Electricity and water are two of South Africa’s most vital – and increasingly scarce – public resources. For good reason, their use is subject to strict regulation in terms of the National Water Act and the Electricity Regulation Act.

So any potential threats to the country’s water and energy security need to be considered seriously and subjected to wide public scrutiny and transparency.

And yet, several municipalities, Eskom and some government departments appear reluctant to play open cards in releasing information about the volumes of power and water demanded by current and planned data centres at the heart of the digital and Artificial Intelligence revolution.

/file/attachments/orphans/Tonydatapic19switchdatacentreinNevadaimageSwitch_FINAL_277659.jpg)

As we have shown in this investigation, data centres have become a significant consumer of both power and water at a global level (In parts of the United States, data centres suck away up to 25% of electricity at a state level. More than 20% of Ireland’s electricity and 7% of Singapore’s power are needed to fuel these energy-intensive data hubs).

Though current power and water demand from local data centres still appears to be low in comparison to bigger global players, no official statistics are readily available at a national or local level in South Africa – apart from the self-reported information provided by some (but not all) data centre companies in their annual sustainability reports.

Our Power Guzzlers series has also highlighted plans by at least two companies to significantly expand or build new data capacity in Johannesburg and Cape Town, cities that have both experienced the economic and social trauma of water stress and load shedding over recent years.

/file/attachments/orphans/Tonydatapic9teraco-jb4-data-centre-rooftop-imageTeraco_FINAL_617992.jpg)

Hoping to get a better understanding about power and water consumption at a more local level, Daily Maverick journalists began sending questions to Eskom and several municipalities in July 2025.

Six months later, however, most of our questions remained unanswered – ignored, evaded or blocked on the basis that such information is “confidential” in terms of the Protection of Personal Information Act (Popia) – even though water and most electricity supplies are public resources.

Eskom did not provide us with any data on current and predicted electricity use by data centres, simply noting that it was “closely monitoring both global and local developments in the data centre industry, including the anticipated increase in energy demand driven by advancements in Artificial Intelligence”.

“While specific volumes cannot be quantified at this stage, these trends are being carefully considered and integrated into Eskom’s long-term system planning to ensure that the national grid remains reliable, flexible and well positioned to support future economic growth.”

Power demand from data centres was being accommodated from existing generation and network capacity, and the utility was “engaging with industry stakeholders to ensure this growth is effectively planned for and integrated into the broader electricity system”.

In response to follow-up questions, Eskom said it was “unable to provide any customer-specific information”

“In terms of the Protection of Personal Information Act, Eskom is legally obligated to protect the personal information of its customers and may not disclose identifiable data to third parties, including the media. While we remain committed to transparency, we cannot release information that may compromise customer privacy or the integrity and security of the electricity supply system.”

/file/attachments/orphans/Tonydatapics23TheCitadeldatacentreinNevadaUSASourceSwitch_FINAL_708775.jpg)

At a municipal level, we received either no, or mostly incomplete answers.

The City of Johannesburg and the City of Ekurhuleni, while acknowledging our questions, have provided no responses whatsoever since 31 July and 18 November, respectively.

The City of Tshwane provided a 2025 spreadsheet of water meter readings for five (unnamed) commercial properties in the city, but refused to provide any data on electricity consumption on the basis that this was “private customer data”. Releasing this data without the explicit consent of the account holders would amount to a breach of their privacy, it believed.

“For each of the identified data centres, the city undertook the necessary network upgrades to support their connection needs. The most notable intervention was the upgrade of the Kosmosdal A Substation to accommodate the NTT Johannesburg 1 Data Centre in Centurion,” a spokesperson said.

“The city follows a comprehensive planning model that evaluates current capacity, analyses consumption trends, forecasts future growth, and increasingly incorporates the impact of alternative and embedded generation sources on the network.”

On water use, the city said: “Our review does not show unusual consumption patterns, although some accounts reflect high usage consistent with commercial activity.”

/file/attachments/orphans/Tonydatapic20VantageJoburgspecsfromVantagewebsite_FINAL_480251.jpg)

The City of Cape Town seems to be adopting a more cautious approach towards wooing more data centres.

Noting that the city’s energy directorate “may not comment on any customer information or business plans”, a spokesperson indicated that Cape Town was reviewing current investment incentive schemes for data centres.

“When the City’s Investment Facilitation Branch (IFB) and Energy teams meet with new prospective data centres, we encourage them to look for sites where there is sufficient electricity supply. This allows existing investments to be maximised, while ensuring the connection to the load can be done in the shortest possible time.

“Our Investment Incentives Policy is currently under review and going forward the revised policy does not provide any financial support specifically for data centres. However, our IFB remains ready to support businesses in bringing data centres to Cape Town while maintaining the highest sustainable standards.”

The Ethekwini municipality did not provide any information on the cumulative volumes of water or electricity used by data centres in Durban, even after Daily Maverick submitted a formal application in terms of the Promotion of Access to Information Act (Paia). That refusal is now under appeal.

The City said it was unable to provide answers because it did not keep records of data centres operating in the city and did not measure the collective consumption of these facilities.

However, the City acknowledged that “This is an area that requires further research, including understanding electricity demand and other potential impacts, to inform future policy development.”

Similar barriers to obtaining information on data centres have also emerged in the United States and elsewhere – including special incentive schemes and non-disclosure agreements between municipalities and data companies.

One example was the The Dalles city council in Oregon, which tried to sue a local newspaper to prevent the release of information on how much water was provided by the city to a large Google data centre. It argued that this was a “trade secret”.

However, The Dalles city council later agreed to release the data and abandon a 13-month legal fight to keep this information secret. The Oregonian newspaper said the affair raised questions about governments’ willingness to defer to large companies on matters of transparency and major public interest.

