My sister and I were very nearly brought up Chinese. But for a decision that took barely seconds, I could have been born in Hong Kong. But there were two options on the table that grey winter’s day in Yorkshire in 1952 when my dad told my mom he had to live in a hot climate. The other choice: Oranjemund, a dusty diamond mining town in the bottom left hand corner of what was then South West Africa.

They already had two children, but not me. My sister Pat was meant to be known as Gloria, which is in fact her first name. Gloria Patricia Jackman. But, the first day our mother Betty Jackman strolled down the High Street in Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire, a tall, buxom woman asked what the “bairn’s” name was. On hearing her name, she threw her arms in the air and yelled “Gloriallelujah!” while everyone in the street stared.

She was Pat from that moment onwards.

Funny, that. My first name is Charles. Born in Oranjemund in April 1955, the night after my birth my parents had a discussion about whether I’d be Anthony Charles or Charles Anthony. My mom won the argument — I’d be Anthony Charles, the second being my dad’s eldest brother’s first name.

But it was my dad who went to register me and when the moment came, he couldn’t stop himself. I only found out when I was 20 and ordered a copy of my birth certificate. Charles Anthony Jackman… I was amazed. Even my signature is still AC Jackman.

What would these Yorkshire folk have made of Hong Kong cuisine? All that garlic and chilli. No mushy peas. Then again, of course, Hong Kong was half British (until 1997) so there would have been plenty of recognisable food on some menus. I suppose our dad Cyril Jackman may have eaten local fare when his ship was in port in Shanghai, Hong Kong and elsewhere in the East, but there’s no memory of anything remotely eastern in his cooking in our Oranjemund years.

/file/attachments/2984/pat-goldenhair_275014_1c137bf94b4c76d3278641bd53de02c9.jpg)

The family that left Cleckheaton in December 1952 to get the boat train to Southampton via London comprised Betty, Cyril, Pat (then nearly 3) and Phillip (an infant only a few months old). The fare on board Edinburgh Castle would have pleased them, all very British. A menu from 1956 — it wouldn’t have been much changed — offers consommé Julienne (clear soup with julienne vegetables), poached Cape Fillets Joinville (a sauce of shrimps, mushrooms and truffle), steak and kidney pudding, and a cold buffet of Cumberland ham, pressed pork, and pâté Edinburgh, a farmhouse-style spread.

Mom and dad used to talk about the crossing of the Equator mid-journey, a scene of revelry and a fair bit of elbow-bending. Our parents enjoyed a tipple — in fact, they’d met in a pub soon after my dad had returned from his war time service in the Royal Navy, and mom from the Land Army, stationed in Wales, a time she loved “to bits” as she always said.

The dish that leaps out at me on that shipboard menu is steak and kidney pudding. Oranjemund was in part a town of British émigrés, and the grocery store used to order sizeable tins of steak and kidney pudding, enough to feed a family with mashed potatoes and peas on the side. It had a suet pastry, and the “pudding” was steamed for hours before it was turned out. In British home kitchens, it would have been made in a pudding bowl immersed in simmering water with the steam rising to the lid and cooking the contents.

/file/attachments/2984/pat-tony-betty1_711719_09954e2c30cb2cc8fc4c39b37e34c440.jpg)

Mom had been very worried about what it would be like living in a diamond mining town somewhere in Africa. When the ship docked in Cape Town, she breathed a huge sigh of relief and said — well, this looks alright!

Then they were taken to the airport where they boarded a little Skymaster to fly to the airport at the mouth of the Orange River. They boarded a little bus which drove to town and all the way through to the house at the furthest end. Number 38, 13th avenue.

The house was made of large cement bricks, which hadn’t been painted yet. There was no fence, just hard semi-desert ground. As the bus drove off and the dust settled around them, two parents and their small children, Betty Jackman sat on a suitcase and said, “Cyril, I’m not goin’ in. Because if I go in, we’ll have to stay.” She went in.

By the time I came along in April 1955, dad was well settled into his job as a fitter and turner at one of the plants of the alluvial mining operations. I don’t know if mom had started working in the grocery store yet but she would later spend many happy years as a cashier, chatting to everyone in town. She was very popular, and great fun at a party. They’d go to the “Rec Club” several times a week and come home very noisily. Pat told me years later that she would babysit me often.

Throughout those 17 years, I watched my mom cook in the kitchen and sometimes my dad. I learnt to cook a few things myself, especially sweet things such as pink-and-white coconut ice, toffee, cakes and even had a go at Sunday roasts.

In late March 1958, when I was a month short of three, Phillip set off for his Sunday school teacher’s house on the bicycle he’d been given for Christmas. On the street corners before main intersections there were a series of bollards between the house and the tarred road. Phillip aimed between two of these and misjudged. The cycle hit a bollard, he went over, and his head connected with something very hard. He died of a brain haemorrhage in the Oranjemund hospital that evening at six o’clock. (To use the terminology of the time.)

He lies there now, a tiny grave with a headstone missing the angel that was stolen somewhere along the way. I visited Oranjemund in June 2018 for the first time since we left there in June 1969. At his graveside, I was awash with emotion and regret that I didn’t know him, couldn’t imagine what he might have been like as an adult and a big brother. I commune with him at times, when I’m alone and the aura of the poet envelops me.

