The Reverend Jesse Jackson passed away on 17 February at the age of 84. He was a charismatic religious figure who transformed himself into the leading public voice for African American dreams, hopes and aspirations in the years following the assassination of the Reverend Martin Luther King Jnr. Beyond his role in the civil rights revolution, he was the first African American to make a real race of it as a presidential candidate in two separate electoral cycles. And his electoral efforts cracked open the door that Barack Obama walked through a generation later.

Speaking of the late civil rights leader, former president Obama said of him: “From organising boycotts and sit-ins, to registering millions of voters, to advocating for freedom and democracy around the world, he was relentless in his belief that we are all children of God, deserving of dignity and respect.” Jackson was supremely comfortable in joining together religious feelings with down-to-Earth political efforts.

At the apex of Jackson’s prominence and social and political influence in America, he was a frequent presence on television, as well as at protests and demonstrations across the nation, speaking strongly as a champion for the urgent necessity for government action on civil rights – and for social justice globally.

At a moment of deep national crisis as civil disorder had erupted after the death of King in 1968, Jackson, who had also been at the Lorraine Motel, the site of King’s assassination, became a national voice for restraint and nonviolence. More recently, when civil disorder broke out after the police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, Jackson had again urged calm – as well as measures to address injustice and inequality.

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-171119899_610899.jpg)

In the years following the King assassination, Jackson began searching for a broader stage for his energies as he engaged in efforts aimed at Middle East peacemaking and prisoner releases, as well as the growing international movement against apartheid in South Africa.

For example, he helped gain the release of a captured US Navy pilot from Syria; the release of 48 Cuban and Cuban-American prisoners in Cuba; and bringing home citizens from the UK, France and other countries who had been held as “human shields” by Saddam Hussein in Kuwait and Iraq in 1990. There were also his negotiations to gain the release of US soldiers held hostage in Kosovo; and the negotiations for the release of journalists in Liberia who were working on a documentary for British television.

Over the years, Jackson also became something of a regular in the company of presidents and foreign leaders. For example, he found himself in South Africa on the day of Nelson Mandela’s release from incarceration, and he was at Mandela’s first public address at the Cape Town Parade on that same day.

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-185046089_424948.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-945879636_623197.jpg)

Years later, in 2013, Jackson received South African national honours in recognition for his efforts on behalf of bringing apartheid to an end. When this writer met Jackson – now an old lion from many battles – he had walked through the lobby of his Pretoria hotel as waiters, desk clerks and hotel guests alike cheered him on, shouting out to him, “Hiya, Rev” or “Run, Jesse, Run” – the latter the signature chant of his two US presidential runs.

Although Jackson was an ordained Baptist minister, he never served as a resident minister in his own church, preferring the calling of the wider stage of civil rights activism. He was born in Greenville, South Carolina, but his base was Chicago, Illinois, where his social activism and pro-poor advocacy efforts through organisations he had been an integral part of, People United to Support Humanity and Operation Breadbasket, were similarly based.

Jackson had that instinctive, fluid grace of a natural athlete and his was a commanding presence wherever he appeared. His electrifying oratory drew deeply upon the rhetorical style and cadences of the Southern Black churches he knew so well. In a speech or sermon, he would begin slowly, with an almost conversational tone, and his phrases would gradually – but inexorably – build to a crescendo that could leave some in his audiences in tears.

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-480960811_658218.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-466702260_272409.jpg)

To be scrupulously fair, during his decades-long career, Jackson could simultaneously be one of the most galvanising and inspiring as well as divisive figures in American public life. In truth, no one was ever neutral about the Reverend Jesse Jackson. (At one crucial moment in his 1984 presidential effort, he casually insulted New York City and its residents as Hymie-town. The uproar may have scuppered his chances of winning the New York State presidential primary and it contributed to a widening rift between black and Jewish communities only partially healed during Obama’s own presidential campaigns.)

Jackson’s biographer, Marshall Frady, has written that by 1988: “He [Jackson] had become by then an altogether singular figure in the nation’s life, that was obvious. But who was he really? What did he mean? What had happened to that original promise? Too, there undeniably is, for many, a certain blare and swagger about his persona – a reaction that may owe not a little to that same racial tension, actually.

