/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/label-Editorial.jpg)

Jeff Bezos, the billionaire who purchased The Washington Post for $250-million in 2013, has overseen multiple rounds of layoffs and now the elimination of roughly a third of its entire workforce. More than 300 jobs were eliminated in a single blow to the storied outlet. Shuttering foreign bureaus, the sports desk, the books section and large portions of its metropolitan reporting, the paper’s former executive editor, Martin Baron, described it as a case of near-instant, self-inflicted brand destruction.

Its publisher and CEO, Will Lewis, resigned days later. Chaos, fear and speculation abound in what feels like the death spiral of one of the most important journalism institutions in the United States. The columnists and star reporters who had made the Post indispensable through the first Trump era have largely already departed. The newspaper that broke the Watergate scandal and published the Pentagon Papers is now reduced to what media analysts call an exhibit of attempts to smother democracy in broad daylight.

This may look like a distant US melodrama. It is not. The destruction of The Washington Post carries lessons of existential urgency for the South African media landscape and for every newsroom working for and in the pursuit of public interest.

When the owner is the threat

The first and most searing lesson is this: the greatest danger to a free press may not come from the state, but from the billionaire in the boardroom.

The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times are all thriving relative to many other news outlets. Admittedly, The Washington Post has failed to navigate the great disruption, losing $100-million in the most recent financial year. That size operating loss is a significant market challenge for any media organisation and would require consistent efforts in driving leadership development, innovation and a clear editorial strategy. Challenging but not impossible.

If losing $100-million sounds like a lot, we do need some perspective when Amazon paid $40-million to produce (and another $35-million to promote) a failed documentary about Melania Trump, Bezos’ new wife wore a $5-million dress to a wedding that cost an estimated $25-million, and they sail around the world in a $500-million superyacht.

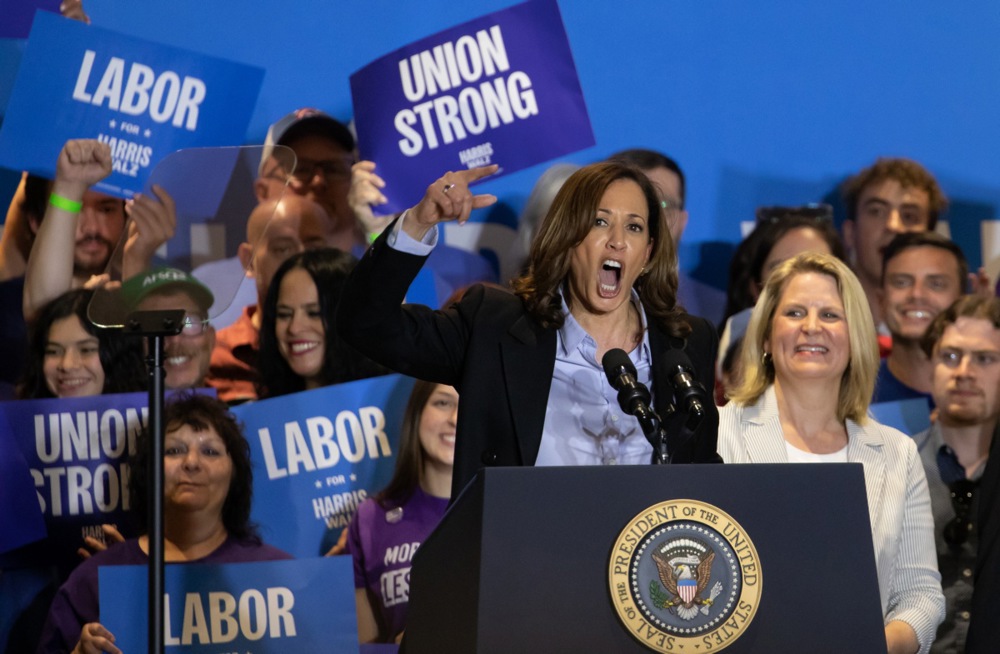

Instead, the evidence suggests Bezos chose to neutralise the paper as an act of political appeasement. Since late 2024, when the Post’s editorial team was blocked from endorsing Kamala Harris in the presidential race, the trajectory has been consistently downward: subscriber flight, editorial capitulation, and now mass layoffs.

Strikingly, Bezos was silent when the FBI raided Post reporter Hannah Natanson’s home, seizing documents and devices in an unprecedented attack on press freedom. Natanson covers the federal government and has been working on a national security leak investigation.

The pattern is unmistakable, and it appears the Post has been sacrificed to protect the broader commercial empire of Bezos, with Amazon Web Services’ multibillion-dollar Pentagon cloud contracts and other business interests at risk because of the Post’s potential to cause headaches for the Trump administration.

