Twas the afternoon before Christmas and through in the kitchen, a creature was stirring: a pot of barszcz czerwony. Nestled snug in her bed (to continue borrowing from the classic Christmas poem) in an adjoining room is Danuta Miloszewski, 96 years old. One of not-too-many still-living “Polish children of Oudtshoorn”, Danuta represents an extraordinary WW2 story that few visitors to Oudtshoorn, few South Africans, few Poles, know about.

It is her daughter, Jola Miloszewski, who is making what is a simplified version of the classic Polish Christmas eve beetroot soup, which at its most traditional would have a base of fermented beet juice. But hers?

When I ask about the recipe, she tells me she “boils the bejesus out of two bunches of beetroot, two bunches of carrots, onion, celery, bay leaves, peppercorns, water, salt and pepper to taste — we gooi in some garlic, which I am sure is not traditional; grate the beetroot when it’s cooked and push it through a sieve. I keep the pulp to serve later as a veggie, either sweet-and-sour or with cream. Strain the boiled juice of the other ingredients and mix this with the beetroot. And that’s it…”

Jola trained as a chef, years back, in Johannesburg. Has worked in restaurants. Done private catering. Ran Durban’s Highway Hospice kitchen for five years. From her recipe description, you’ve maybe gathered that she is funny, friendly, no-nonsense and not one to beat about the bush.

She didn’t expect her mom, Danuta, to make it to Christmas 2025. There’s a matter-of-fact lack of sentimentality when she tells me this. The kind that comes when you see a parent’s quality of life reduced, have an acceptance of the inevitable, know there has been a life well-lived and that you’ve done your best.

And the thing is, last year, this year, next year, regardless of circumstances, the Polish Christmas tradition of wigilia — something Jola has celebrated all her life — will live on.

She will make the barszcz (soup) and the little “floaters” as she calls them, or uszka, tiny dumplings filled with fried reconstituted dried mushrooms, fresh portabellini mushrooms, onions and herbs, which will go into the soup.

Also, her simplified version of pierogi, the Polish dumplings she stuffs with boiled and mashed potatoes, cottage cheese and fried onions… “You can make them in advance and freeze them. On the day you will eat them, you fry them with butter and serve them with cream. Your heart implodes — that’s Polish food for you — and you carry on eating.”

/file/attachments/2986/Danuta_one_810529_2f5537d722e8fd9ecda5d523cbb224bb.jpeg)

If you tell me you’re going to Oudtshoorn, I will assume you want to visit the Cango Caves. Or the ostrich farms, given that Oudtshoorn tags itself the “ostrich capital of the world”.

But neither caves nor ostriches are why Danuta Anna Magielska — as she was born 96 years ago on 23 July, 1929 near Warsaw — found herself in Oudtshoorn.

She was 13 years old when she arrived in Port Elizabeth on 10 April, 1943 from Siberia via Persia, aboard the British vessel, HMT Dunera; one of 500 Polish refugee children of Oudtshoorn, “who survived the WW2 deportations to Siberia and later escaped the USSR to find refuge in Africa,” to quote from the Facebook page of the Warsaw-based Polish government Institute of National Remembrance (INR), which co-funded a commemorative monument unveiled in Oudtshoorn on Heritage Day, 24 September, 2025.

Danuta and her mother were among hundreds of thousands of Poles snatched from their homes and deported, on Stalin’s orders, to gulags in Siberia. To quote historian and author Norman Davies, for context: “From 1939 to 1941 … up to two million Polish citizens were deported by Stalin into the depths of Central Asia and Siberia. At that time, Poland was divided by its two conquerers, the Nazi Germans in the West and the Soviets in the East. These people were removed for no other reason than they were Polish and belonged to certain social categories.