“But at the same time, largely unrealised, un-noted, is the enormous popular admiration and even enthusiasm about him that’s still out there across the reaches of the country, massive in the black community but in no negligible measure in white quarters as well, on campuses, in the environmental movement…

“It is not so much that he is a quintessentially American figure, as that his has been an extraordinary American pilgrimage in its themes…”

“The most iconic photographs from Jackson’s life – the ones everyone remembers – seem to have been connected to the life and death of his mentor/colleague, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. There is the one where King and Jackson are on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee where they had gone to support a dustman’s strike – but then there is dreadful succeeding frame where Jackson is pointing to where the assassin, James Earl Ray, had been lying wait to shoot Martin Luther King…”

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-456515029_791157.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-2227949127_548660.jpg)

In speaking of Jackson’s two runs for the Democratic presidential nomination, the late Kenneth Walker, the prize-winning African American print and broadcast journalist who had lived for years in South Africa, once told this writer: “Reverend Jackson has spent a lifetime in giving voice to the voiceless and power to the powerless in ways that reverberate through history. Barack Obama’s election is just one example. Reverend Jackson’s own presidential campaigns reformed party nominating rules like winner-take-all. Perhaps more importantly, he first identified a Rainbow Coalition of voters that has Republicans wondering if they can ever win another election.”

It is fascinating to recognise that both Jackson and Obama had sharpened and refined their political nous in the sharp elbows, rough and tumble of Chicago’s politics, even though both their origins were distant from that city. Jackson had been the son of a poor single mother in the South, while Obama had come a far distance from Honolulu, Hawaii and Jakarta, Indonesia. If Jesse Jackson ultimately failed to gain the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination, two decades later, Obama would succeed, drawing upon some of the same ideas at the core of Jackson’s energies.

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-2215323903_860498.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-2167476569_780318.jpg)

Thinking deeper into Jackson’s political meaning, a long-time American academic resident in South Africa once told this writer: “Jesse has always had more substance than the media give him credit for, preferring to use him as a jester and a foil for ‘serious’ politicians. His high-flying rhetorical style both played into and against this characterisation, as his serious speeches were serious and memorable indeed, and I would rate him as amongst the greatest political orators in English in the 20th century; yep, right up there with King, Kennedy, Roosevelt, Churchill.”

Of his political life, Jackson told me: “So I said, ‘somebody needs to run to challenge this system’. We couldn’t get our agenda onto the agenda – for worker rights, a two-state Middle East solution, free Mandela and all the rest… And somewhere out of that dusty road, there came a cry, ‘Run, Jesse, run!’ Without any kind of preparation or planning, we decided to go for it. To remove the psychological barrier, I decided to go for it. That we could compete at that level; that was beyond our imagination. We’d never gone in that zone before.”

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-173951764_130480.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-1354526361_379781.jpg)

As to whether race would always be central to the American ethos, Jackson mused: “Race should not vanish, racism should vanish. People go to school together, they’re on political tickets together… It takes time, but that day is coming. It is supremacy’s notion that you have some kind of inside track that is the problem.

“We are 50 years after the King speech, 150 after abolition, 350 years after slavery. We have that in our ‘DNA’. We were enslaved longer than we have been free. We see morning is coming, but it has been a deep, dark night; but those who have never experienced it, think it was always sunlight.”

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-1159435921_972337.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-941434962_954627.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/GettyImages-101567187_386990.jpg)

Thinking about all that Jackson meant to America and Americans, I wrote: “Listening to Jesse Jackson, one could not help but hear the biblical cadence in his language and in his thinking; in the way he described the big issues in starkly moral terms and in his insistence on never stopping in the work of carrying some big, heavy stones up a very big hill. But another biblical metaphor comes to mind as well, in an echo of his mentor’s own 1968 speech during that ill-fated visit to Memphis.

“King had said then: ‘He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.’ At least metaphorically, Jackson too is of a kind of American Moses. He’s been brought to the very edge of his secular Promised Land; he had been allowed to gaze upon it and to long for it; but he was fated to never quite cross over that last stretch of land from where he was now to where America can go.”

