In a city that never stands still, Angela Makholwa (50) is a multi-talented professional who embodies the energy, hustle and complexity of Johannesburg. As one of the first black women to break into South Africa’s crime fiction scene, she has carved out a space that reflects both the grit and vibrancy of the city, capturing its complexities on every page.

As a wife and mother of two, Makholwa has built her life in Joburg over decades, her personal and professional worlds unfolding alongside the city’s evolution.

She has always found herself drawn to Joburg’s restless heartbeat. The Thembisa-born author lived briefly in the Eastern Cape while studying journalism at Rhodes University. Once she completed her studies, she briefly lived in Buccleuch and Northriding before finally settling in Midrand, where she has spent most of her adult life.

/file/attachments/orphans/WFD_1817_595091.jpg)

Makholwa’s home reflects her roots and success. Family portraits hang throughout, grounding the space in warmth and belonging. Cowhide mats and African-inspired décor speak to her heritage, while a lively bar area and shelves brimming with books reveal her love of hospitality and storytelling.

She’s published six novels, and her writing is rooted in recognisable Joburg life. Her business ventures mirror its dynamism, and her personal life unfolds against the backdrop of a metropolis that hardly sleeps.

Making her mark

Makholwa stepped into the literary world with her debut novel Red Ink, which was inspired by her encounters with notorious serial rapist and killer Moses Sithole. The story highlights Joburg’s nuances, such as the perks of young-adult life in a growing city, alongside the rampant crime and violence that persist to this day.

The book’s success took her by surprise. “I felt like nobody was going to read this because there was no market for it. I hadn’t seen South African crime fiction, let alone many black fiction writers, at the time. So I was writing it for myself, to be honest. It was selfish and silly.”

Yet readers responded. Red Ink was adapted into a Showmax series in 2024. “One of the things I was most mindful of was the need to honour the victim in whatever small way… That was important to me,” she reflects.

Another of her works, The 30th Candle, which explores similar themes, was adapted into the film Love, Sex & 30 Candles, which premiered on Netflix in 2023.

“They’re expressive, vulnerable, ambitious and flawed. It’s a far cry from days when African women were portrayed as silent or one-dimensional. Now, we’re finally seeing the full spectrum of what it means to be human.”

Black women were rarely granted narrative interiority in many earlier literary traditions shaped by colonial discourse. In Makholwa’s fiction, Joburg’s women resist this pattern.

“They’re expressive, vulnerable, ambitious and flawed. It’s a far cry from days when African women were portrayed as silent or one-dimensional. Now, we’re finally seeing the full spectrum of what it means to be human,” she says.

/file/attachments/orphans/WFD_1789_472691.jpg)

Her stories are more than entertainment; they’re social commentaries exploring themes of blackness, womanhood and the relentless pulse of Johannesburg.

“I’ve always been entrepreneurial,” says the CEO of Britespark Communications and non-executive director at Lipco Law For All.

She moves between boardrooms and book launches with the agility that Joburg demands. Running a PR company means Makholwa helps companies and institutions figure out how to tell their stories to the public, whether through media coverage, digital campaigns or large-scale events.

It’s storytelling of a different kind: less fictional villain, more reputation management. Her work at legal insurance company Lipco Law For All prioritises mediation over courtroom drama. Instead of pushing disputes straight into expensive, emotionally draining litigation, the organisation works to resolve most cases around a table, through conversation, negotiation and structured compromise.

The person behind the profile

Beneath the hustle, Makholwa comes across as a genuine people person. While she thrives in Joburg’s creative spaces, such as local book clubs, her favourite “hat” is that of motherhood: “I know it sounds like a PR response, but my kids make me so happy.”

Despite the grandeur of her home, the atmosphere is unmistakably relaxed and welcoming. By late afternoon, the comforting aroma of dinner begins to fill the house, a reminder that, for all her accolades, Makholwa is happiest in the heart of her home among her family.

Unlike those who “just wake up and decide they want to write a novel”, Makholwa approached her debut novel with discipline and intention. Drawing on her journalism background, she enrolled in a novel writing course before tackling Red Ink.