When I was in Sub A at Oranjemund Primary, Pat was in Standard 5. But in 1961 she was enrolled at Good Hope Seminary in Cape Town. There was no high school in Oranjemund and the kids would be flown to and from Cape Town at the beginning and end of every term.

We’d only see each other in the school holidays, and Pat would spend most of her days in the Belelie family’s house across the road, with her best friend Cathy. Danny, the second youngest of the seven Belelie kids, was my friend and we’d play in their sandpit. Mrs Belelie would often come out with “the strap”, threatening to beat the living daylights out of him if he didn’t stop doing whatever was annoying her. She was annoyed a lot.

Pat loved making her own clothes, which became a lifelong hobby. My niece, Nikki, inherited this habit and is so good at it that she’s planning a clothing line.

But from that moment on, when she started boarding school 700 miles away, Pat and I lived in different places for most of our lives. I’d always visit whenever I could, and we always stayed in touch. It was only in 1969, when Consolidated Diamond Mines fired Cyril Jackman for his drinking on the job, that Pat and I were to spend time in the same city, though only until the following April, when she and Gerry moved to Durban.

/file/attachments/2984/pat-hair_767376_29fcd47e8aa4d68e266f7b68e71eaf79.jpg)

Gerry. That’s a very important name in my life. In the mid Sixties, Pat was in the lounge — it must have been the school holidays — lying down poring over two teen magazines, Jackie and Debonair. On a righthand page of one of them were the listings of pen pals, much like classified ads. She circled three of them. One was Gerald Francis Kuhn of Mountain Top farm, Cathcart. Interests included commercial art, guitar, and folk music.

Off she went to Cape Town and next thing we knew, here she was in Oranjemund for Christmas with her boyfriend. Gerry Kuhn, the first male in Oranjemund to wear bellbottomed jeans. He was a draftsman by then, and was to become a civil engineer specialising in mine ventilation, and later an architect as well. He is the most talented human I know (inexplicably, he says the same of me), and we’ve both met Prince Charles, long before he was king.

Soon after they moved into Number 6 Wildhaus in Milnerton north in 1969, we arrived and stayed in the Cambridge Hotel, because it was nearby. I listened to the moon landing on a transistor radio in my room.

Gerry played a huge role in the aftermath of dad’s firing, when he couldn’t hold down a job on a freighter for more than two weeks, when all of our household goods went on auction for a pittance, and when he went to court on mom’s behalf to have dad committed to a recovery home for alcoholics. Gery was and is the most amazing human being I know.

None of them knew about my truancy in 1970 when I didn’t go to school on the first day of term in January, and they only caught up with me in August. But he would have helped me if I’d told him. With hindsight I should have, but I was too wrapped up in hiding and trying to find the courage to stow away on a Union Castle ship to England to even think about asking an adult for help.

After a year in Durban, Pat and Gerry moved to Ulco, a tiny place of cement dust in the northern Cape, then to Kimberley for many years and on to Joburg where Gerry was a diamond in the Anglo American firmament. Ultimately they moved to Piketberg, on the edge of the Sandveld, where Gerry turned one of his inventions (he’s one of those too), the DustWatch, into a business.

Pat became their office administrator and accountant, and I would visit when I could, even when my Cape Town newspaper job became really demanding in the Nineties — what I had thought were my halcyon newspaper days until Daily Maverick came along 11 years ago.

All through those years, whether Durban, Ulco, Kimberley, Johannesburg or Piketberg, I knew all of their homes, their dogs (especially lanky Judy, who loved me), and would stay in their spare room. In the morning, there’d be a knock on the bedroom door and it would be Pat bearing two mugs of coffee.

She’d stand in the doorway or sit on the edge of the bed and we’d talk and talk and talk. She was always a great conversationalist.

And this was the worst thing about the dementia that came down on her like a bell jar a few years ago — Gerry and I have been trying to pinpoint when it was. Her conversation became awkward as she paused and stared, trying to remember things and the words with which to express them.

I started visiting Piketberg much more often than before, even though we lived across the country. Yet, even after 15 or so minutes there, it would be hard to look at her, because it was so hard to see this version of her, knowing who she was inside. Gerry and I grew accustomed to repeating things over and over and over, and both decided that, each time, we would answer her as if she had asked it the first time. Because, to her, that’s how it was.

One by one words drifted away from her, until the only word she really knew was love. She’d grab hold of me on my visits over the past three years and say, “Tony, I LOVE you!” with tears streaming down her cheeks. It was lovely and awful at the same time.

In the end, Gerry and I both hoped that she would precede him — not because we wanted her to go, but because the thought of her being left behind without Gerry was unthinkable. (She died at 76, he is 79.) She would not have been able to cope without the man who had been at her side since June 1967, when they married at St James Church in Sea Point. That’s 57 years, and it ended at 12.20pm on Monday, 3 November 2025 — the day after what would have been our mother Betty’s 101st birthday.