“The Nazis destroyed people according to pseudo racial principles. Stalin destroyed people according to political and social categories and the people he deported from Poland in 1940 and 1941 were state employees, teachers, railway officials, bureaucrats, politicians of all sorts, and any category that disliked him, like stamp collectors and esperantists. And these deportees, half of whom died within a year or so in Siberia, formed a pool of people many thousands of miles from home…”

/file/attachments/2986/Collage_Monument_250986_327235bcb056d26f4d1985f6c7540d54.jpeg)

To quote historian and author Adam Zamoyski from his book, Poland: A History: “It is a grim irony that although it had been a member of the victorious alliance, Poland was the ultimate loser of the Second World War. It lost its independence and almost half its territory — in defence of which the war had been declared…

“Nearly six million Polish citizens had been killed, a proportion of one in five. The proportion among the educated elites was far higher: nearly one in three for Catholic priests and doctors and over one in two for lawyers. A further half a million Polish citizens had been crippled for life and a million children had been orphaned. Another half a million Polish citizens, including a high portion of the intelligentsia, most of the political and military leadership, and many of the best writers and artists, had been scattered around the world, never to return. In all, post-war Poland had 30 percent fewer inhabitants than the Poland of 1939…

“Both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia were determined to destroy Polish society. They therefore imported onto the multi-ethnic and socially diverse territory of Poland methods of racial, social and political manipulation they had developed in their own countries. It was these that tipped the realities of the war in occupied Poland into a circle of hell far below that reached in any other country…”

Fast-forward to Oudtshoorn, 24 September 2025. A large gathering, on a sunny day, attend the dedication of the monument memorialising the 500 children and their caregivers. The driving force behind the memorial is Stefan Szewczuk, president of the Polish Association of Siberian Deportees of South Africa, in cooperation with the Embassy of the Republic of Poland in Pretoria, the CP Nel Museum — where the monument is located — and representatives of the previously mentioned Warsaw-based INR.

/file/attachments/2986/Danuta_two_452165_ce93076cb7bc92478e4a510d8ea88a3d.jpeg)

A curious synchronicity takes me into the home, into the life of Danuta Miloszewski, this 96-year-old pra babcia (great grandma), as she is affectionately called by her family, including five great-grandchildren. Danuta lives with her second-born daughter, Jola Miloszewski, and son-in-law, Dean Tennant. (JD Electrical, Jola and Dean, is their company.)

I meet Danuta for the first time about two weeks after Dean comes to check on some problem electrics at our little apartment block. He is one of those rare “essential people” it is a delight, never a mission, to have to call in.

I’d long known that Dean’s wife, Jola, was Polish and loved dogs. I also knew that Jola’s mom, old and increasingly frail, lived with them. I would typically ask Dean, more tentatively each year, “How’s Jola’s mom?”

This time, conversation turns to the “roots” memoir I’m writing, focused on my late Polish dad. I tell Dean about the pile of “Alfons” documents I had taken to the Museum of Emigration in Gdynia. Documents being digitised for their collection via a Polish government grant. I tell Dean I will include something about Poles in South Africa, seeing my dad settled here after WW2. For instance, the Polish children of Oudtshoorn.

“You do know Jola’s mom is one of the Oudtshoorn children?” he interjects.

“No! Really? Are you serious? I had no idea…”

“You could come and speak to her,” he says.

“Really? You think she wouldn’t mind? And Jola?”

“Just message Jola and make a time.” Wow.

The nightmare that defined her life

On that first visit back in April 2025, I am surprised that someone so visibly frail and barely mobile, even with her walker, can have such an effervescence, a vibrancy, a zest, even when she bemoans the physical failings of her advanced age. Points to the tissue-paper skin on her arm. “The dog jumped on me. Hardly touched me and that happened.”

Slim as a twig, she is stylishly dressed in what I think of as Polish red. A hint of lipstick to match. A perky tint enlivens her hair. She is dressed for church, Jola explains. Ready to leave at 4pm, to be driven to the Palm Sunday Mass at the nearby Catholic church.

Watching her and keeping an eye on me, between dozing, is the family’s ancient, partially sighted dog. “That’s Evie Wonder, Stevie Wonder’s niece,” Jola says, by way of introduction to the tail-wagging grizzled pooch. It takes me a few seconds to get it. Not that long to get, though, is an appreciation of the warmth, the affection, bubbling through the house.

Jola is Danuta’s youngest daughter, born 17 years after the second of her two siblings, a sister who died in 2023. Jola is the only one who learned and then maintained her Polish, and she and her mom seamlessly knit English and Polish. “It was my first language.”

She in fact couldn’t speak English when she started school. “I had the funny surname and everyone thought my parents were my grandparents.”