“How do I keep you engaged? How do I make you turn the page?” she muses, showing her deliberate effort behind her storytelling.

“People take shortcuts these days, especially with the rise in things like ChatGPT,” she says, urging the next generation to develop thick skin and seek out opportunities beyond narrow titles. Resilience has become one of Makholwa’s survival skills in Johannesburg.

Jozi’s shadows

Makholwa’s fascination with Jozi’s darkness goes beyond her love of crime fiction; it’s personal. The process of writing her debut novel was fraught, from unsettling prison visits to meet Sithole to the ethical dilemma of giving a voice to a psychopathic killer.

Sithole would lure his victims to lonely, quiet spaces on the false pretence of work opportunities, before assaulting and murdering them. Makholwa wrote to Sithole a few years after his last prison sentence, hoping to write a journalistic piece that would show his perspective.

Makholwa thought she was being prank-called when she received a phone call from Sithole roughly five to seven years after she first tried to make contact. She was no longer a practising journalist and could hardly remember writing the letter. Still, Sithole’s eagerness to have a book written about him piqued her interest, and she decided to pay him a visit at Kgosi Mampuru II Prison in Pretoria.

Read more: The wide appeal of Angela Makholwa

/file/attachments/orphans/WFD_1795_507845.jpg)

This project proved to be more difficult than Makholwa expected. She couldn’t take anything into the prison, which meant she had to memorise Sithole’s words during interviews before she could access her writing tools. Sithole also developed a slight obsession with Makholwa. He would write her love letters and poetry, which creeped her out. To date, Sithole has routinely called Makholwa to wish her a happy birthday every year.

Makholwa began to get cold feet while working on this project when Sithole started contradicting himself. He initially confessed to his crimes during their meetings, blaming it on past traumas and a difficult upbringing. Makholwa became annoyed when he later claimed not to have committed the murders, showing disregard for his victims.

“It’s probably naive to think that you don’t have a level of social responsibility as a writer. It’s nice to say ‘I just write what I like’, which I used to say, but in the end, a reader could be somebody who needs that hope, or who has been a victim.”

After a heated argument, Sithole forbade Makholwa from writing the novel. “I spent so much time gathering all this information. I wasn’t about to just let it go, and he couldn’t just tell me what to do,” she said.

After some thought, she decided to fictionalise the events into a novel, so as not to let the time invested and information collected go to waste.

‘Abusers have multiplied’

Her novels don’t shy away from the city’s harsh realities.

“It’s probably naive to think that you don’t have a level of social responsibility as a writer. It’s nice to say ‘I just write what I like’, which I used to say, but in the end, a reader could be somebody who needs that hope, or who has been a victim.”

Makholwa laments the rise in gender-based violence since her first novel was published in 2007, noting that what was once rare has become disturbingly common. “At that time, it was just [Sithole]. And look at that. He’s multiplied in the home, multiplied on the street; he’s multiplied everywhere. So what does it say about our current society?”

While the documented incidence of gender-based violence has increased in recent years, Makholwa observes that this apparent rise is, in part, a reflection of progress. Under apartheid and in earlier eras, the experience of marginalised communities, particularly black people and women, was often rendered invisible, unrecorded or dismissed by official systems.

As a result, many cases of assault and murder likely went unacknowledged. In post-apartheid South Africa, the not-perfect but more rigorous documentation and recognition of these injustices, though sobering, signal a society slowly beginning to account for and confront the realities faced by those previously excluded from the historical record.

Makhlolwa acknowledges that Johannesburg remains vastly unequal, yet she urges its residents not to lose sight of the strides made.

“We take it for granted, but the city’s growth is visible everywhere. Sometimes, when these small shopping centres spring up, I wonder, ‘Do we really need another one?’. Then the next day, the parking lot fills up, and it shows how Joburg’s progress is real and widely shared.”

While it’s easy to dwell on the city’s challenges, she points to the remarkable “upward mobility of black people” as evidence of genuine progress, a testament to the city’s evolution.

