The light was beginning to thin along a stretch of road in Alexandria in the Eastern Cape when a teenage boy in wire-frame “spectacles” lifted his face toward the camera.

That unguarded instant would travel far beyond that winter afternoon, to a wall of the National Portrait Gallery in London, and appearing in subways and on billboards as one of the standout images of this year’s Taylor Wessing Portrait Prize.

/file/attachments/orphans/Pic2WilliamSheepskinTheFarmhandsSon_993726.jpg)

For Cape Town photographer William Sheepskin (29), the journey that led to that moment feels almost unreal.

Sheepskin was drawn to Boshoek, a small farming area near Alexandria, where his father was born.

“I spent most of my teenage years in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, so South African heritage is something I didn’t really grow up with. My dad is from the area where I made this portrait, a tiny farming valley called Boshoek, and that connection felt important to me.

“I wanted to spend time out there and try to understand what my childhood might have looked like if my dad had never left the farm. It’s hard to imagine, especially because that way of life doesn’t quite exist there any more, or at least, that’s what I thought.”

/file/attachments/orphans/Pic5SelfPortrait_666347.jpg)

For two weeks in June 2024, he wandered through fields and along gravel roads, searching for traces of his father’s boyhood to which he could connect. Each day he returned with photos that felt incomplete.

“I mostly had photos of cows and fields. I wondered if I was learning anything at all. I did, but at the same time not,” says Sheepskin.

Then came the afternoon when everything shifted. Three carefree boys stood at the roadside, wire toys in hand, with their faces lit by the setting sun.

One of them was 14-year-old Vuyisanani Sinqoto, who wore a pair of “spectacles” fashioned from wire that immediately drew Sheepskin’s attention. The photo would be titled The Farmhand's Son.

“It was strange for them, and for me, to stop and ask if I could make their portrait,” he says with a quiet laugh. “It’s the only time I’ve photographed someone under 18 without a parent present. But the moment felt special. You can see it in his expression: authentic, unselfconscious, full of presence and quiet authority. That’s what made the image stand out.”

/file/attachments/orphans/Pic1IMG_8769_450210.jpg)

He took a single photograph and drove on. Only weeks later, when the National Portrait Gallery expressed interest in the photograph, did he realise his mistake: he had photographed a minor without parental permission — and he had no way of contacting the family.

“So I got in the car and drove 15 hours from Cape Town to the Eastern Cape,” he says. “I had three prints with me, two for them and one to give to someone at the exhibition. I thought: I’ve come this far; I’m not turning around.”

Wild goose chase

In Alexandria, he chose the dirt road, the slow road, and for half an hour saw no one. “I thought, this is a wild goose chase.”

Then, improbably, the first person he encountered was a farmer who recognised the boy. “He said, ‘His dad works with me.’”

The farmer radioed for Fundile Sinqoto, Vuyisanani’s father, who arrived on a tractor, surprised and cautious.

“I explained that I had the chance to exhibit the portrait as part of the Taylor Wessing prize [awarded by the National Portrait Gallery],” says Sheepskin. “There were 50 photographers in the exhibition, so the odds of winning were slim. And even if I did, any prize wouldn’t be mine alone.”

“Vuyisanani is my only child,” says Sinqoto with pride in his voice. “I have always been so proud of him. But seeing that picture, it was something else. The way William took the photo makes my heart happy. To think my son’s face was seen overseas, it’s a feeling I can’t even explain.”

He admits he was not immediately convinced to sign the release form. He says he had many questions, but Sheepskin convinced him he had no ill intentions.

“You don’t just let anyone take a photo of your child,” he says. “At first, I thought, what does this man want? What is he going to do with the picture? But William explained himself nicely. He told me he had no bad intentions, that he just loved the moment. And you know, sometimes you can see when someone is being honest. So I agreed.”

