Imagine dropping to one knee and, instead of a sparkling rock, presenting your beloved with a rare vintage vinyl, a hand-carved wooden spoon or a particularly sentimental piece of sea glass. If the idea feels absurd, you are a testament to the most successful psychological operation of the 20th century.

While engagement traditions trace back to ancient Egypt and Rome, the diamond’s monopoly on the human heart is a modern invention. De Beers spent nearly a century engineering a campaign to equate diamonds with love, but as we enter 2026, this eternal connection is fraying.

The natural diamond industry is in a precarious position following three years of systematic erosion that has gutted margins across the mining, manufacturing and retail sectors.

/file/attachments/2988/Screenshot2026-02-13at144451_256743.png)

Graph: Paul Zimnisky Diamond Analytics

According to De Beers Group’s fourth quarter 2025 production report, its rough diamond production decreased by 35% to 3.8 million carats, primarily because of the maintenance shutdowns at diamond mines in Botswana.

The Department of Mineral and Petroleum Resources in South Africa reported that the diamond sector’s sales value plummeted by 19.2% in 2024, driven by lower prices and sales mass volumes.

The culprit of this value erosion is the lab-grown diamond (LGD), a disruptor natural diamond stakeholders are now desperately rebranding. Buyers are choosing these stones for their identical look at a fraction of the cost, while younger consumers specifically value them as a sustainable, conflict-free alternative to the human rights and land disruption issues associated with traditional mining.

Read more: The allure of a lab-grown diamond, as the sparkle of mined stones fades

Diamonds without forever

While LGDs are welcomed as ethical alternatives, the natural diamond industry is trying to strip away the polite terminology.

“I’m talking about very different products here. They’re not the same. It’s something that’s produced in a microwave room,” said Eirik Waerness, senior vice-president and chief economist at De Beers, referencing the production method of lab-grown diamonds.

“If you’re presented [with them] by the retailers as the same product, you could question why one should be so much more expensive than the other. [Natural diamonds] are unique products. If you’re talking about the size of [natural] diamonds, there’s not very many of them in the world.”

/file/attachments/2988/Screenshot2026-02-13at140318_596304.png)

This sentiment is echoed across the industry. Elton Escrivão, commercial director at Angola National Diamond Company (Endiama), was even more blunt about the synthetic threat. “The level of carbon emissions coming from synthetic diamonds is huge because they are not made in a lab. They are [made in] factories. I don’t even think they are lab-grown diamonds. They are factory-made diamonds,” he said.

Lab-grown stones are created using advanced high pressure, high temperature (HPHT) or chemical vapour deposition (CVD) technology in controlled laboratory or specialised manufacturing facilities. They are generally considered to have a smaller environmental footprint than mined diamonds, with less land disruption and habitat damage, though production is energy intensive and its impact depends on whether renewable power is used.

Nosiphiwo Mzamo, CEO of South Africa’s State Diamond Trader, argued that LGDs should not even be called diamonds and questioned the use of the carat measurement. Both mined and lab-grown diamonds are weighed using the same standard, where one carat equals 0.2g.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/cultured-diamond.jpg)

A new pitch for old stones

Realising that the “eternal love” narrative is failing to compete with LGDs that are up to 98% cheaper, the natural diamond sector is pivoting to a value over volume strategy. The new pitch is that buying a natural diamond is an act of social responsibility.

“Synthetics are cheap markets. People don’t understand what diamonds do for them and for the developing countries,” Naseem Banu Lahri, MD of Lucara Diamond Botswana, said. “Every human being in Botswana is a product of the diamond industry. Why would you deprive a country of value if that’s what it’s doing to the people of the country?”

Read more: Botswana’s mining cadastre reveals hydrocarbon scramble in iconic Kalahari game reserve

Data from Botswana mining company Debswana supports this narrative of nation-building. In its 2024 social impact report, the company notes that through diamond revenues, Botswana’s fortunes turned from one of the 10 poorest countries in the world in 1966 to an upper middle-income economy, with literacy rates jumping from 30% in 1967 to 90% in 2024.

“I see a diamond every single day when I see the roads, when I see the hospitals, when I see the schools, when I see all the positive impact that those stones are having on our community,” Escrivão said, noting that Endiama spent more than R1.9-billion ($120-million) on social responsibility initiatives in Angola last year alone.

Industry changes and upturn

While the marketing changes, the structural foundations of the industry are undergoing a reorganisation. De Beers, once the undisputed hegemon of the sector, is seeing its influence wane as Anglo American prepares to complete the sale of its 85% stake.

Read more: Anglo still favours De Beers sale, IPO option could include JSE primary listing

De Beers’ hold on the rough diamond market will keep slipping as the firm slashes its production and narrows its network of authorised buyers. This receding influence has created a strategic opening for mining nations to seize the reins through local beneficiation, which keeps the lucrative cutting and polishing work within their own borders rather than outsourcing the final sparkle to factories overseas.

“I think we have reached the baseline where we are now about to make the turn,” Mzamo said, adding that the industry is seeing an uptick in interest for bigger diamonds above two carats.