“I would definitely rather live in contemporary South Africa’s Johannesburg, with all its flaws,” suggesting that there is much to celebrate, despite its imperfections. DM

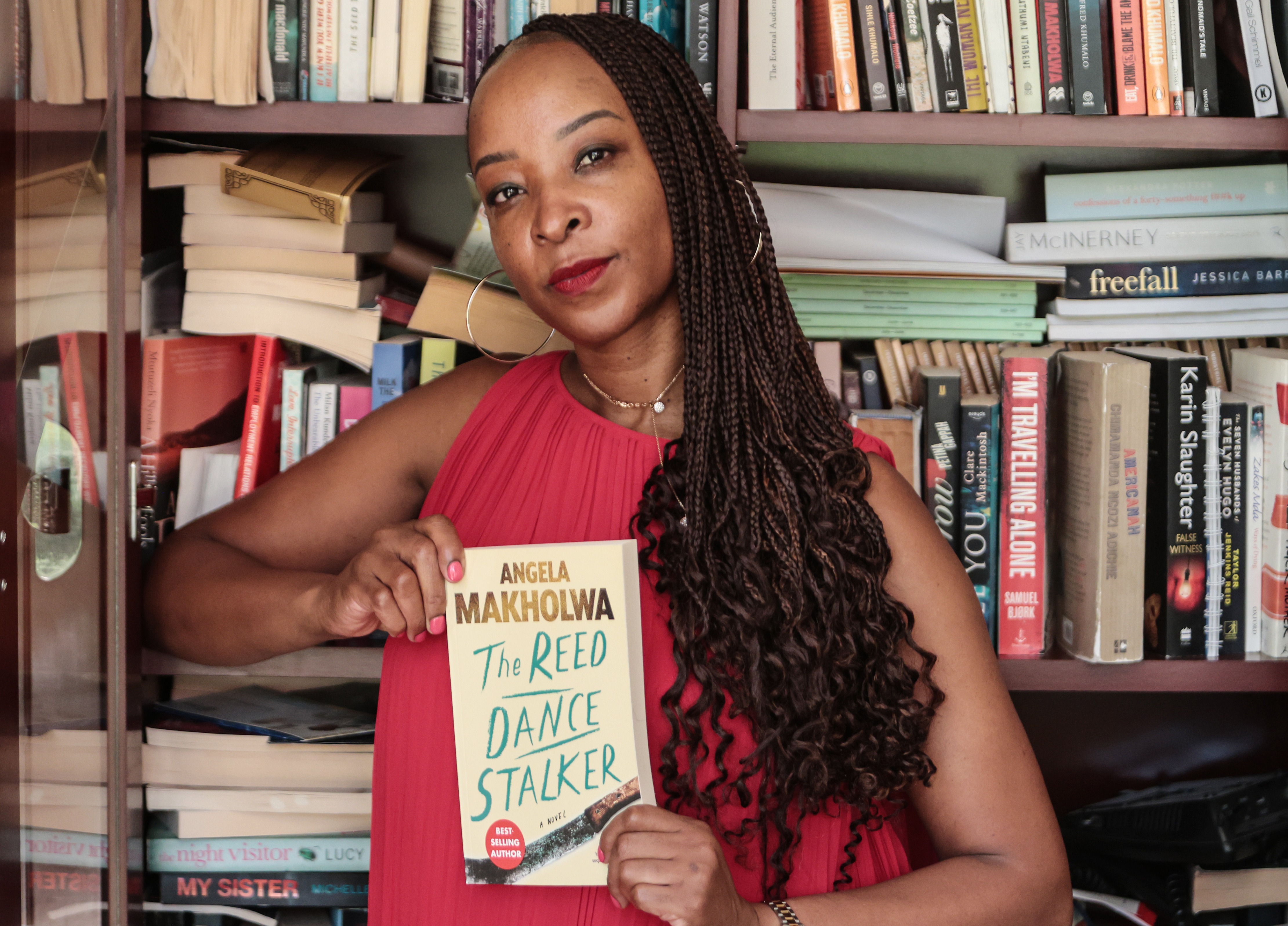

Angela Makholwa is a best-selling author and one of the first black writers to write crime fiction in South Africa. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)

Angela Makholwa is a best-selling author and one of the first black writers to write crime fiction in South Africa. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)