Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths …

I would spread the cloths under your feet,

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Few can capture the essence of a sociopolitical crisis as pithily as the Irish poet William Butler Yeats – and this, in a few lines. In his 1899 poem, He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven, Yeats deftly “plots” the material and psychological “distance” between the poor and the rich who rule over them.

Ours is a country where the gap between the rich and the poor has not only been growing, but the South African poor have nothing more to give but their fondest dreams – dreams which are being wantonly trampled upon. Resonant with Yeats’s other famous poem, The Second Coming, we have witnessed how, in one short generation (1994-2024), “things” have begun to “fall apart” all around us, as the South African “political centre” seems to be no longer holding.

Thirty-one years later, Nelson Mandela’s 1994 promise of a “triumph in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of the millions of our people” has begun to sound like a farce. Hope is becoming a scarce commodity in South Africa.

For a nation whose economy has been comatose for more than a decade, former president Thabo Mbeki’s emphatic ending of his “I am an African” speech with the words, “nothing can stop us now”, sounds like extreme denialism – 29 years later. Yet it is instructive that Mbeki uttered these words on occasion of the celebration of one of the greatest outcomes of the first National Dialogue – the South African Constitution.

And yet today, the words once spoken by former president Kgalema Motlanthe in his 2008 inaugural speech – that “we remain on course to halve unemployment and poverty by 2014” – sound like a cruel joke.

Seven years later, President Cyril Ramaphosa’s “New Dawn” has yet to dawn. Instead, the Zondo and now the Madlanga commissions, focused on corruption, might define the Ramaphosa presidency.

A different type of a ‘New Dawn’

For their part, the South African electorate has ushered in a different kind of “New Dawn” – a citizen-led new dawn that has brought the country to a Francis Fukuyama-like “end-of-history” moment. That is, the end of history as we have known it for the past 30 years. In this end-of-history kind of new dawn, the significance of individual political parties has been greatly reduced, dealing a heavy blow to several political egos in the process.

When several media houses at home and abroad asked Mbeki for his evaluation and commentary on the 30 years of democracy in South Africa, his eventual “response” was to propose a South African National Dialogue. Perhaps Mbeki realised instinctively that the historic elections of 2024 – in which his own political party lost its 30-year majority – were both a form and an outcome of a latent national dialogue, between citizens about their country and its future.

More importantly, both Mbeki and Ramaphosa are of the view that the National Dialogue is the only way forward for South Africa – a democratic country born of a “national dialogue” in which both of them were deeply involved.

We need to talk

In his capacity as head of state, Ramaphosa rightfully performed his constitutional duty when he announced and convened the National Dialogue. His announcement resonated with many South Africans, from Musina to Cape Town.

And yet, such is the current political atmosphere that the political long knives are frequently constantly polished and brandished – inside the Government of National Unity. As we move towards the local elections (2026), the low trust between government and citizens, political parties and citizens as well as between politicians and citizens in general will become more acute.

It is remarkable that, amid this scepticism and low trust, South Africans agree about one thing – the need for a National Dialogue – and for the process to be radically inclusive, transparent and credible.

Inevitably, some of the general cynicism of our times has spilled into the necessarily animated discussions about the National Dialogue. It cannot be ruled out that some of the “dissent” may be “manufactured” by those who are either driven by the WIIFM (what’s-in-it-for-me) ethic or the need to grandstand. Such are the TikTok times we live in.

Both those who embrace and those who claim not to embrace the National Dialogue tend to generally agree that there are many challenges facing our nation at this time.

Ironically those who suggest dialogue must be dumped in favour of action (as if dialogue is not a form of action in itself) often expect someone other than themselves to take the necessary action. Usually, they expect the same government that has, for a long time, failed to act to now, all of a sudden, take the necessary action – without first making the effort to understand why and how the government has failed to take action for the past 30 years. Such blind faith in government masquerading as radicalism would be laughable if it were not so tragic.

A presumptuous refrain

The rather presumptuous refrain from the side of some detractors is the suggestion that (because) we “know” the problems, there’s no need to have a National Dialogue. Apart from the faulty epistemology (theory of knowledge) built into this massive presumption – for what does it mean/take to (really) “know” the problems – it is simply not true that the elite, the “leaders”, the middle classes, the chattering classes, the self-appointed “super citizens” and their haughty organisations, or the “educated” who speak “good” English are either capable of or amenable to truly and fully “knowing” the problems of the Yeatsian poor whose dreams are being trampled upon by the very elite classes to which the “know-it-alls” belong.

Worse than the epistemological presumption is the ease and speed with which the elite assume the right and ability to represent and to speak on behalf of the poor and marginalised. This posture smacks of a deep-seated, mostly unconscious, phobia of vertical dialogue between the powerless and the powerful and a basic phobia of hearing ordinary people speak for themselves.

Those who claim to “know” all the problems of all the people in the country also imply that there is no need either for the marginalised to speak or to be listened to. But knowledge of unemployment, crime, suicide, rape statistics, etc, is not knowledge of the conditions in which the victims are languishing, let alone their own views on possible solutions.

Cerebral knowledge of the National Development Plan, the 20-something industrial master plans or the National GBV Strategy must not be confused with a deep understanding of the impact of these, or lack thereof, on ordinary South Africans.

