In what can only be described as hard-hitting investigative journalism, I ask Mpho Boshego if her fictional story about a young, beautiful diplomat in Belgium has anything at all to do with the fact that she had been a young, beautiful diplomat in Belgium.

Turns out, I was onto something.

In 2007, Boshego was a young official in the Department of Foreign Affairs. She’d done the training, the six-month stretch that turns you into someone who can live out of a suitcase and speak in policy sentences. Then the posting came through: Brussels. She was thrilled.

Being the sort of person who believes that books hold the answers to almost everything, Boshego did what any self-respecting reader would do. She went straight to the bookstore to find novels on diplomatic life. The grand total of these books was zero. A few months into the posting, she realised the problem was simple: the story she wanted to read did not exist because no one had written it yet. Then a Toni Morrison line landed like a dare: if there’s a story you want to read and you can’t find it, you must write it yourself.

“I wrote that on a piece of paper. I kept it in my wallet for, I think, maybe two years,” she says.

At first, she thought it would be her own experiences on the page: the culture shocks, the new city, the travelling. But the work quickly slid into fiction.

“I started writing a story about three women in diplomacy: an ambassador, a young diplomat, and a spouse. I wanted to imagine what that might be.”

Imagination took over and before long she had a manuscript. She sent it out, excited. A publisher responded with interest and conditions: exclusivity, no discussions with others while they considered it. They liked the story, but it needed work. They wanted time for editorial feedback.

Panicked

And then, just as it all became real, Boshego panicked.

“At the time, I think I was 27, 28,” she says. “I had not found my voice. What if people read this and think it’s my story? And the thought of that was embarrassing.”

So she shelved it. Life took over. The manuscript became one of those objects you carry through the years, proof of who you were before you learned how to stand behind your own sentences. It took a long time to return. Fifteen years.

“Between that time and now so much has changed. I got married, had two children, got divorced. But I also started feeling that I had a right to occupy space in the world. I stepped into feeling that I was worthy of telling a story.” She says it simply, it’s the difference between knowing how to write and believing you’re allowed to. “It’s okay. And if people judge it, that’s all right.”

In 2023, she went back to the manuscript. This time, she stayed. The pages felt different. Or maybe she did.

“As I got into Mbali’s head, the other characters became side characters to Mbali’s story.”

She had started writing in 2007. A full manuscript existed by 2009. The version that became Diplomatic Ties emerged in 2023.

At its centre is Mbali Langa, a young woman raised in Mamelodi, in a home crowded not just with relatives, but with instability. Her father has long since disappeared. Her mother lives with untreated mental illness. A grandmother holds the household together. An uncle drinks. There is love, but there is also pressure, the kind that quietly settles on the shoulders of the one child who might make it out. Mbali is clever, disciplined and ambitious. She trains as a diplomat, carrying both her own dreams and those of the women who raised her. But upward mobility is never clean. Early in her career she becomes entangled with a powerful minister, a relationship that is as transactional as it is emotional. Money begins to move. So does power.

Survivalism

Boshego tells me that survivalism was an important theme for her.

“I wanted to write a story about someone’s life that is also quite layered,” she says. “Very beautiful, but also messy. I wanted to show that even when your life is messy, even when you make the wrong choices, as we sometimes do, you’re still worthy.”

That insistence on worthiness sits at the heart of the novel.

Diplomatic Ties is, on the surface, a professional coming-of-age story. But beneath that, it is a study in risk management. The constant calculation of what you can afford to do when you know how easily everything can disappear.

“I wanted to create a character who is smart, ambitious, young – with the whole world open to her,” she says. “She had to come from great hardship and find glamour. I wanted to show how she lives in this duality.”

Mbali carries the promise of tomorrow and the precarity of today in the same body. She also carries her family: the grandmother who steadied her, the mother who faltered, the unspoken expectation that she will be the one who makes it out and brings something back.

“How do you navigate that,” Boshego asks, “especially when you’re young, especially when you are thrown into systems and situations where phrases like ‘career limiting’ are used and you have not found your voice yet?”

When we start talking about books, really talking about them, the conversation shifts. I can feel it. The air changes. The room brightens. Somewhere in my head an orchestra starts playing. This is our language. This is where we meet.

And, inevitably, the love of books slides into the politics of them. We talk about the ones that have stayed with us. The African Writers Series. Contemporary novels from across the continent that bend form and voice in daring ways. Books that are layered and propulsive at the same time. Work that refuses to choose between pleasure and depth.

Pace, texture and movement

And it is there, in that shared admiration, that her own project makes sense. She did not want to write something heavy simply to be taken seriously. She wanted pace, texture and movement.

“I wanted to write something… a page-turner, quick, but still kind of rich,” she says. “People don’t have the time like we used to. You need to respect the readers. They’re not dumb.”

