On 22 September 2025, Riek Machar, the suspended First Vice-President of South Sudan and leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition, appeared before a special court in Juba.

His arrest on 11 September, along with seven colleagues, dealt the country’s peace accord a blow that could prove fatal. Charges include murder, crimes against humanity and treason.

The arraignment reflects President Salva Kiir Mayardit’s approach to governance, characterised by frequent dismissals of senior government officials and his own brand of lawfare.

Although South Sudan’s peace agreement hasn’t formally collapsed, repeated hits have undermined its legitimacy. Stakeholders in the diplomatic community, opposition groups and civil society are divided over its relevance.

Some, like Machar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition faction led by party chairperson Nathaniel Oyet, say the 2018 Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan died long ago. Others are hesitant to go that far, fearing they’ll lose the central, if not only, reference point for peace in South Sudan.

Whether alive or not, many still view the peace agreement as symbolically important, as it has offered relative stability for eight years.

In reality, the power-sharing agreement holding the government of South Sudan together has been steadily unravelling, undermined by repeated delays in elections, unilateral decision-making within a supposedly unified government, and a bungled security sector reform process. These shortcomings have drained the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan’s vitality.

Ironically, the agreement sowed the seeds of its own downfall. By removing key decision-making safeguards built into the earlier 2015 peace agreement, it has become little more than a tool to appease or control dissatisfied opposition groups. It has also relied too heavily on Kiir and Machar, whose disagreements predate the agreement, perpetuating mistrust and eroding the essence of compromise in the agreement.

Agreement violated

In 2023, Kiir dismissed Defence Minister Angelina Teny and unilaterally transferred the Defence Ministry from Machar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition to Kiir’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Government. The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition and Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission condemned this act. It not only violated the agreement but also underscored the fragility of the Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity.

By early 2025, South Sudan faced a crisis. Violence erupted in Nasir in March, followed by Machar’s arrest, along with several top Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition leaders. Some went into exile, while senior party figures such as Stephen Par Kuol aligned with the government — which a Juba analyst who requested anonymity described as a move to keep Nuer influence in the unity government.

The Reconstituted Joint Monitoring and Evaluation Commission condemned Machar’s arrest as a setback. At the same time, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development, one of the agreement’s guarantors, warned that “these developments seriously undermine the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan and risk plunging the country back into violent conflict”.

South Sudan now faces an economic crisis, worsened by disrupted oil production — its primary source of revenue — due to the conflict in Sudan. Combined with sporadic outbreaks of violence in various parts of the country, the agreement is now paralysed. The institutions tasked with implementing the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan, including the Council of Ministers, Transitional National Legislature, Joint Defence Board, and Joint Verification and Monitoring Mechanism, are effectively inoperative. The agreement has effectively been “abrogated”, according to Oyet.

The exit of one party from the agreement may not automatically render it void, however. In fact, continuing to rely on a tattered agreement might be a pragmatic recognition that the accord, despite flaws, still structures political participation and international cooperation.

Regardless, Kiir’s actions have undermined the agreement’s spirit and purpose — to jointly steer South Sudan towards its national motto of justice, liberty and prosperity. The question of what comes next is now a growing concern, given that Kiir, who has repeatedly flouted the peace deal, seems to be implementing a succession plan.

Succession process?

United States-sanctioned businessman Benjamin Bol Mel’s meteoric rise to vice-president and economic cluster chairperson, and promotion to military general, alongside Kiir’s appointment of his daughter Adut Salva Kiir as senior presidential envoy for special programmes, suggests a succession process.

If true, it would not be a mere act of patronage, but a marker of an informal succession process unfolding outside the Revitalised Agreement for the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan and National Dialogue — the main platforms for fostering political consensus in South Sudan. This has destabilising consequences amid many disgruntled former SPLM-Army officials, non-signatory armed groups, and a generally fragmented government.

For South Sudan to break free from the current deadlock and avoid a relapse into civil war, it must end the fragile transition and move towards an elected government that can tackle state building. This involves recognising that the agreement has been compromised, recalibrating expectations, and paving a new, bold path forward.

Introducing a Tumaini-style process, modelled on Kenya’s Tumaini Initiative, which sought to bring non-signatories and influential figures into an inclusive dialogue framework, would broaden the political landscape beyond SPLM’s Kiir and Machar and reduce the risk of spoilers.

However, this approach has limitations. Many non-signatory armed groups lack sufficient political and military clout to make a significant difference in a new setup, and the country’s future would still depend on the same two leaders, risking a continuation of the same cycle of instability.