/file/attachments/orphans/Tonydatapic8AfricasubmarinecablenetworkSourcesubmarinecablemapcom_FINAL_444964.jpg)

Back in South Africa, the Department of Water and Sanitation said it could not provide any information on purified water use by data centres because municipalities were responsible for supplying potable water for domestic and industrial use.

However, data centres could also apply to the department for (raw) water use licenses.

“The Department has received two water use license applications, in the Western Cape and Johannesburg areas, for raw water for their cooling systems. Information from both applications indicate a combined demand of about 5,000 m3/annum.

“The water is sourced from groundwater resources (boreholes). Based on the information from the two applications, the conclusion we draw is that the demand for data centres is relatively small and it is authorised by way of a General Authorisation, which deals with low-risk economic activities. The applicants make use of highly efficient cooling systems, mindful of the fact that South Africa is a water-scarce country.”

“Based on the existing water demand, the Department is of the view that their increased water demand will be met without negatively impacting the existing groundwater resources.”

Electricity and Energy Minister Kgosientsho Ramokgopa was asked what specific plans were in place to ensure that further growth of data centres did not threaten power supply to the national grid. He said most data centres were embedded within the legal jurisdiction of licensed electricity distribution entities, which were responsible for such power supply.

“ Self-generation is also permissible in law and is subject to jurisdictional rules.”

Asked to provide data on cumulative power volumes supplied to data centres, a spokesperson said the national Electricity and Energy Department developed policies for the sector, but queries on “operational matters” should be directed to municipalities or Eskom.

On the risk of power price increases, the minister said affordability was an issue that affected all users and the government “has plans in place to ensure sufficient supply of electricity and to meet projected demand”. DM

* Additional reporting by Lindsey Scheepers, Julia Evans, Kristin Engel and Ethan van Diemen

This article was made possible in part through support from the Henry Nxumalo Foundation.

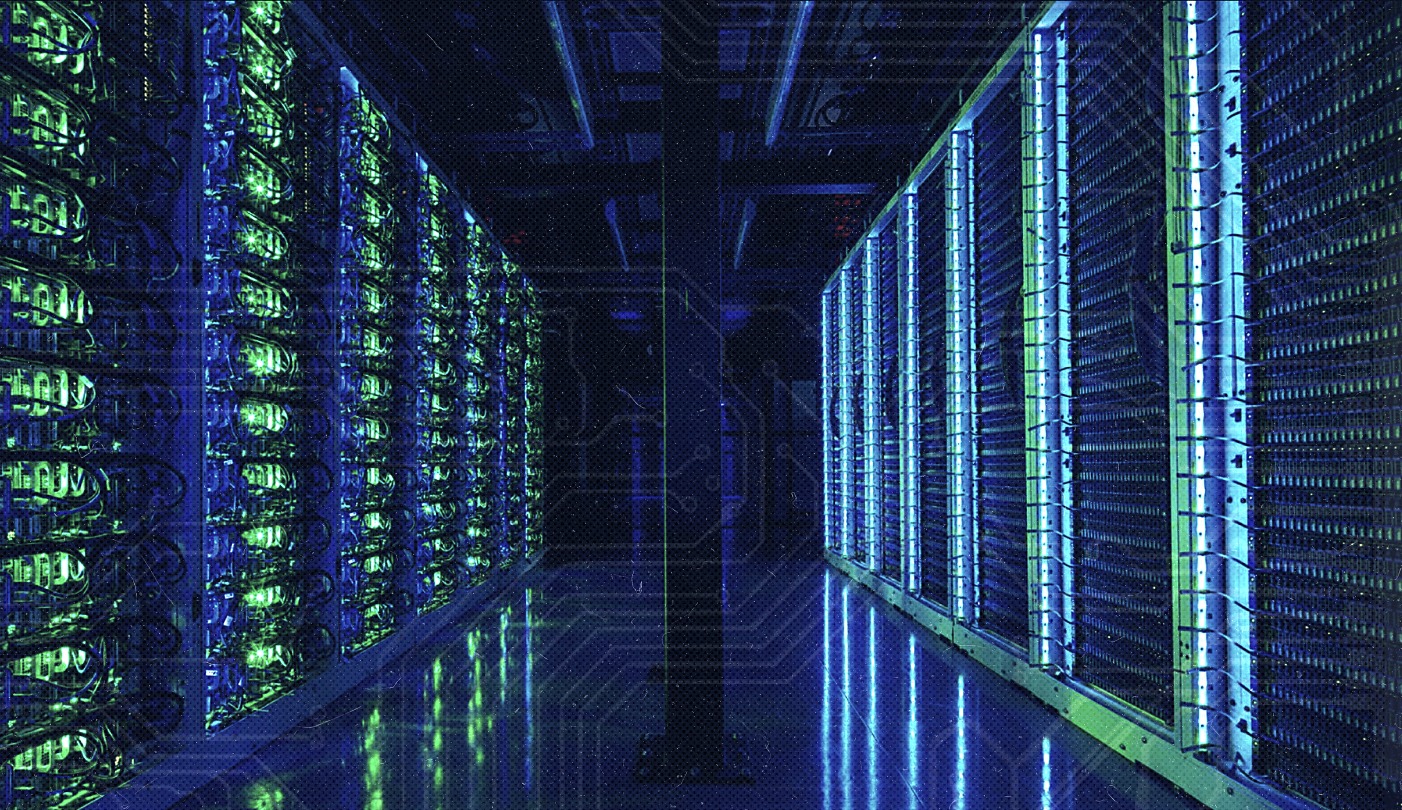

A typical interior view of a modern data centre. (Source: Switch)

A typical interior view of a modern data centre. (Source: Switch)