/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/label-analysis-2.jpg)

Like much of the rest of the world, South Africans, including the government, would have joined the audience at Davos, Switzerland, in loudly applauding Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney’s declaration on Tuesday that the time had come to stop appeasing global bullies like US President Donald Trump.

The annual meeting of the World Economic Forum at Davos had been dominated by Trump’s threat to take Greenland by force from Denmark — a threat which, if executed, would probably destroy Nato and implode the Western alliance.

However, in his speech at Davos on Wednesday, Trump walked back from his threat to use military force to take Greenland — but did not abandon his ambition to seize it somehow, presumably by economic coercion.

/file/attachments/orphans/2257422380_187373.jpg)

On Tuesday, Carney said it was time to stop pretending that a rules-based international order, with the US at its apex, still existed. That “nice story” was ending and being replaced by “a brutal reality where geopolitics among the great powers is not subject to any constraints.

“Great powers have begun using economic integration as weapons. Tariffs as leverage. Financial infrastructure as coercion. Supply chains as vulnerabilities to be exploited. You cannot ‘live within the lie’ of mutual benefit through integration when integration becomes the source of your subordination,” said Carney.

“The multilateral institutions on which middle powers have relied — the WTO [World Trade Organization], the UN, the COP [Conference of the Parties] — the very architecture of collective problem solving, are under threat.

“It seems that every day we’re reminded that we live in an era of great power rivalry,” said Carney. “That the rules-based order is fading. That the strong can do what they can, and the weak must suffer what they must.”

Read more: Canada’s Davos wake-up call for honesty rather than compliance

This state of affairs was presented as the inevitable, natural logic of international relations reasserting itself. “And faced with this logic, there is a strong tendency for countries to go along to get along. To accommodate. To avoid trouble. To hope that compliance will buy safety.”

Countries, he noted, were now competing among themselves to avoid being targeted, and many countries were drawing the same conclusions — that they must “develop greater strategic autonomy: in energy, food, critical minerals, in finance and supply chains”.

This was understandable. “When the rules no longer protect you, you must protect yourself.” But this was leading to a “world of fortresses” which would be “poorer, more fragile and less sustainable.

“But … other countries, particularly middle powers like Canada, are not powerless. They have the capacity to build a new order that embodies our values, like respect for human rights, sustainable development, solidarity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of states,” Carney insisted.

He invited other middle powers to join Canada in building this new world order.

BRICS and the Global South

Could South Africa play a role in Carney’s new order of middle powers? The South African government — the ANC in particular — has always railed against the post-war international order created by the US and other Western powers, which Carney and others now see evaporating. Presumably, though, Pretoria does not much like what it sees taking the place of that order, a world where might is unambiguously right.

The ANC’s counter to the Western order has largely been to join and then to help expand BRICS — the Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa bloc, which has become BRICS+ with the addition of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Indonesia, the United Arab Emirates and maybe Saudi Arabia, although the latter seems to be hedging its bets.

BRICS has also admitted Belarus, Bolivia, Cuba, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Uganda, and Uzbekistan as “BRICS partners”, enjoying some benefits of membership as a possible stepping stone to full membership. In theory, BRICS could keep expanding, possibly becoming a fairly powerful bloc of non-Western states.

That is a critical point. BRICS countries often refer to the organisation as a bloc representing the Global South, a catch-phrase for developing and emerging states. An important question, though, is whether a bloc which includes two great military powers, China and Russia, at its core, can be regarded as representing the Global South, or rather as speaking for developing and emerging states as a counterweight to the Global North — the developed states.

That anomaly creates problems for South Africa, which might perhaps have been avoided. Many — certainly in the West — see BRICS as a support club for Russia and China rather than as the genuinely non-aligned and objective organisation it purports to be. And the risks of expanding membership have been brought home to South Africa over the last week as Iran’s participation in the joint naval exercise Will for Peace, conducted from Simon’s Town, angered the US and caused a rift in the South African government.

Read more: Ramaphosa should fire Motshekga and all top officers involved in Iran fiasco, experts say

The South African National Defence Force, possibly in an effort to sneak Iran in via the back door, wrongly portrayed this as an exercise of the BRICS+ countries without the endorsement of its partner, the Department of International Relations and Cooperation.

/file/attachments/2986/navy2769_181267.jpg)

Need for tactical flexibility

Would South Africa be better off throwing its weight behind the club of middle powers Carney seems to have in mind, even if he has not precisely defined it? He did suggest these powers should respect human rights, among other values, which would be a good thing.

Yet Carney has also made clear over the last few weeks that in the turmoil succeeding the post-war order, he believes expedience can be in order. As he emphasised in his Davos speech, Canada recently signed a strategic partnership with China — not the greatest exponent of human rights — which was clearly intended to send a strong message to the White House that if it doesn’t want to be friends, Ottawa can go elsewhere.

But this tactical expedience does not entangle Canada as much as SA is entangled by its open-ended membership of BRICS+.

Read more: G20 South Africa goes post-Trump as middle powers signal fresh path

As Carney pointed out, Canada is diversifying its global relations, signing a dozen trade and security deals on four continents in six months, and also, “to help solve global problems, we are pursuing variable geometry — in other words, different coalitions for different issues based on common values and interests”.

That sort of tactical flexibility might be something SA could emulate.

