/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/label-analysis-2.jpg)

How President Cyril Ramaphosa eventually appointed Andy Mothibi as the new National Director of Public Prosecutions, and the recent revelations about corruption at the top of the SAPS, show that reform of the leadership selection process is needed. The door might be opening for Ramaphosa to change the way these appointments are made, and so to force more transparency into the system.

Last week, in a surprise announcement, Ramaphosa revealed he had appointed Mothibi as the new head of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA), to take over at the end of January.

The main reason for the surprise was that Mothibi was not among those interviewed in public by the panel set up expressly for this purpose.

Ramaphosa says the panel found that none of the candidates was suitable. Given that several candidates, including Hermione Cronje, had years of prosecutorial experience and had held senior positions in the past, this is incredibly surprising.

The real problem was probably with the panel in the first place. It simply did not have the right people to make a recommendation. It had no prosecutors and there was no justification for including some lawyer bodies while excluding others.

Its decision to include Menzi Simelane on its shortlist was clearly illegal and made the entire process vulnerable to legal challenge.

In the end, it seems Ramaphosa simply bypassed the panel and used the provision in the law that allows the President to make the appointment (so long as the person is suitable and qualified).

While Mothibi has a stellar track record, as Rebecca Davis has noted, the entire affair should and could have been conducted differently.

While Mothibi is an impressive candidate to run the NPA, in essence, Ramaphosa took us back to the State Capture era when then president Jacob Zuma simply appointed whom he wanted to run the NPA.

With results that were plain to see.

Precedent

This precedent set by Ramaphosa can now be followed by whoever succeeds him. There would be no way to force a Paul Mashatile or a John Steenhuisen or a Julius Malema to follow a transparent process were they ever to become President.

At the same time, the revelations late last year in the Madlanga Commission reveal a police leadership that appears to be riven with corruption and factionalism.

While National Police Commissioner Fannie Masemola has not been tied to corrupt acts at this stage, and was not named by KwaZulu-Natal provincial commissioner Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, he has shown himself sensitive to political implications.

His comment that it would be “career-limiting” to argue with or disobey now-sidelined police minister Senzo Mchunu’s “instruction” to shut down the Political Killings Task Team shows how political control works in the SAPS (even though the police minister does not have any operational control over the SAPS; this is purely the domain of the national commissioner).

The root of this power is the fact that this appointment is in the hands of just one person, the President.

Ramaphosa himself has said repeatedly that one of his major tasks has been to strengthen and reform our institutions.

Certainly, he has tried very hard to do this. SARS, the NPA and many other institutions are very different to what they were 10 years ago.

The main task now may be to lock this in for the future.

The key to this is to reform the way leadership appointments are made – and because it is not clear who will take over from Ramaphosa, it is probably necessary to change the law.

Smoother political path

Thankfully for Ramaphosa, this might be politically easy.

First, the process of appointing Mothibi has reminded people how much power a President has, and why this is unwise.

Second, it is likely that a political head of steam will build up to find ways to reform the SAPS. So many have been so shocked at the testimony heard by the various inquiries, and so self-interested have been some of the officials, that it would be hard to argue against change.

Given the fact violent crime is such a major feature of the lives of so many of our people, there will be demands for change.

But a key element is required for any of these changes to happen.

They must be signed into law by a President who is, in effect, giving up some of their power.

This will only happen when a President is both about to finish their term and not handing over to a close ally.

Ramaphosa might well find himself in that position in about two years.

It also requires other parties to agree to the change. Considering that no party is assured of supplying a President in the future, it is likely that people as different as those from the DA and MK might agree to this change.

However, there may also need to be a discussion about people serving in below-the-top jobs in the NPA and the SAPS.

Appointment powers

Currently, the President has the power to appoint (in consultation with the NDPP and the justice minister) “up to four Deputy National Directors of Public Prosecutions”. The person in that post also formally appoints the Provincial Directors of Public Prosecutions in consultation with the NDPP.

This means that only the President can suspend those people.

As has been seen in the recent past, this places a huge amount of power in the hands of one person.

Despite what appeared to be overwhelming evidence against South Gauteng prosecutions boss Andrew Chauke, Ramaphosa took nearly two years to act on a request from the current NPA head, Shamila Batohi, to suspend him.

While there is no claim of a political motive for this, a very similar situation could arise in the future in which there is a distinct political motive.

In the SAPS, provincial commissioners are appointed by the national commissioner in consultation with the premier of that province.

This also means that a President has ultimate control, because they appointed the national commissioner.

Of course, the nature of these changes will be highly contested.

Having a panel and a public process does not, on its own, necessarily improve the outcome.

As the Judicial Service Commission has shown in the past, political agendas and large personalities can take over these proceedings. This can also prevent some candidates from making themselves available.