/file/attachments/2984/pat-jackman_324180_cc0f20d1118c0533638788cdfad6f183.jpg)

During the planning of her funeral last week, Gerry and I delved deeply into her dementia and its scale. It was my memories of those morning coffee conversations in Kimberley and beyond that made us both realise just how much had been lost, and over how much time. Even 15 years ago, our chats were nothing like they had once been, and we realise now that this thing had been creeping up on her, incrementally, for a very long time.

I would like to have my sister back, the one I knew. Pat Jackman (later Pat Kuhn) with her long golden hair, her paisley mini dresses and those hot pants that everyone in Oranjemund gossiped about in the Sixties. The Pat who went with Gerry to the (now notorious) Navigator’s Den nightclub in Cape Town in that psychedelic decade, where a galleon had been built from the ground floor all the way up to the top floor by… Gerry Kuhn. Yes, my boet Gerry built that.

Pat the mother to Richard and Niks, the grandma to Amy-Grace and Matthew, aunt to Rebecca and Jessica and so many more on the Kuhn side. Pat the daughter of Cyril and Betty Jackman of Cleckheaten, West Yorkshire. Pat, my sister. I love you.

Coda

Gerry and I want to take an old boys’ trip to Oranjemund, and go to Phillip’s graveside. We’ll peer over the fence of 38, 13th Avenue and wonder where the orchard and vegetable gardens went. We’ll marvel at the palm tree mom planted, now five storeys high. We will see ourselves there in the 60s, me in my blue denim jacket (even then), Gerry in his bellbottoms, and Pat in her paisley dress. We’ll imagine ourselves inside the house, long ago.

Maybe Pat will be talking to Phillip, in his bedroom, over cups of coffee. DM

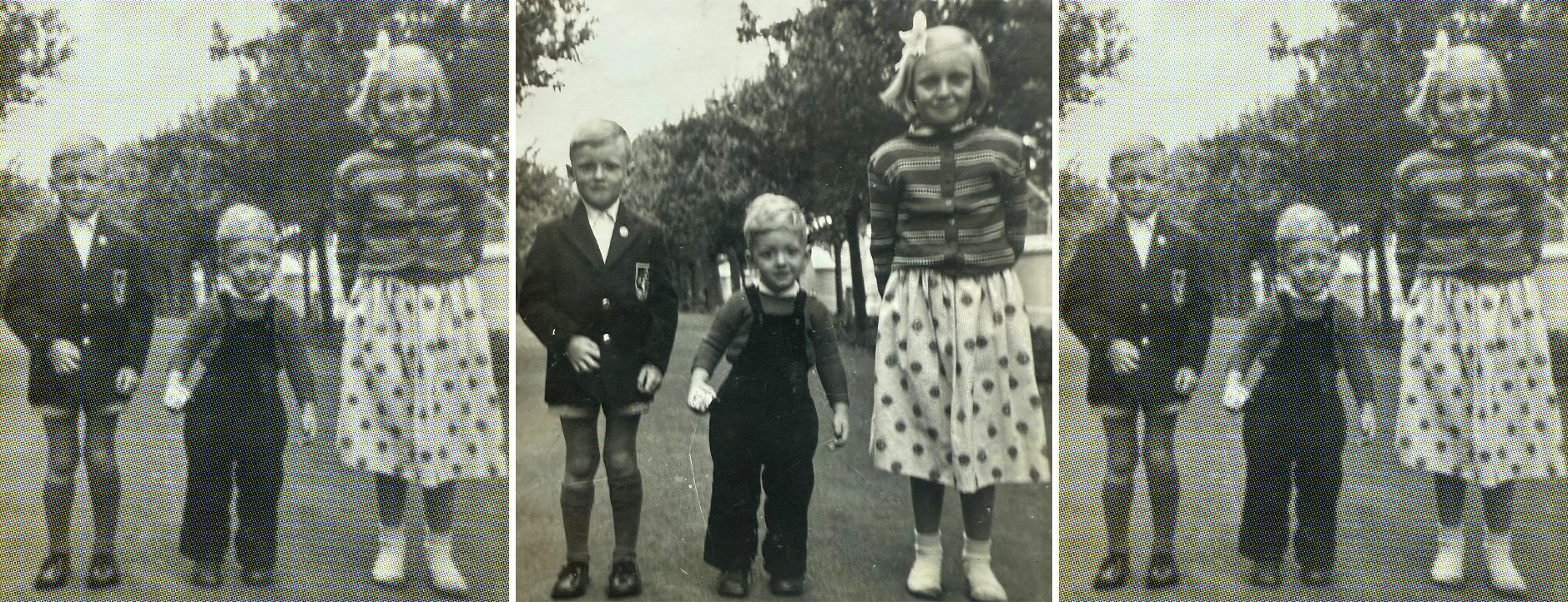

Phillip, Tony and Pat Jackman in the Company’s Garden, January 1958. Phillip was to die in a bicycle accident two months later. (Photo: Cyril Jackman)

Phillip, Tony and Pat Jackman in the Company’s Garden, January 1958. Phillip was to die in a bicycle accident two months later. (Photo: Cyril Jackman)