/file/attachments/orphans/Pic4AADB2FF3-49C4-47FA-BC3F-616E7E175630_865638.jpg)

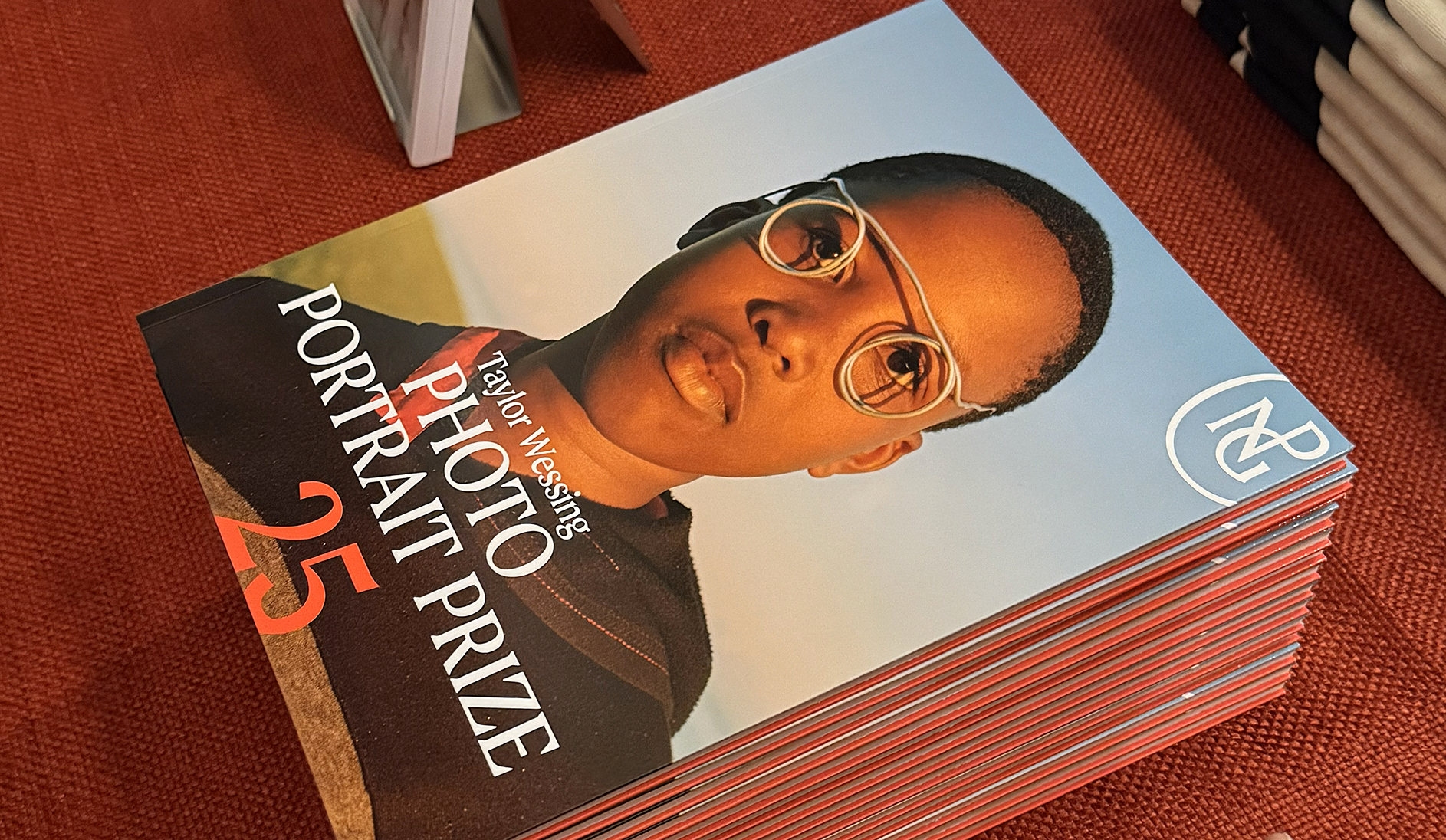

Although the photo did not win, the gallery selected it for the catalogue cover, and it featured prominently in the exhibition’s promotional materials.

Sheepskin, who got his first camera when he was just 11 years old, said it was a special moment to see his picture next to one taken by the British photographer Cecil Beaton.

“Sharing a billboard with him is special in its own way,” he says. “I have an enormous sense of gratitude for everything that has come from this picture. I make so many photographs that mean a lot to me, but most of them never get seen.

“The fact that this one has reached so many people, that it’s out in the world instead of sitting on my hard drive, that feels like a reward in itself.” DM

The photo that William Sheepskin took of Vuyisanani Sinqoto appears on the cover of the National Portrait Gallery catalogue. (Photo: William Sheepskin)

The photo that William Sheepskin took of Vuyisanani Sinqoto appears on the cover of the National Portrait Gallery catalogue. (Photo: William Sheepskin)