“In any industry, you’re going through a peak and a trough. We’ve reached the bottom, and I do believe out of this bottom here, we’re definitely seeing lights,” Lahri said. “It’s through the collaboration of producer countries and seeing how we market diamonds differently compared to where they were before.”

Will ‘scarcity’ lose its shine?

The question remains whether this strategic reframing will be enough to lure back a younger, budget-conscious consumer.

Waerness remains cautiously optimistic, suggesting the cycle may have finally turned. “If you have low prices for a while, demand will go up. But it’s fair to say that I think we are relatively close to the bottom in terms of prices,” he said.

According to Escrivão, the industry simply has no choice but to succeed in its rebrand. “We are 100% confident that we will have a brighter natural diamond industry, because we cannot afford to fail, right? We are too big to fail,” he said.

While you could technically propose with a piece of sea glass, the industry is banking on buyers embracing a different type of value creation. Whether consumers prioritise the legacy of a billion-year-old stone or the immediate health of their bank balance will determine if this famous carbon structure retains its crown. DM

Correction: An earlier version of this article had the incorrect spelling of Zimnisky in the graph attribution. (Updated 19 Feb 2026).

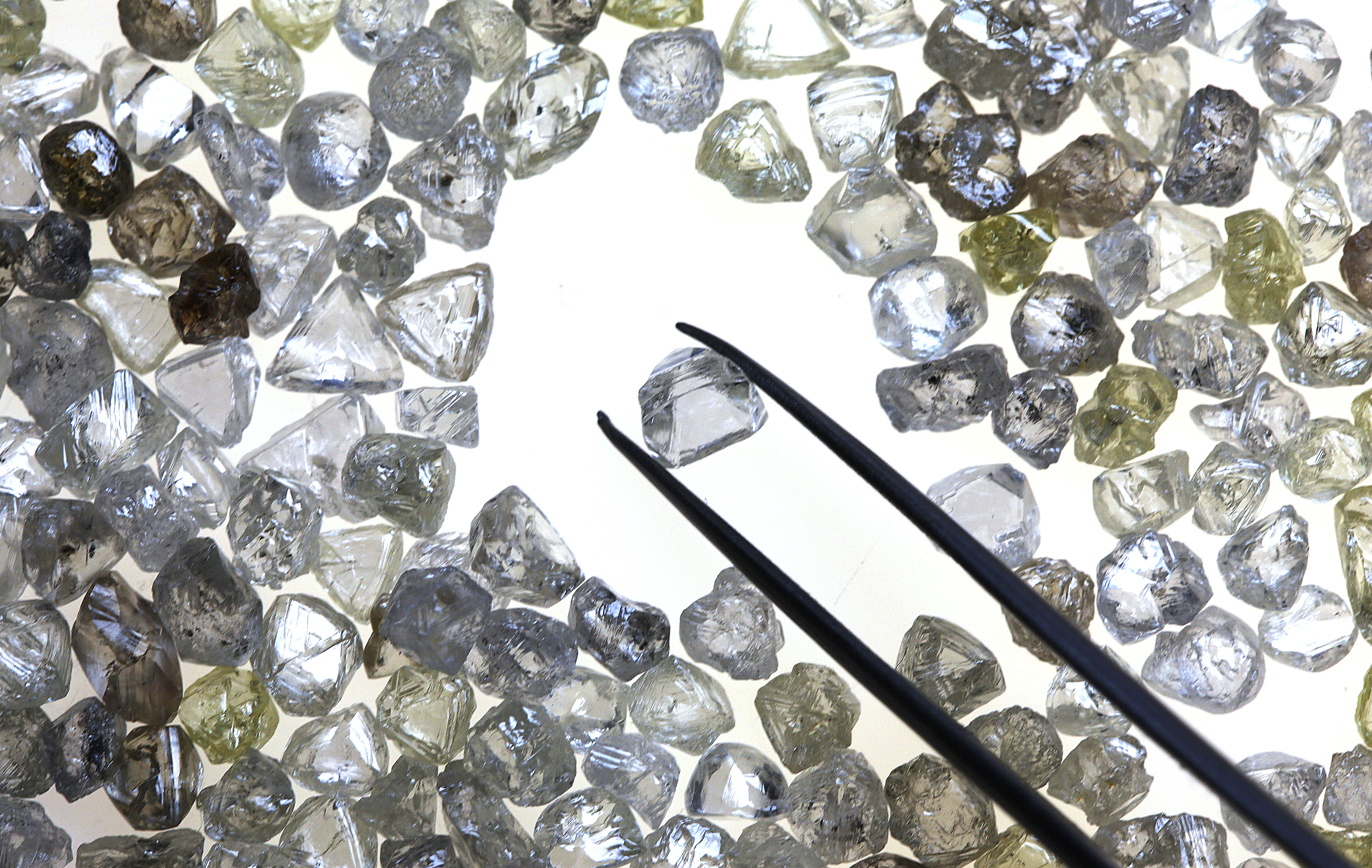

Uncut natural diamonds at a De Beers facility in Gaborone, Botswana. (Photo: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg)

Uncut natural diamonds at a De Beers facility in Gaborone, Botswana. (Photo: Chris Ratcliffe/Bloomberg)