South Africans have seen a version of this. In one of the most egregious examples, the saga of Independent Media under Sekunjalo Investments demonstrated how concentrated private ownership can distort editorial direction and weaponise newsrooms for political and business agendas. But the US case adds a new dimension: a billionaire who does not even need the newspaper for profit can simply let it wither as a gesture of political loyalty to an authoritarian-leaning regime.

Previous approaches to buy The Washington Post were rebuked, indicating that the mission is now to gut and maim an organisation capable of causing trouble for the Trump regime.

This is the new playbook. Across the United States, the Ellison family (of Oracle fame and fortune) now controls CBS, once a bastion of courageous broadcast journalism, which is being softened into a vehicle that handles the current administration with kid gloves. Elon Musk’s X platform has become a vector for uncontrolled disinformation, and TikTok’s US operations are now governed by a consortium of Trump-aligned interests where keywords like “Epstein” are blocked from search results.

When oligarchs accumulate media alongside commercial empires that depend on regulatory favour, editorial independence is actively traded away.

This is calculated. They understand why it is important to gut these institutions. The question is: Do we have the bravery to support them when we can, before the billionaires and private equity owners raid?

Independence is linked to sustainability

The second lesson is that financial independence is a precondition for editorial independence. Relying on a single owner or a single revenue stream is a structural vulnerability masquerading as stability.

When Bezos bought the Post for $250-million, it was heralded as salvation. A tech visionary with deep pockets would modernise a legacy institution. And for a time, he did invest. The Post’s newsroom grew to more than 1,000 people and, under Baron’s stewardship, reclaimed much of its power. But single-owner dependency meant that when the owner’s political calculus changed, the entire institution was put at risk.

And others may be next. If Twitter can be bought for $44-billion and controlled as needed, then The New York Times, with a market cap of $11-billion, may also be on a billionaire’s shopping list with chopping board intentions.

The 2025 RSF World Press Freedom Index rightly warns that the economic indicator for press freedom is at an unprecedented low globally. The challenges around sustainability make our most important newsrooms vulnerable to takeovers and gutting from the inside.

The lesson is not that corporate money is inherently corrupting. As a recent Sanef essay argued, journalism has always been intertwined with commercial forces, and the integrity of reporting is measured by the courage of practitioners, not the purity of the funding ledger.

The lesson is that concentration is the enemy. When one person’s political convenience can override the editorial mission of a 148-year-old institution, something has gone catastrophically wrong with the ownership structure.

Journalism as a public good

The third and deepest lesson concerns how societies conceptualise and value what journalism is.

The Washington Post was treated as a private asset — something an individual could buy, reshape, and ultimately cannibalise based on personal interest. This is the logic of the market applied to a public function. The result is what we now witness: one of the most important watchdog institutions in the world’s most powerful democracy disabled at the precise moment it is most needed.

Journalism that serves democracy by investigating corruption and providing critical information that citizens need to navigate their lives cannot survive on market forces alone. It is a public good in the economist’s sense: its benefits are diffuse, its costs are concentrated, and it will always be underprovided by the market. The market does a terrible job of creating a sufficient supply of public goods.

Every citizen benefits when investigative reporting exposes malfeasance, but few are willing to pay the contributions that sustain it. This is why we fund courts, universities, green spaces and public health systems through collective means. The case for treating serious journalism with the same logic is now irrefutable.

This does not necessarily mean state-funded media. South Africans know better than most the dangers of a captured public broadcaster. It means creating mixed-funding ecosystems that can include public media funds governed at arm’s length from government, philanthropic endowments. The more we can fund public interest journalism as a public good through incentives, rebates and tax deductions, the more we can insulate the industry from needing to be saved and then controlled by wealthy owners.

Read more: We can save journalism in South Africa, but only if we recognise its role

The motto and the moment

The Washington Post’s motto was aspirational. But aspiration without structure, without diversified funding, without governance that protects the editorial mission from the whims of owners and the pressures of authoritarian regimes, is just a slogan.

South Africa, with its constitutional guarantee of press freedom and its hard-won tradition of investigative journalism, has both the reason and the opportunity to build something more durable.

The gutting of the Post is not just an American tragedy. It is a global warning. Whether we heed it will determine whether, in our own democracy, the lights stay on. DM

Styli Charalambous is the CEO and co-founder of Daily Maverick.

The Washington Post’s downward trajectory began in late 2024, when the newspaper’s editorial team was blocked from endorsing Kamala Harris in the US presidential race. (Photo: Rebecca Droke / EPA)

The Washington Post’s downward trajectory began in late 2024, when the newspaper’s editorial team was blocked from endorsing Kamala Harris in the US presidential race. (Photo: Rebecca Droke / EPA)