Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema came into office in 2021 after pulling off a surprise election victory against the incumbent Edgar Lungu, despite Lungu’s many undemocratic efforts to cling to power, including imprisoning Hichilema for treason. Five years later, on 13 August this year, Hichilema, himself now the incumbent, will try to fend off challenges to his own re-election.

He has introduced many reforms, both economic and political, which would be imperilled if he were defeated. His political opponents say he should be, having “done more harm than good”, as Emmanuel Mwamba, who served as Lungu’s High Commissioner (ambassador) to South Africa, recently posted on Facebook.

He claimed Hichilema had borrowed more and engaged in more corruption than Lungu, given away national assets like Mopani Copper Mine and “destroyed democracy” through his attacks on the opposition.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/h_57118988.jpg)

Hichilema, nicknamed “HH”, shrugs off such criticism and says he has no fear that his many reforms will be reversed by his political opponents as he is confident the majority of Zambians will again vote for him, because he has done what he promised to do in 2021 when he was campaigning for election for the first time.

In particular, his government has put 2.3 million children back in school with its policy of free education up to grade 12. He was delivering the keynote address to the African Mining Indaba in Cape Town this week, as well as briefing journalists there.

“So who wants to reverse free education?” he asked, adding that his government was now moving to legalise free education so that if anyone wanted to reverse it, they would also have to reverse the law.

Hichilema said he had inherited a country with minus 2.8% economic growth, 22% inflation, heavy debt and considerable insecurity. His government had lifted growth to a predicted 6.4% this year; lowered inflation to single digits; restructured debt and put it on a downward trajectory; restored stability where there had been lawlessness, and revived agriculture, he said.

He also cited his energy reforms, allowing independent producers to generate electricity, which he said had prevented economic collapse when drought had slashed the output from hydroelectric power, Zambia’s main source of electricity.

“And so we believe on August 13th, 2026, there will be a decision by the Zambians based on our track record, a solid one… So we’re not worried about the elections.”

Hichilema said the reforms had sometimes been painful, and restructuring the debt he had inherited had taken too long. But Zambia was now bearing the fruits.

Copper revival

Copper remains by far the country’s biggest earner, as it has been for decades. And its value has rapidly risen over the last few years as it has been identified as a “critical mineral” vital for new industries.

Zambia’s copper production, though, declined under Lungu, in part because of protracted disputes between the government and private mining companies over ownership of mines.

Hichilema said his first reform was to end this damaging litigation by brokering talks among the litigants out of court. And so, for example, Konkola Copper Mines, which had been in liquidation, en route to expropriation, was now back in production.

This and other reforms had also revived other projects. Mopani Mine, which had been “comatose”, was now producing strongly again.

The government had revitalised the copper town of Luanshya which its residents had mostly abandoned because of the failure of the mine. After repairs to shaft 28, which had been dormant for 23 years, and to the town’s infrastructure, production would soon resume and people return, Hichilema said.

And Kalengwa mine, which had been out of commission for 47 years, was also now back in production.

Hichilema said his reforms had put Zambia on track to produce one million tons of copper this year, and three million a year in about a decade. Copper production alone had increased 12% in 2024, though dropping to an 8% increase in 2025 because of a few issues with old assets.

Overall he said mining companies had responded to the reforms by investing well over $12-billion since 2021.

Almost all the examples Hichilema cited, though, were in “brownfields” investments, upgrading old mines. He did not say much about new greenfield investment, apart from the Mingomba copper project, a major high-grade, underground copper-cobalt deposit which is being developed in a joint venture by the US mining firm KoBold Metals, and ZCCM-Investment Holdings, on behalf of the government of Zambia.

He also noted that the Zambian government was doing a high-resolution geophysical survey of the whole country, now about 55% complete, which was helping to de-risk the exploration that was vital to keep mining alive.

This had already attracted the Canadian Ivanhoe mining company to secure 7,757km² of new exploration areas. Zambia had also strengthened mineral regulations and overall governance, which had been very weak.

Increasing local content

A mining investment analyst who requested anonymity said Hichilema was largely “re-hashing old stories”, and “keep in mind we are in a Zambian election year and he’s very weak on the Copperbelt which he probably needs to win”.

However, Paul Gait, group head of strategy at Anglo American, suggested the problem was beyond Hichilema’s control. He noted copper had been mined in Zambia for decades and so a lot of its mining projects had already been built and developed. Copper mining had largely then moved onto neighbouring DRC, which had higher grades of copper.

With the copper price now at around $13,000 a metric ton, that would probably eventually change, though he didn’t see it changing in the short term.

Hichilema also said Zambia was now negotiating with mining companies and legislating to increase local content, giving opportunities in mining to small and medium local suppliers and contractors.