/file/attachments/2986/ExtraPicpic5spot_328765_39238deaf4ebcdc4611f324dfbb644ed.jpeg)

Back to 1941, Poland. Danuta was 11 years old when the pounding on the door, shortly after midnight, ripped the silence of what had been a tranquil night at her grandfather’s mountainside village house in the Krzemieniec region in Eastern Poland. “Russian soldiers woke us up and took my mom and me.” Whether her grandfather was killed then, or later, she’d never know.

After their abduction by Stalin’s soldiers, “we were put in cattle carts” along with hundreds of other Poles, similarly grabbed from homes and villages. “We were crammed in there for days with no idea where we were being taken.”

Every so often, the train would stop. The soldiers would slide open the side of the wagon. Usually, there was a glimpse of countryside. Some basic food was thrown in. Human excrement thrown out. Then the door was slammed shut again and the journey continued. Until, at some point, she is not clear on the time frame, the train stopped and they were bundled out.

“I can’t remember all the details. I’m nearly 96, I don’t know what I’m still doing here, a nuisance to everybody…”

Nobody in the family seems to think this. While I’m there, her granddaughter, the child of her second daughter, deceased, visiting South Africa from the UK and leaving for the airport later in the afternoon with her three children, comes to say goodbye. Danuta lights up. They all do. All three kids hug her goodbye. Hug me, too, which is happy-making.

Siberian labour camp potatoes

It was at the behest of Danuta’s dad, Josef Magielski, who worked at a bank, that Danuta’s mother, Genowefa Magielska, a teacher, had taken their ailing only child “away from the terrible bombardments happening all around” to stay at her grandfather’s in a rural village. Danuta would never see her father again or know how or by whom he was killed.

He, in turn, had no idea of the nightmare in store for his beloved wife and daughter. No notion that they would be snatched in the dead of night by gun-wielding Russian soldiers. Or that, after experiencing the horrors of a Siberian labour camp, his daughter would helplessly watch her mother die after a perilous sea journey to what was then Persia.

Danuta and her mom found themselves at a labour camp, one of many in Russian Siberia. Primitive, inhumane conditions. Called a labour camp for good reason, everyone had to work.

Her mother was put to work cooking. Danuta remembers the big pots. The children, herself included, had to dig potatoes in the hard-earth fields.

“I would steal a potato or two, hide them under my clothes when I could, for my mother to eat.”

She knew her mother wasn’t doing well…was being worn down by the demands and deplorable conditions in a camp. When her mother wasn’t cooking, she was sent to cut trees. “I’d wait for her as when they finished, it was getting dark and she couldn’t see.”

The story is long and dark. There are many links on the internet. Look up Anders Army for reference.

Danuta was among 41,000 troops and 74,000 civilians evacuated from Soviet soil in 1942. She found herself in Isfahan in Iran, orphaned when her mother died there, then put on the ship, the British vessel, HMT Dunera. Port Elizabeth, then Oudtshoorn. Always a Polish Catholic priest, a Polish teacher and attention paid to the children’s Polish heritage.

The stories she tells could fill a riveting, painful, lonely, happy-sad, fascinating memoir. Like, “I remember I was sleeping once and then I saw blood.” It was her first period. “I didn’t know what it was. There was a Red Cross person. She said, Don’t worry, darling.” And her young life carried on.

Danuta was sent to boarding school in George to finish her education. Then on to Durban, to a boarding house for girls, where she was given a ticket and expected to find a ship to take her back to Poland. But she had nobody there to go to.

/file/attachments/2986/Polska_tree_230795_8f029dc7871ef255a8b19652f4eca479.jpeg)

So she stayed and got a job, with her “very little English”, at the bank. Then, some Polish boys who had gone to work in Pietermaritzburg, who knew there were these Polish girls in Durban, asked them for Christmas lunch. There was “a lot of eye-fluttering” from one of the young men, Jola laughs, knowing the story.

“He put a plastic ring in my Christmas pudding,” Danuta smiles, eyes twinkling all these years later. “Then he started riding to Durban on his bicycle to visit me — and back again, as he couldn’t afford to stay over.”

It was Stanislow Miloszewski, also one of the “Polish children of Oudtshoorn”. The boys and girls had been kept apart, and the pair had never met.

