When South Africa assumed the presidency of the G20, few expected the gathering to become a quiet geopolitical milestone. Most anticipated the usual choreography of declarations, group photographs and diplomatic gestures. What unfolded, however, was far more consequential. The United States chose not to participate. It insisted, publicly and privately, that under these circumstances a Leaders’ Declaration could not, or should not, be adopted. And yet, under South Africa’s stewardship, the declaration was adopted, unanimously and without objection from those present.

For the first time in the G20’s history, the world reached consensus without the United States. No walkouts. No protests. No sense of crisis. Just a group of nations negotiating on their own terms and finalising a collective position.

A small procedural moment? Perhaps. But as history often reminds us, inflection points do not always arrive trumpeting their significance. Sometimes they slip quietly into the record. And one day, analysts may look back on this gathering as the moment the world discovered that it could, quite simply, act without Washington.

This was not rebellion. Nobody was trying to exclude the US, humiliate it, or forge an anti-American bloc. Instead, something more revealing occurred: the world behaved as if the US were no longer the axis around which global decision-making must revolve. The machinery of global governance creaked forward, and the absence of the US didn’t stop it. It didn’t even slow it down.

For a world that has, for nearly eight decades, been conditioned to believe that the United States is indispensable, this was a profound psychological shift.

A widening fault line on economic strategy

The South African G20 also exposed something else: the unmistakable divergence between US global economic thinking and that of most other major powers. Washington has spent the past several years urging partners to “de-risk” from China, often a diplomatic euphemism for a more fundamental strategic decoupling. But outside Washington’s immediate orbit, enthusiasm for this agenda is scant.

European leaders, facing the hard mathematical realities of their economies, have repeated the same refrain: de-risking is acceptable, but decoupling is impossible. India, the supposed rival to China, has stayed firmly committed to strategic autonomy and refuses to choose sides. Indonesia, Brazil, South Africa, the African Union and the vast majority of the Global South see decoupling not as a strategic necessity, but as an economic hazard.

Their message is consistent: development requires integration, not fragmentation. Supply chains must diversify, not divide. The world economy cannot afford a binary structure designed within the walls of Washington’s geopolitical anxieties.

Thus, when the G20 gathered in South Africa, the US narrative on economic separation found few takers. If anything, the mood favoured the opposite: a reaffirmation of interconnectedness. The rest of the world simply does not want the ideological and economic straightjacket of a new Cold War.

The numbers tell an even richer story

The reason Washington’s absence did not derail the talks may lie in the shifting weight of the global economy itself.

The US remains the world’s largest single economy, but the G20 minus the US forms a combined economic bloc almost three times larger. In population terms, the difference is staggering: roughly 340 million Americans compared to nearly 5.8 billion others represented at the table. China alone now dominates global manufacturing. India’s demographic and economic growth continues its upward march. The European Union still commands enormous market power. The Gulf, Asean (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), Latin America and Africa are emerging as unmistakable engines of demand.

Where the US remains truly dominant is in finance. The dollar is still the backbone of global reserves. US capital markets remain unmatched in depth. US sanctions, routed through the dollar system, continue to carry real weight. But hegemony built on finance alone is profoundly vulnerable. If the world starts systematically insulating itself from US leverage, diversifying reserves, adopting alternative payment systems and building regional banks, the long-term trajectory becomes obvious.

You do not need to dethrone the dollar to weaken it. You only need to use it less. And that is precisely what many countries have been quietly doing.

Washington’s instinctive answer: more pressure

What happens if the US realises that the world is no longer orbiting it automatically? Recent history offers a clue. Over the past decade, Washington has relied increasingly on coercive unilateralism: secondary sanctions, threats of market exclusion, extraterritorial regulation, export controls, a punitive tariff regime and political pressure to force alignment.

It is a strategy that works, until it doesn’t.

In the short term, coercion produces results. Banks fold under pressure. Corporations adjust supply chains. Governments soften their positions.

But as a long-term strategy, coercive unilateralism is a slow-moving disaster for US influence.

Middle powers, India, Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, begin quietly reorganising their economic and diplomatic architecture to reduce exposure to US pressure. Global South blocs grow more cohesive, because they now share a common concern: how to insulate themselves from Washington’s punitive reach. Even US allies become uneasy. Europe does not want decoupling. Japan and South Korea rely on Chinese markets. African nations are unwilling to be lectured into geopolitical camps.

Instead of strengthening its leadership, coercion erodes it.

The paradox of hegemonic overreach

Here lies the geopolitical paradox of our era: the more Washington tries to preserve its influence through pressure, the more it accelerates the erosion of that influence.

- Every sanction pushes countries to build alternatives.

- Every export ban spurs investment in competing technologies.

- Every act of unilateral punishment validates the case for multipolarity.

- Every diplomatic ultimatum deepens the instinct for hedging.

Coercive unilateralism teaches the world one lesson repeatedly: never be dependent on the US.

This is not what leadership looks like. It is what insecurity looks like.

A world moving on with confidence

The South African G20 presidency revealed that the world is not moving against the US. It is moving without the US and doing so without drama, without ideology, and without fear. This is precisely what multipolarity looks like in practice: a quiet normalisation of autonomy.