What she is resisting is not seriousness. It is the assumption that seriousness must be slow. That difficulty equals depth. That accessibility signals compromise. We have both seen the quiet hierarchy that hovers over SA fiction. The books that travel well abroad. The ones labelled literary before they are even read. Accessibility treated as suspect, as if pleasure requires apology.

But the books we are naming between us do not obey that rule. They are rigorous and readable. Glamorous and political. Layered and alive. Why should SA fiction have to justify itself through pain in order to be taken seriously?

It can be cosmopolitan. It can be romantic. It can be deliciously readable. And still ask difficult questions. DM

Joy Watson is the Book Editor at Large at Daily Maverick

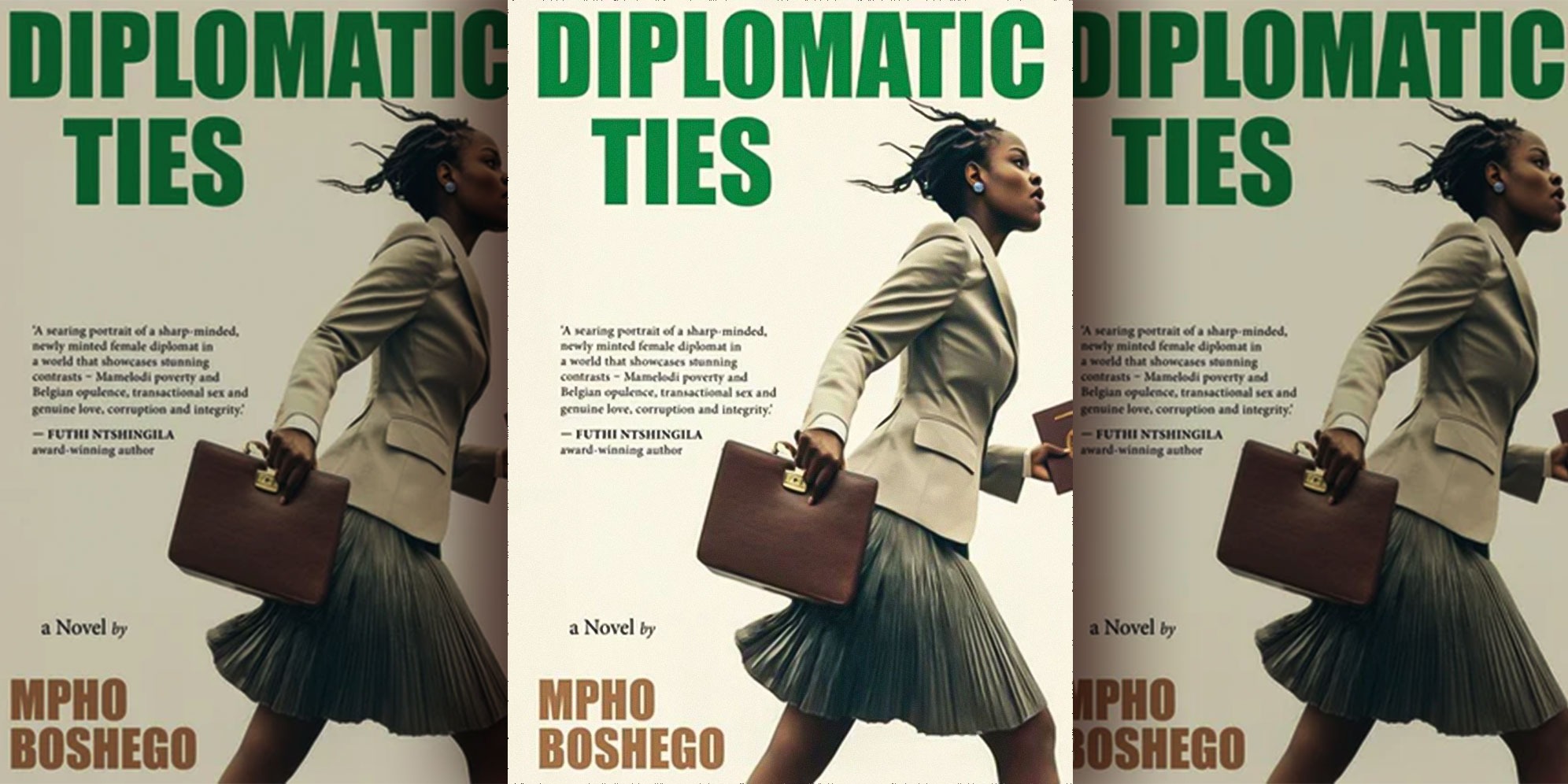

Illustrative Image: Diplomatic ties by Mpho Boshego. (Image Sourced / Exclusive Books)

Illustrative Image: Diplomatic ties by Mpho Boshego. (Image Sourced / Exclusive Books)