/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/label-Op-Ed.jpg)

This month, more South Africans than ever celebrated the news that their children passed matric, with the country’s highest pass rate in history (88%). But if you look a little closer, the details tell a much more complex story.

Our marks are not improving, which may seem discordant when we see more and more top African scientists shining on the global stage.

South Africa’s 2025 maths pass rate fell from 69% to 64%, and physics plateaued around 77%, only rising by 1%.

/file/attachments/orphans/Prof-Ncoza-Dlova-engages-learners-at-Njaloba-Secondary-School_680231.jpg)

Minister of Basic Education Siviwe Gwarube also noted that in 2025, only 42% of kids aged four to five were developmentally on track with early numeracy. The latest global TIMSS data also shows a significant drop in our primary school maths marks – worse than half of all countries surveyed.

This poor performance doesn’t just affect individual young people’s lives. It hampers innovation and has a significant impact on the economy. It indicates that we haven’t come far enough since apartheid’s discriminatory maths exclusion laws. And it impacts on SA’s ability to “meet the challenges of the future, like AI, climate change, energy and sustainable development”, in the words of Vijay Reddy, author of the South African Public Relationship with Science Survey, undertaken by the Human Sciences Research Council.

So, this International Day of Education, you’d be forgiven for wanting to jump right in to try to solve the blatant issues with South Africa’s education system – especially if you’re a scientist.

Scientists solve problems. That’s their thing.

But the solution is not only about improving resources and funding to schools (although this would certainly help). A far more pragmatic approach may be to inspire and foster the talent that already exists in our classrooms.

And that’s something that scientists and innovators can start doing, today.

/file/attachments/orphans/Archeologist-Dr-Ndukuyakhe-Ndlovu-engages-with-learners-at-Game-Pass-Shelter-in-the-KwaZulu-Natal-Drakensberg-_312797.jpg)

Excellence is everywhere

Some of South Africa’s maths and science learners are excelling globally and raising the profile of African knowledge, despite a widespread lack of basic schooling resources across the nation. A familiar tale amid the devastating inequality experienced in our country.

In December, four young scientists won top honours at the World Innovative Science Project Olympiad (WISPO) in Bali, earning prestigious Grand Awards for their innovative projects.

/file/attachments/orphans/Dr-Nadeem-Oozeer-at-the-site-of-the-SKA-radio-telescope-near-Carnarvon-Northern-Cape_463851.jpg)

In more established cohorts, UCT Professor Lynne Shannon was awarded the 2025 Prince Albert Grand Medal for Ocean Science, the first researcher in the entire Global South to win the distinguished accolade.

We are not lacking in talent. We just need to help foster it.

/file/attachments/orphans/Radio-astronomer-and-astrophysicist-Dr-Sphesihle-Makhathini-at-a-national-science-week-event-on-klight-based-tech_450768.jpg)

/file/attachments/orphans/Glenstantia_school_visit-4_145825.jpg)

If talent is not bolstered by exposure and belief at all levels of schooling, there is little chance of inherent aptitude being brought to its full potential, even with ideal resources in place … kind of like a loaf of bread being left to rise in a dank, dark environment where it simply cannot expand, no matter how perfect its ingredients.

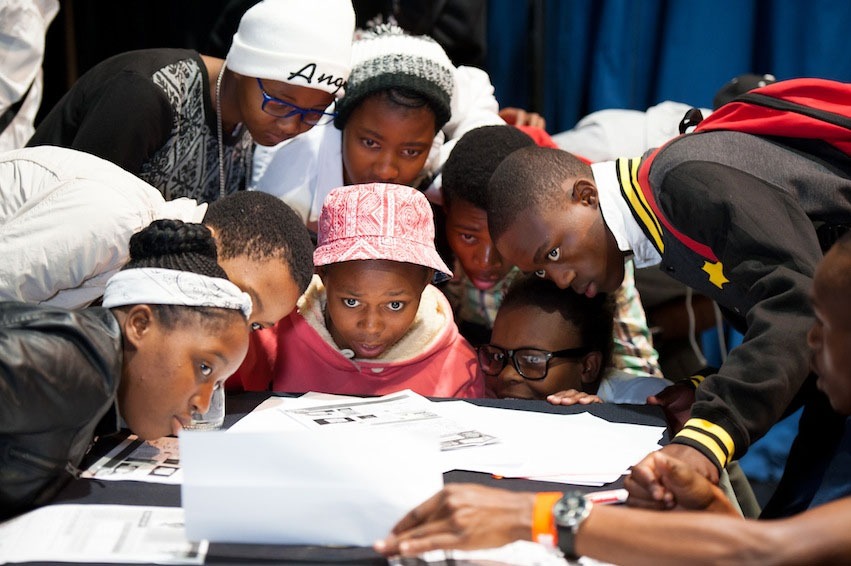

Scientists can play a huge role in inspiring and proving to students that it is for them, and that they’re capable of overcoming the challenges they will encounter along the way. This can happen simply by showing up and putting out exciting science where young people can engage with it, in their own language, and on their own terms.