They married, in Maritzburg, on 16 June 1951. “People in Pietermaritzburg heard there was this Polish couple getting married. Somebody donated cake. Somebody made me a wedding dress. Somebody arranged for the wedding party at the City Hall. All strangers. We were starting out. We had no money back then. It was unimaginable.”

Usually, for a Polish woman, the “ski” at the end of a name becomes “ska” when she marries and takes her husband’s name. “But the name in itself is challenging here in South Africa. To make things more simple and straightforward, I used the masculine ‘ski’ when we married.”

Jola’s dad, who became a successful businessman in Durban in the engineering field, died in 2008.

“My dad was my North Star,” she says. “He was the one who invited Polish seamen, anyone Polish he heard was in Durban, to our home. He was generous and gregarious. He was also stoic and strict. And he wrote beautiful poetry.”

Her dad was the main cook in the family, Jola says. “Danuta would help.”

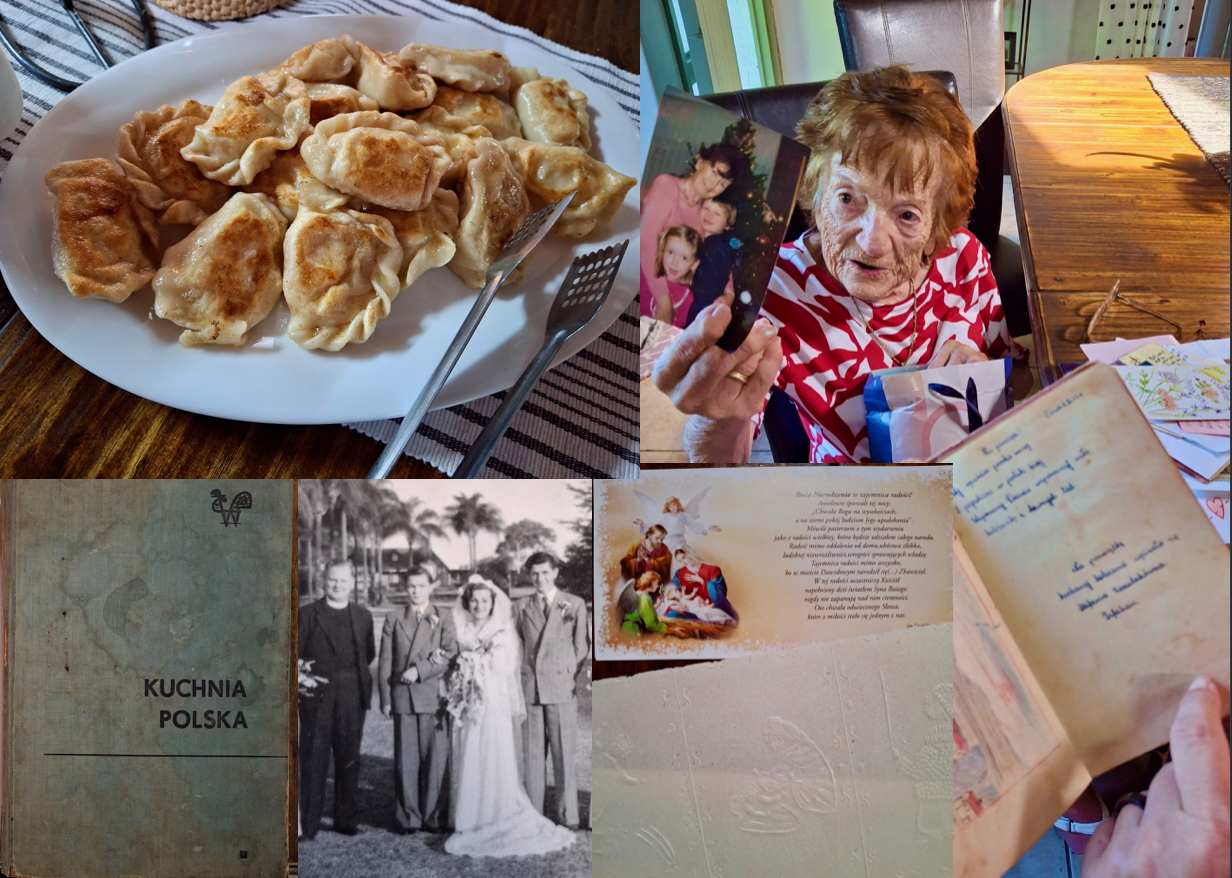

Jola brings out a well-used cookbook with a cover that says: Kuchnia Polska, which translates as Polish cuisine. “Every family among the Oudtshoorn children would have this book,” she says. “Where did they get it? I don’t know. People share, tell each other, keep tradition alive. This book is part of that.”