On balance, public interviews would seem necessary in these processes, to give their outcomes legitimacy. But the political arguments over who would conduct the interviews could be intense.

This may well become the focal point of any debate about such a change.

Of course, this will not happen on its own. It would require pressure from civil society.

But the window for change may soon start to close. Which means anyone who wants this change to happen should start applying pressure now. DM

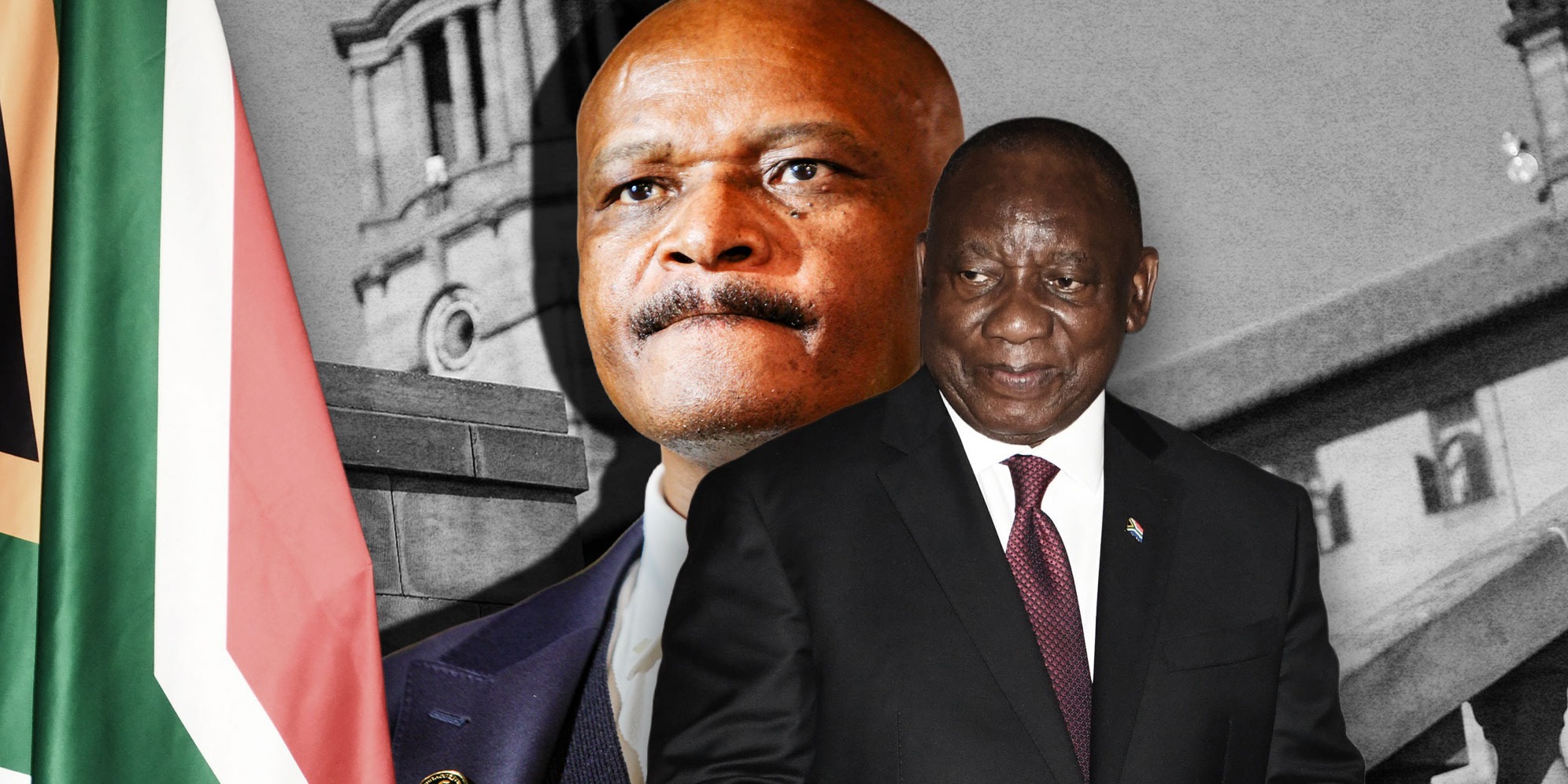

Illustrative Image: Union Buildings. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Alaister Russell) | Andy Mothibi (left). (Photo: Gallo Images / OJ KolotI) | President Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Frennie Shivambu) | (By Daniella Lee Ming Yesca)

Illustrative Image: Union Buildings. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sunday Times / Alaister Russell) | Andy Mothibi (left). (Photo: Gallo Images / OJ KolotI) | President Cyril Ramaphosa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Frennie Shivambu) | (By Daniella Lee Ming Yesca)