/file/attachments/2985/Troubledwatersfinal_368491.jpg)

Kalk Bay harbour on the False Bay coast was once alive with boats, crew and families making their living from the sea. For generations, the Poggenpoel family has been part of that story. Today, 72-year-old Kobus Poggenpoel sits beside his boat Melissa Kelly, looking out over a harbour that feels more like a museum than a working port.

I spoke to him about the boats themselves – their history, how they were built, how they worked — and about why, these days, they mostly lie tied to the quay.

How old is your boat?

That boat, Melissa Kelly, we had her since 1978. Built in Vredenberg, by Sagel, good boat-builders, very good people. A lot of boats came out of there. Before that, we had other boats — Mary and Dawn, Ana Amelia. Our family always tried to build up boats.

My dad and his brothers, they worked [on] other people’s boats first — Mr Williams, Mr Klein. Then my uncle said, no, let’s work for ourselves. So they bought Tessabee, worked her off, renamed her Ana Amelia after my grandmother. From there the family grew into boats. At one stage we had four. Now we only got two left — Melissa Kelly and Mary and Dawn.

Who built Mary and Dawn?

She’s an all-wood boat. Built by Lowen Harveston in the docks. Solid hardwood. Those days they imported the wood, you got it in Woodstock. Everything by hand — planks, seams, caulking. The old way.

And Melissa Kelly, what’s she made of?

She’s mixed. Bottom hull: glass fibre; cabin: glass fibre; but the gunwales and bulwarks: still wood. That’s how they built in the seventies — half and half.

Why the name Melissa Kelly?

[Laughs] Names, always an argument in the Kelly after two granddaughters in the family, Melissa and Kelly. That way, no arguments. Names change, but the boat stays in the family.

/file/attachments/2985/KobusPoggenpoelDonPinnock_565447_5321a19a8ff58018e435c75bdb0e2be9.jpg)

Your grandfather also had boats?

Yes, three little double-ender whaling boats with sails. Navy type. Not for whales — just the style. Everything [was] hand-line in those years. They’d row out, fish with hand-lines, bring back snoek, mackerel, stumpnose. That’s how our family started here.

How did you fish with the bigger boats later?

Purse-seining mostly and also to pole tuna. You’ve got your net, you drop bakkielig — a marker buoy — then a sea anchor. You circle the fish, close the net, pull tight. Before we had pumps we used to scoop by hand, bail the fish out into the hold, cover with ice slurry — ice and water mixed — to keep them fresh. Before slurry we used salt. Throw salt over the fish in the hold. But slurry made better quality.

How do you know where the fish are?

You learn to read the sea. First, you look for the seals. If the seals are jumping, there’s fish underneath. Then the birds. They’ll take you straight to the shoals. You can also see it — a red layer on top of the water. Nowadays they use sonar, fancy machines. But in my time, eyes and seals and birds, that was enough.

How many crew did you take on Melissa?

Twelve men when we seined. Everyone had a place: wheelman, sternman, net pullers. On Mary and Dawn we could take 14. For line-fishing, fewer, maybe seven. It was heavy work. But when the snoek were running, you could fill the boat.

/file/attachments/2985/DirkPoggenpoelKobusPoggenpoel_919890_5fe179d5ccecef01a3d0a0886685c9a2.jpg)

What about the maintenance?

Boats cost money even if they don’t go to sea. Engines — oil, filters, belts. Wood needs repainting, caulking. Survey every year — flares, jackets, life rafts. We did most of it ourselves. Only the big engine jobs went to the engineering people. You’ve always got to keep a boat ready, because if a chance comes, you must go.

Any scary times out there?

Oh ja. Once we came from Danger Point, boat full of fish. Northwest wind blew so hard the boat just stood still. Shuddering, not moving. The current carried us, and then we’d try again. Push past Seal Island, then turn and surf the waves home. But we knew the sea. If the wind starts to pick up, you say no, anchor up, go home. Don’t take chances.

What was Kalk Bay like in your younger days?

Alive. Boats going out, coming back heavy with fish. Horse carts waiting. People from the Flats coming to buy. Families working together. Our boats always gave 60% of the catch to the crew, 40% to the owners. We never exploited anyone. That way, everyone made a living. The harbour fed people all over.

And today?

Today? Dead. Boats just lying here. Tourists take photos, film crews hire the boat sometimes. But no fishing. Last year, Melissa went out once — one trip. Mary and Dawn hasn’t worked in two, three years. Quotas too small, licences delayed, permits late. By the time you get the paper, the season’s gone.

Why are the quotas such a problem?

The department listens to scientists, not fishermen. We’ve got logbooks — every trip, where we went, what we caught. That’s real data. But they don’t look at it. They cut us down — 37,000 tonnes for the whole small-boat sector. How must hundreds of boats survive on that?

Meanwhile, the big trawlers drag nets offshore, catch everything. By the time the bag comes up, everything’s dead. We, the small boats, we fish with respect. We choose species, we throw back undersized alive. They don’t. Yet we get punished.

/file/attachments/2985/KobusPogenpoelandKalkBayHarbourwheremanyboatsbobunusedDonPinnock_769312_67e476e94a2083a08d47ce9ca5b1d38e.jpg)

You spoke about snoek running down the coast. Does that still happen?

