’s warrior is not dis-similar to heroes in the blockbuster genre that includes Star Wars and the Lion King. For the modern man, an appropriate rites-of-passage experience can have profoundly beneficial influences. Jungian interpreter, James Hollis addresses this issue in his book, Under Saturn’s Shadow, The Wounding and Healing of Men and the importance of the Hero’s Journey in the transition to authentic manhood. There are men’s groups in South Africa that can provide these experiences safely, including the Mankind Project.

Jeremy Hazell