Years later, we can stand by that judgment. DM

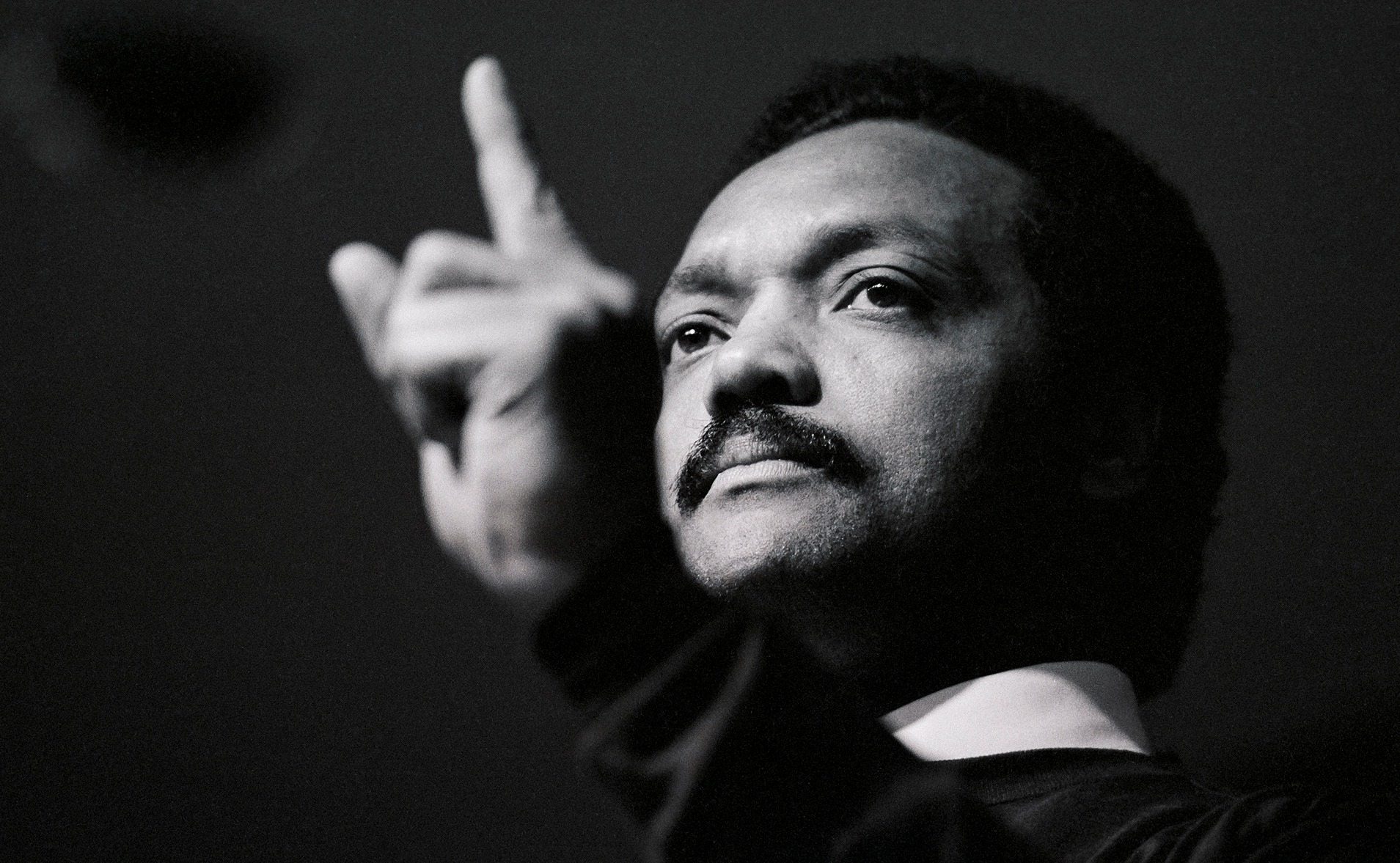

Reverend Jesse Jackson gives a speech during his Democratic presidential run in New Orleans, 1984. (Photo: Joe McNally / Getty Images).

Reverend Jesse Jackson gives a speech during his Democratic presidential run in New Orleans, 1984. (Photo: Joe McNally / Getty Images).