Not like before. Used to start in Walvis Bay, Port Nolloth, Lambert’s Bay, Cape Point, Hermanus. We followed them. But too much pressure further north, lights at night, sonars. Snoek doesn’t reach us the same any more.

What about your crews now?

Most of them gone. Some find work on ski boats. Some just left fishing. Once a crew breaks up, it’s hard to bring them back. Youngsters don’t want this life any more — they see no future.

If things were different, what would bring the harbour alive again?

Licences. That’s the key. Give the small boats rights to fish properly, not just one species. Let us work like we did in the 60s, 70s, 80s. Kalk Bay could live again. But now … nothing.

***

At the end of the interview, Poggenpoel looks across the boats lying idle. His voice drops. “As a fishing harbour, Kalk Bay is dead, and I don’t know how it can be revived. Our children look at our troubles and don’t see a fishing future. I’m 72 and these traditions will die with my generation. It’s sad.” DM

Tomorrow

Travis Daniels: at one with the sea

Previously

Setting up the series: Untangling South Africa’s fishing industry

Mark Wiley: South Africa’s vanishing fish

Tim Reddell: Steering Viking Fishing through South Africa’s troubled waters

Deon van Zyl: “We’re crippled by government inefficiency”

Doug Butterworth: seafood’s balancing act and the science of sustainable catch limits

Colin Attwood: Counting the uncountable and the science of tracking fish

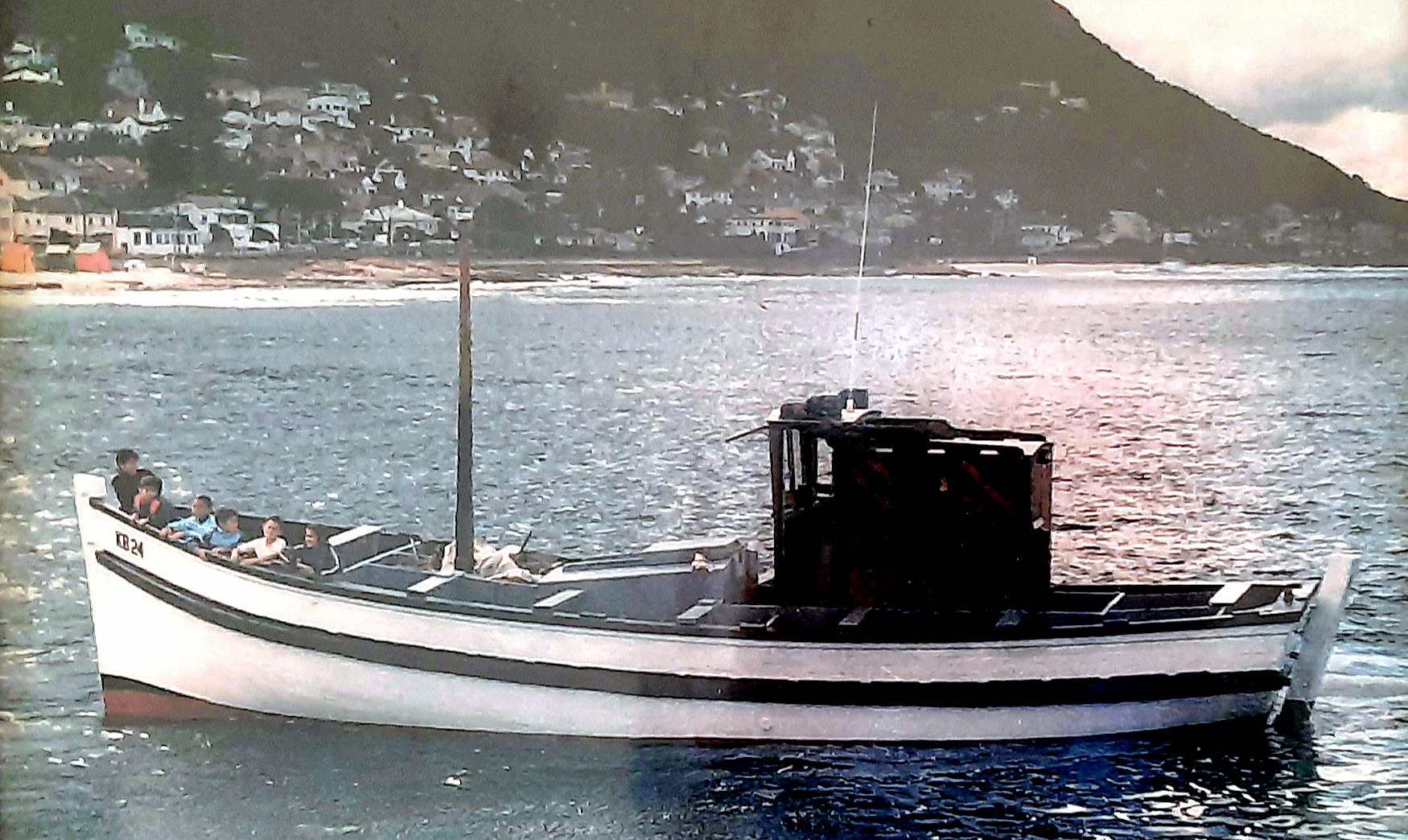

A hand-line fishing boat in Kalk Bay in the 1940s. (Photo: Tony Trimmel)

A hand-line fishing boat in Kalk Bay in the 1940s. (Photo: Tony Trimmel)