The rest of the world still sees value in the US. It still wants partnership, innovation and cooperation. But it no longer assumes that global consensus requires Washington’s blessing. And that, in geopolitical terms, is the threshold between hegemony and post-hegemony.

The US is not being rejected. It is being bypassed.

Whether Washington recognises this and recalibrates, or doubles down on coercive unilateralism, will determine the character of the coming international order. If it adopts cooperation over compulsion, it can remain a central, constructive pillar of global governance. If it chooses punishment over partnership, it will increasingly find itself standing alone while others quietly build a world designed to function without it.

The South African G20 meeting was not a confrontation. It was a revelation. And the revelation was simple: the world is learning to move on. DM

Daryl Swanepoel is the CEO of the Inclusive Society Institute, a South African think tank dedicated to advancing evidence-based public policy, strengthening democratic governance, and contributing African perspectives to the evolving global multilateral order.

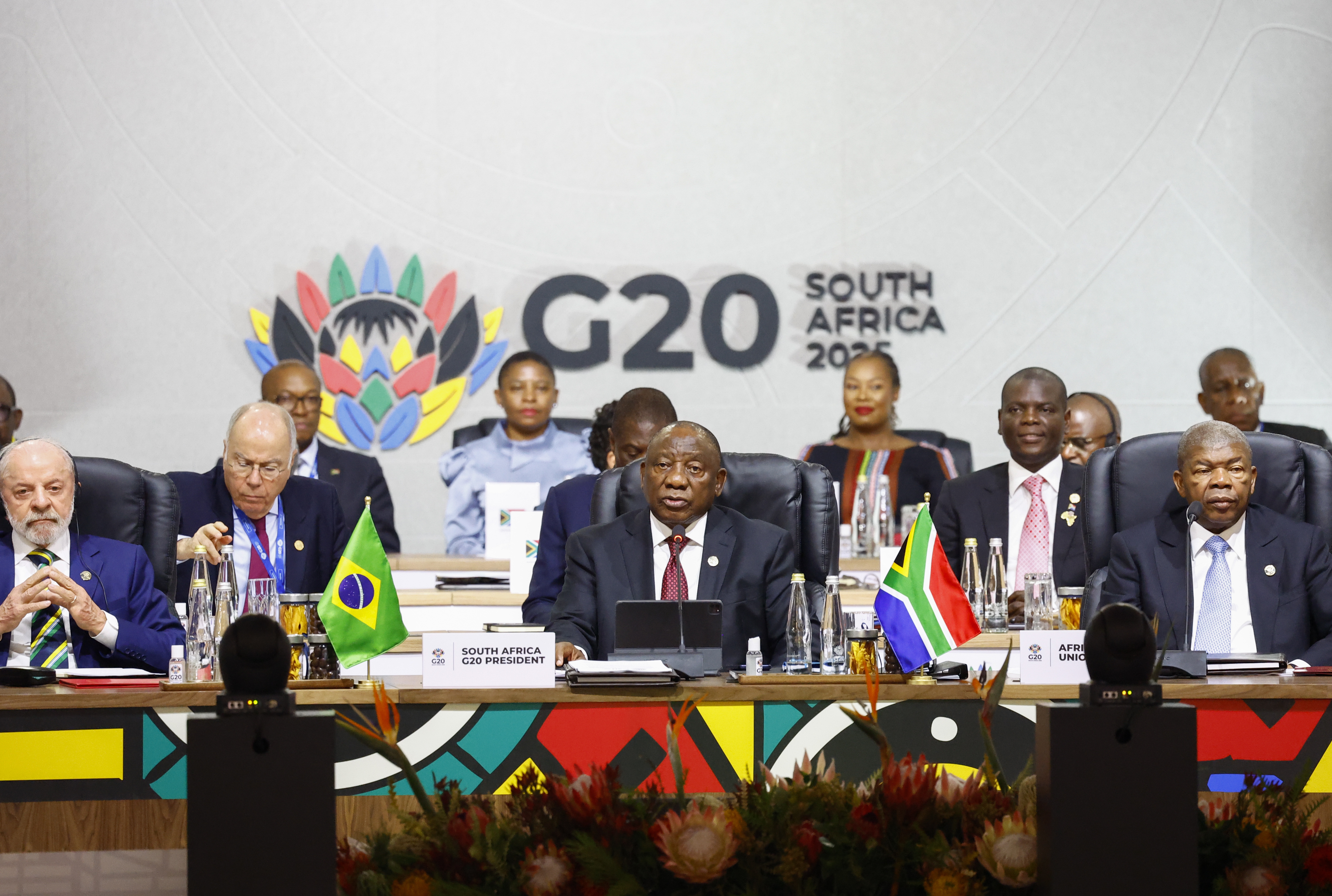

President Cyril Ramaphosa speaks at a plenary session on the opening day of the G20 Summit at the Nasrec Expo Centre in Johannesburg on 22 November. (Photo: Thomas Mukoya / Pool /EPA)

President Cyril Ramaphosa speaks at a plenary session on the opening day of the G20 Summit at the Nasrec Expo Centre in Johannesburg on 22 November. (Photo: Thomas Mukoya / Pool /EPA)