Although some mining companies had initially thought this was intrusive, it was in fact inclusive and necessary to create a vested interest for locals in mining as an insurance policy against “expropriation intentions”.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/ISS-Today-pic-9.jpg)

He agreed with what mining houses were saying at the Mining Indaba that the old style of investing in Africa only for their own higher profits was gone. Only partnerships could deliver returns to all stakeholders.

The Zambian president said his political opponents argued that mining companies were not paying enough taxes. But in fact mining companies were paying much more into the treasury through increased revenues, derived not only from increased turnover, but also royalties and taxes. These were financing free education, for instance.

“You can’t get milk from a stone. You cannot… kill businesses by overtaxing them…You have to have a balance,” said Hichilema, a former businessman himself.

Future plans included scaling up beneficiation of minerals, he said, citing the $115-million upgrade of the Kansanshi S3 copper smelter. “Africa cannot continue exporting raw materials forever.”

His other plans include: formalising and supporting artisanal and small-scale mining, though he strongly emphasised it would have to be safe and legal; driving green mining and strong environmental protection; building regional value chains via the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement and the Lobito and Tazara corridors; and empowering women and youth through skills and entrepreneurship.

Hichilema strongly emphasised that there “will be no state demands for free carry in mines without a reasonable commercial engagement”. He also stressed that his government did not support expropriation of investment.

“If there’s an issue we dialogue rather than expropriate, which costs the business a lot, costs the economy a lot, including jobs.”

He also pointed out to potential investors that Zambia had “absolutely no exchange controls”.

Hichilema also disclosed that the Africa Finance Corporation, leading the many countries financing of the Lobito Corridor, including the EU, US and Italy, had just confirmed that “bricks and mortar” construction of the corridor would probably start later this year. That would include not only connecting Angola to the DRC but also the Northwest line linking Zambia’s copperbelt to the corridor.

Hichilema said he was happy the Northwest line would be developed simultaneously with the other part of the corridor as there had been earlier talk of a two-phase construction.

Meanwhile he said Zambia had signed the $1.4-billion contract for the full rehabilitation of the 1970s Tazara Corridor, which goes east from Zambia’s copperbelt to Tanzania’s Dar es Salaam port.

Political reforms

Apart from economic reforms, Hichilema on coming to office in 2021, also launched political reforms, reversing the repression of his predecessor Edgar Lungu, including against Hichilema.

But has he gone far enough? Freedom House, which monitors the political rights and civil liberties in all countries, still rates Zambia as only “partly free”, explaining that “Zambia’s political system features regular multiparty elections, and some civil liberties are respected. However, opposition parties face onerous legal and practical obstacles to fair competition, and the government regularly invokes restrictive laws to narrow political space.”

Hichilema dismisses this criticism, insisting, “There’s no comparison of the democratic space prior to the 2021 elections, on 12th August, to what it is now.”

Lungu shut down some media, whereas Hichilema has shut none, he says. He thinks that perhaps the issue that such critics have is with the way the government handles social media abuse and cybersecurity.

“There’s no country that wants false news, accusations, hate speech to be promoted…that could lead to instability,” he says, defending his government’s restrictions on what he calls “hate news”.

He notes that while Lungu did not allow him to campaign for office, his opponents were out campaigning now.

“They are having meetings now to strategise how the opposition can come together to defeat us. And that’s their freedom. We have no issue.”

He says over the last few months there were two parliamentary by-elections, one in Chawama, which the opposition won and one in Kasama, which Hichilema’s United Party for National Development won.

“If… there was limited democratic space for them to come in, how did they win it?” he asked, adding that the bloodshed that used to accompany elections had now ended. DM

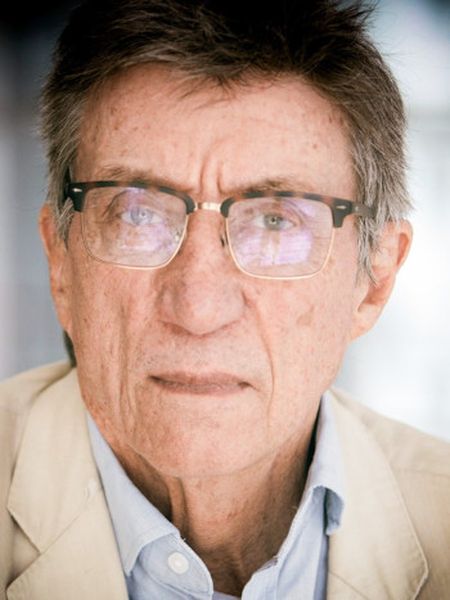

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema is confident he’ll win a second term in August 2026. (Photo: Tasos Katopodis / Getty Images for Prosper Africa)

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema is confident he’ll win a second term in August 2026. (Photo: Tasos Katopodis / Getty Images for Prosper Africa)