Polish Christmas, or wigilia, which translates as Christmas eve, happens — yes — on Christmas eve and has a number of traditions and requirements. There must be a Christmas tree, says Jola. There should be 12 courses. But she has let the 12 courses fall away. Herring, for instance: her dad, when she was growing up, would buy herring in a barrel. Change the iced water every day, clean and descale them. “You don’t get them now.”

/file/attachments/2986/Uszka_247183_492c63722e4b1a84f81fb2d8c1feb72a.jpeg)

The “floaters” or uszka and the beetroot soup, the barszcz. “That and the pierogi, I’ll have at Christmas until my dying day,” says Jola.

At the table, traditions include sharing the opłatek or Christmas wafer, like a large break-apart Catholic holy communion host. You share it with others at the table to reconcile, make peace, create a bond. “It’s not religious, it’s tradition,” says Jola. A tradition that, now that the table is smaller, they no longer include. But putting straw under the tablecloth, which represents the birth in the manger, she does.

Also, the tradition of having one extra seat at the table. For a stranger who might arrive. Or to represent someone special who is not there. I am lucky this year. By Christmas 2025, Danuta was too weak to sit at the table. She still wanted her barszcz and her pierogi to nibble on with her bird-like appetite.

With Danuta not physically strong enough to be at the table, I am invited to fill the seat.

Why I say not physically strong enough, come Christmas, she was still mentally ballsy and seemed to hear and see: probably better than I can.

/file/attachments/2986/Pierogi_724211_149f229a0d627e904eb1ca5ea88a025f.jpeg)

The dough for the uszka is the same as the pierogi dough. Just that these are smaller, folded differently, and have the mushroom filling. They are also prepared ahead of time. Then dropped into the beetroot consommé, with its delicate yet robust and rather beautiful, distinctive flavour. I suspect Jola’s French-focused chef training plays into all she prepares.

The dough is simply a combination of flour, salt, a little melted butter and water to bind.

“When my dad was alive, we’d start on the pierogi about 10 days ahead, the rolling, the cutting, the preparation. We would be making, often, for 30 people and you would roll until your arms fall off.

“This year I’ll make 50 or 75.”

When Dean got involved in the prep, as it turns out, they are as much a Jola and Dean partnership in the kitchen as in the business, the dough for the pierogi and uszka took a new turn. He went off and bought something they both say would have Jola’s father turning in his grave: a pasta maker. The sort you run your dough through to make your home-made Italian pasta.

“We still do the mixing by hand, but it means we no longer have to do all that rolling…” The circles of dough that get filled, then folded over and crimped, are cut with an overturned glass. And it’s a joint effort.

When I arrive for what is a belated Durban-style Polish Christmas, where we actually sit down the day after Christmas with a couple of friends, also a legacy of the Polish children of Oudtshoorn, I see that Dean has far more strings to his bow than electrical compliance… It is he who is at the stove, turning the day-before-Christmas frozen pierogi into succulent, lightly crisped and luscious delights, which he delivers, perfection on a plate, in relays, so we can add the cream and while Danuta dozes off after her light light lunch in the adjoining room, sit and chat and enjoy her legacy in the form of a perfectly modern South African Polish table. DM

See the Polish orphans of Oudtshoorn story on Origins 22: Genealogy and History.

See: Where to find the best Polish recipes in English

Follow Wanda Hennig on Instagram

Polish traditions live on for Danuta Miloszewski, pictured in April 2025 and on her wedding day in 1951. Christmas pierogi adapted from a Kuchnia Polska recipe. Catholic ‘wafers’ for ‘wigilia’ dinner. (Photos and collage: Wanda Hennig)

Polish traditions live on for Danuta Miloszewski, pictured in April 2025 and on her wedding day in 1951. Christmas pierogi adapted from a Kuchnia Polska recipe. Catholic ‘wafers’ for ‘wigilia’ dinner. (Photos and collage: Wanda Hennig)