Three ways for scientists to make a difference

My research is focused on the role of scientists in schools, not primarily as educators, but as role models. What I’ve found is that simply by facilitating conversations with young people about science as a tool for creating alternative futures, we can tangibly change education outcomes. Here are some ideas to help scientists do this:

1. Diverse visibility

Research by Marina Joubert from the Centre for Research on Evaluation, Science and Technology (Crest) in 2017 found that while “only 8% of South Africans are white, 78% of the group of ‘visible’ scientists were white, and 63% of the visible scientists were men. Only 17 black women were identified as publicly visible scientists.”

In any career, you cannot be what you cannot see. Early visibility of scientists of every race, gender and class is vital to help young people to see themselves in the field, and not just the image of a wealthy, white, lab-coated male. This will go a long way to developing the next generation of African investigators and problem solvers.

2. Presence

Unfortunately, seeing scientists at all is often more of a hurdle. So, scientists should take every opportunity to place themselves in the media, especially into spaces in which young people can engage.For many young people in under-resourced schools or regions, exposure to any working scientists or their stories is rare.

Many children have little or no knowledge of how their unique talents and passions could lead them into highly fulfilling careers and the opportunity to contribute meaningfully and valuably to the sector, and to society at large. Each of us can think back to a childhood encounter that inspired us or motivated us in a particular direction.

The presence of scientists and their stories in the lives of young people is a practical, proven, high-level way that we can contribute to South Africa’s long-term improvement in education.

3. Storytelling

Science is, contrary to popular belief, not all about numbers and chemical symbols. It’s about stories: of how people have solved the world’s biggest problems or changed their own lives through innovation, and ancient or alternative ways of thinking. When you frame concepts like this – real people doing amazing things – it’s suddenly much more compelling or easy to engage with new ideas as a young person.

Our national Science Spaza programme has been a great example for me of the efficacy of this “visibility, presence, storytelling” thinking in action.

/file/attachments/orphans/Dermatologist-Prof-Ncoza-Dlova-answers-learners-questions-about-skincare-at-Njaloba-Secondary-School-in-Howick-KwaZulu-Natal_707047.jpg)

Through Science Spaza, we distribute real stories of African scientists and innovators in engaging formats (such as comics, videos or interactive worksheets) to curious young minds aged 12-18. We’ve seen time and time again how this human, story-based, fun approach makes science more relevant, relatable and exciting.

Over the past 11 years, learners across our 120+ science clubs have seen their marks improve, career pathways open up and general passion for increase – simply by seeing scientists like them reflected back to them, and learning about the powerful ways that science and maths are being used in the world to transform lives for the better.

/file/attachments/orphans/Goratileoni-Oepeng-a-former-science-club-organiser-and-now-an-entemologist-_578242.jpg)

One high school student, Goratileone Oepeng, began a science club and registered it with Science Spaza to receive newspapers and activity worksheets. Years later, he won the FameLab heat at the University of Pretoria, where he was a master’s student in entomology. I recently bumped into him at the Oppenheimer Research Conference, where he was giving a young researcher spotlight talk, a champion for bees and biodiversity.

Make a difference

By getting scientists and their stories into schools, we’re not just filling a resource gap; we’re also showing kids that science is theirs for the taking. It’s about identity, not just ideas.

/file/attachments/orphans/Dr-Nonny-Vilakazi-a-paleo-scientist-engaging-with-learners-on-SAs-rich-paleo-history_598157.jpg)

If you’re a scientist, you have the power to make a difference – it’s just not where you might expect it.

Sure, we need funding and teachers and classrooms. But my research has shown that so often, we make the mistake of thinking we can jump in and solve systemic issues all at once, without focusing on tangible ways to foster the talent that already exists in schools, and ensure it reaches the global stage. We need scientists to inspire young people to follow in their footsteps, which will, in turn, encourage them to dedicate themselves to learning.

No matter what field your research is in, there are probably more ways you could be sharing your work with local schools or supporting the next generation to become involved – by showing up in person, embracing the media to tell your stories of science, or by contributing to resources that students can engage with to learn not just about your research, but about YOU.

Maybe you look like them.

Maybe you’ve had an inspiring journey to get to where you are.

Or maybe you’re simply the first scientist they’ve ever seen.

Whatever your story, it’s worth sharing.

Not just for you, or for students and their learning outcomes, but for South Africa’s future and African knowledge as a whole. DM

Robert Inglis is co-founder of the Science Spaza youth science engagement initiative and director of Jive Media Africa, a science engagement and communication agency which has provided support to the research sector for more than 20 years.

Learners engage with radio astronomer and astrophysicist Dr Sphesihle Makhathini on light-based technologies. (Photo: Supplied)

Learners engage with radio astronomer and astrophysicist Dr Sphesihle Makhathini on light-based technologies. (Photo: Supplied)