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-2239338729_504074.jpg)

If we return to Carney’s central message, that it is time for middle powers to stop appeasing Trump and to stand up to him, it is clearly easier for Canada to do that than for South Africa. Canada’s economy was ranked ninth in the world in 2024 with a GDP of about US$2.243-trillion, while SA ranked 40th with a GDP of about $400-billion.

We have probably not seen the last of Trump’s hostility to Canada. At Davos, he berated Carney for Canada’s ingratitude for the security protection he said the US gives its neighbour and added, “Canada lives because of the United States.”

Notwithstanding the hazards of defying Trump, South Africa should seriously consider signing up in some form for Carney’s project. Could that be worse than staying the course with a BRICS bloc that will probably only get more problematic as it expands, and which Trump, incidentally, has already threatened to hit with punitive tariffs? DM

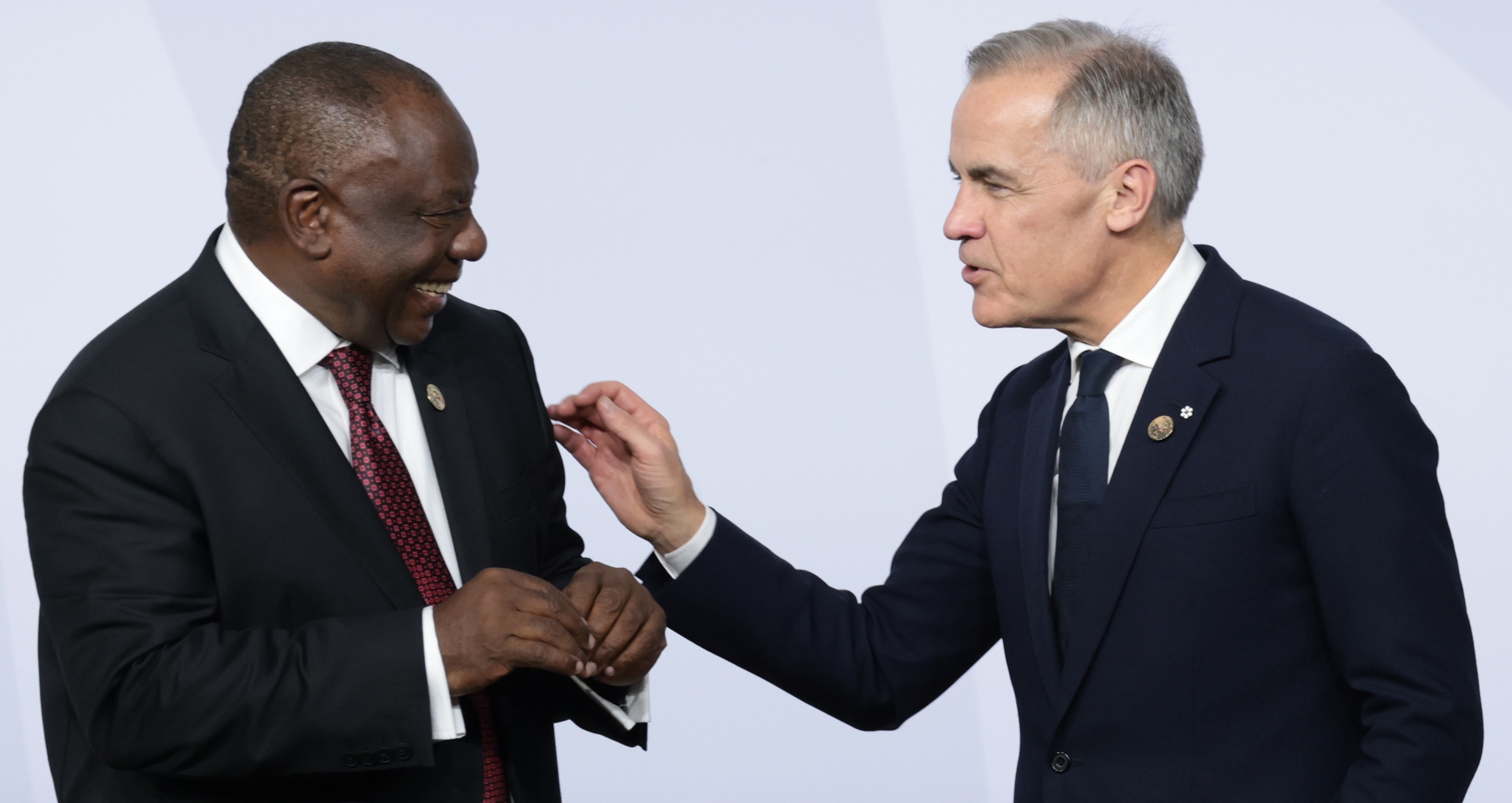

File photo of South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa and Canada's Prime Minister Mark Carney talk during a family photo event, on the first day of the G20 Leaders' Summit at the Nasrec Expo Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa, 22 November 2025. World leaders are gathering in South Africa, the host of this year's G20 Leaders' Summit on 22 and 23 November 2025, to discuss the global economy, development and financing. (EPA/YVES HERMAN / POOL)

File photo of South Africa's President Cyril Ramaphosa and Canada's Prime Minister Mark Carney talk during a family photo event, on the first day of the G20 Leaders' Summit at the Nasrec Expo Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa, 22 November 2025. World leaders are gathering in South Africa, the host of this year's G20 Leaders' Summit on 22 and 23 November 2025, to discuss the global economy, development and financing. (EPA/YVES HERMAN / POOL)