The 2020 report of South Sudan’s National Dialogue, established by Kiir in 2017 to address grievances and foster reconciliation, concluded that Machar and Kiir were the main obstacles to peace in the country. Yet their parties remain central to the country’s politics. The challenge is to reconfigure leadership and the peace framework to maintain these blocs while expanding inclusion beyond the current setup.

This approach, which would inevitably be influenced by ethnic politics, would be tough — but not impossible — to initiate. There is already speculation in Juba that Kiir would like to step down from politics, but not without Machar doing the same. New leaders emerging from both the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Government and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition could ensure institutional continuity, reassure the old guard and meet popular demands for change.

South Sudan’s options — whether reinstating Machar, renewing the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Government and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition leaderships without Kiir and Machar, or even following Kiir’s apparent succession path — must follow a clear sequence.

First, stabilising the political, economic and security landscape is crucial. Next comes restoring state authority countrywide. Only then should elections take place, under credible oversight. This sequencing may require yet another extension of the transitional government, which now appears increasingly likely. DM

Moses Chrispus Okello is a Senior Researcher, Institute for Security Studies Addis Ababa, and Dr Ibrahim Sakawa Magara is a PeaceRep Post-Doctoral Research Fellow, Centre for Peace and Security at Coventry University.

First published by ISS Today.

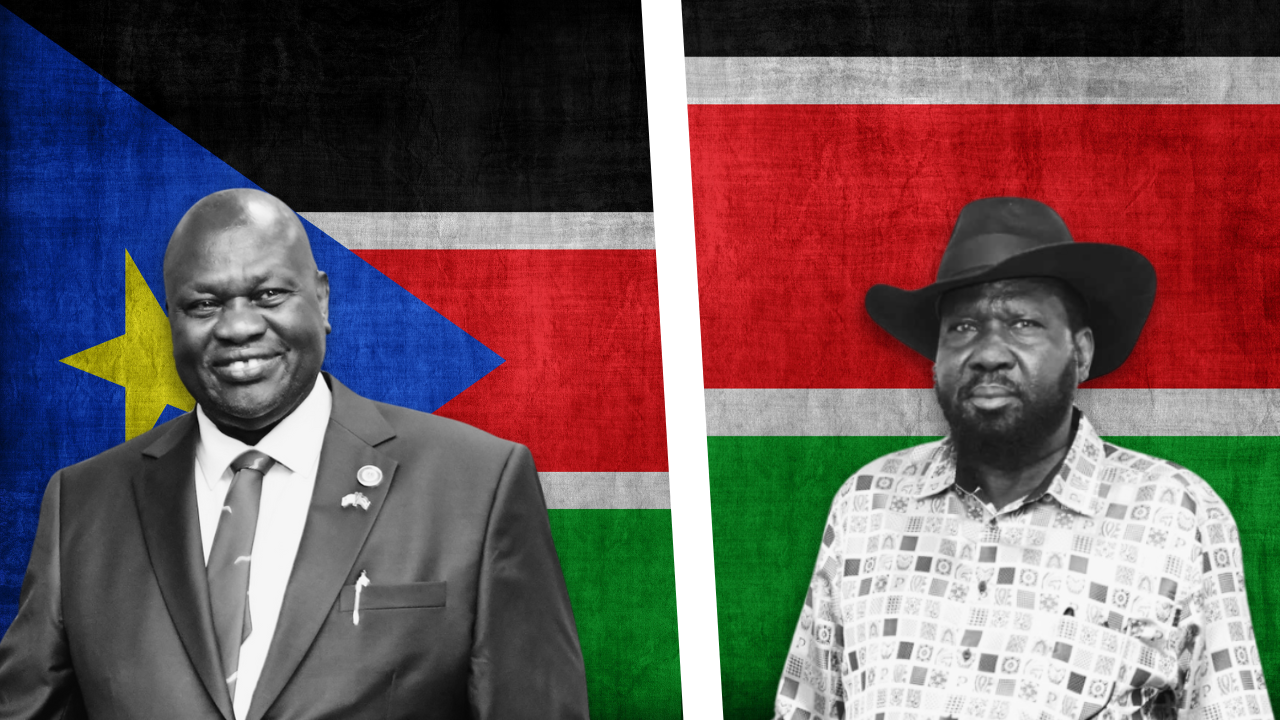

South Sudan President Salva Kiir Mayardit, right, and suspended First Vice-President Riek Machar. (Image: ISS)

South Sudan President Salva Kiir Mayardit, right, and suspended First Vice-President Riek Machar. (Image: ISS)