At the end of his recent op-ed on the National Dialogue, University of KwaZulu-Natal professor of geography Brij Maharaj has this to say:

“The National Dialogue 2.0 should not be about saving the ANC. It is about saving our country. All stakeholders must put their shoulders to the wheel, rise above personal, parochial, and party interests, and put South Africa first. In many respects, National Dialogue 2.0 may well be the last throw of the dice.”

With the first national convention behind us, now is the time for ordinary South Africans to ask the politicians, the elites and other members of the ruling classes who, for far too long, have condescendingly claimed to speak for “our people”, “our communities” and “our women”, to stop the charade.

For 30 years, South Africans have “spread their dreams” under the feet of “government” and “state”. It is time we took both our dreams and our country back from the government and from the elites. For the sake of the next generation, let us join hands and use the National Dialogue to craft a strong social compact on the basis of which we will construct a better developmental trajectory of our country. DM

Tinyiko Maluleke and Roelf Meyer are co-chairs of the National Dialogue Eminent Persons Group.

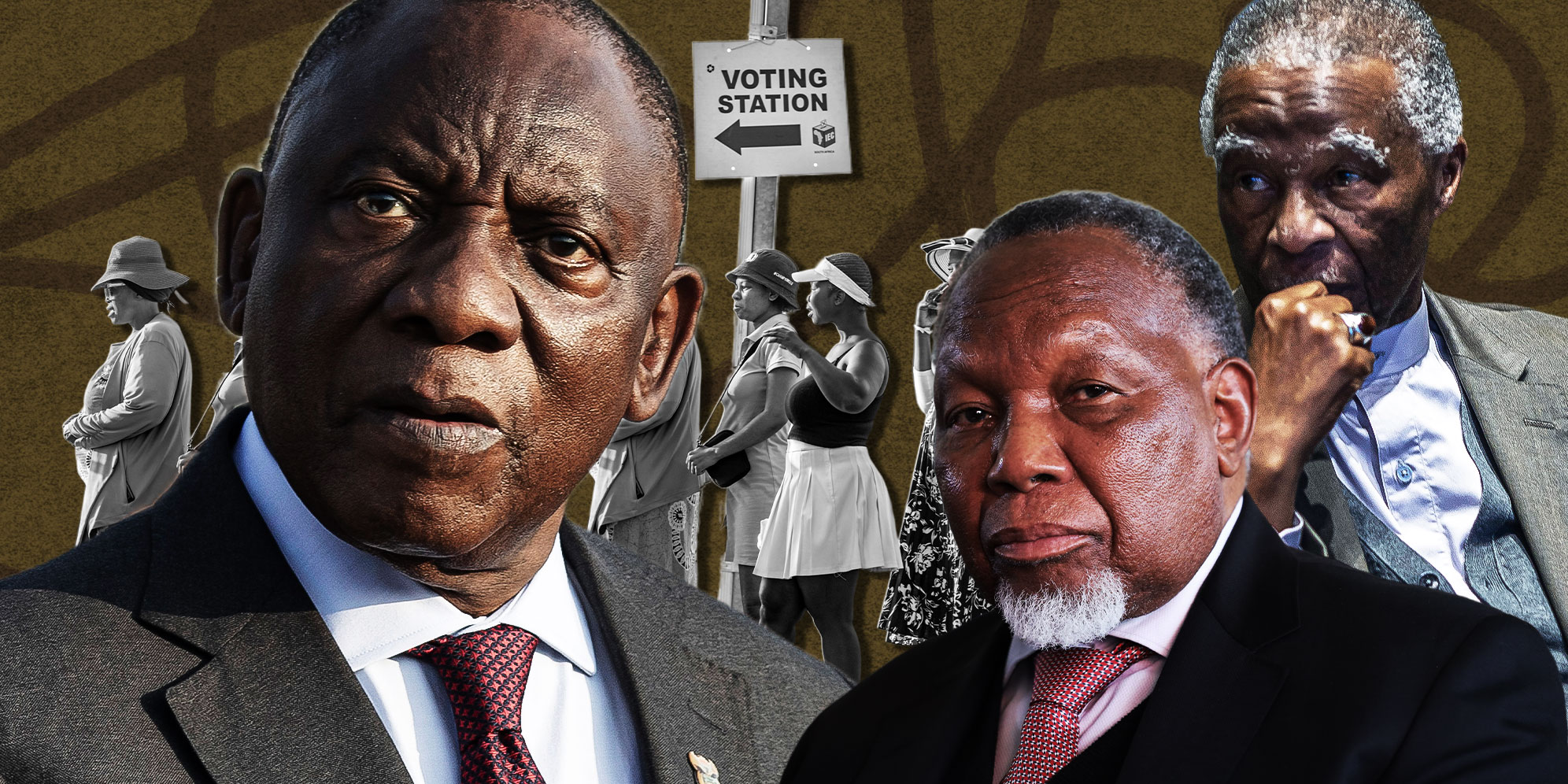

Illustrative Image: President Cyril Ramaphosa (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Gallo Images) | Former president Thabo Mbeki. (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Getty Images) | Former president Kgalema Motlanthe. (Photo: Gallo Images / Luba Lesolle) | People queue to vote. (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Gallo Images)

Illustrative Image: President Cyril Ramaphosa (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Gallo Images) | Former president Thabo Mbeki. (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Getty Images) | Former president Kgalema Motlanthe. (Photo: Gallo Images / Luba Lesolle) | People queue to vote. (Photo: Per-Anders Pettersson / Gallo Images)