The Trump administration wants to take away citizenship from naturalised Americans on a massive scale. Although a recent US Justice Department memo prioritises national security cases, it directs employees to “maximally pursue denaturalisation proceedings in all cases permitted by law and supported by the evidence” across 10 broad priority categories.

Denaturalisation is different from deportation, which removes non-citizens from the country. With civil denaturalisation, the government files a lawsuit to strip people’s US citizenship after they have become citizens, turning them back into non-citizens who can then be deported.

The government can only do this in specific situations. It must prove someone “illegally procured” citizenship by not meeting the requirements, or that they lied or hid important facts during the citizenship process.

The Trump administration’s “maximal enforcement” approach means pursuing any case where evidence might support taking away citizenship, regardless of priority level or strength of evidence. As our earlier research documented, this has already led to cases like that of Baljinder Singh, whose citizenship was revoked based on a name discrepancy that could easily have resulted from a translator’s error rather than intentional fraud.

A brief history

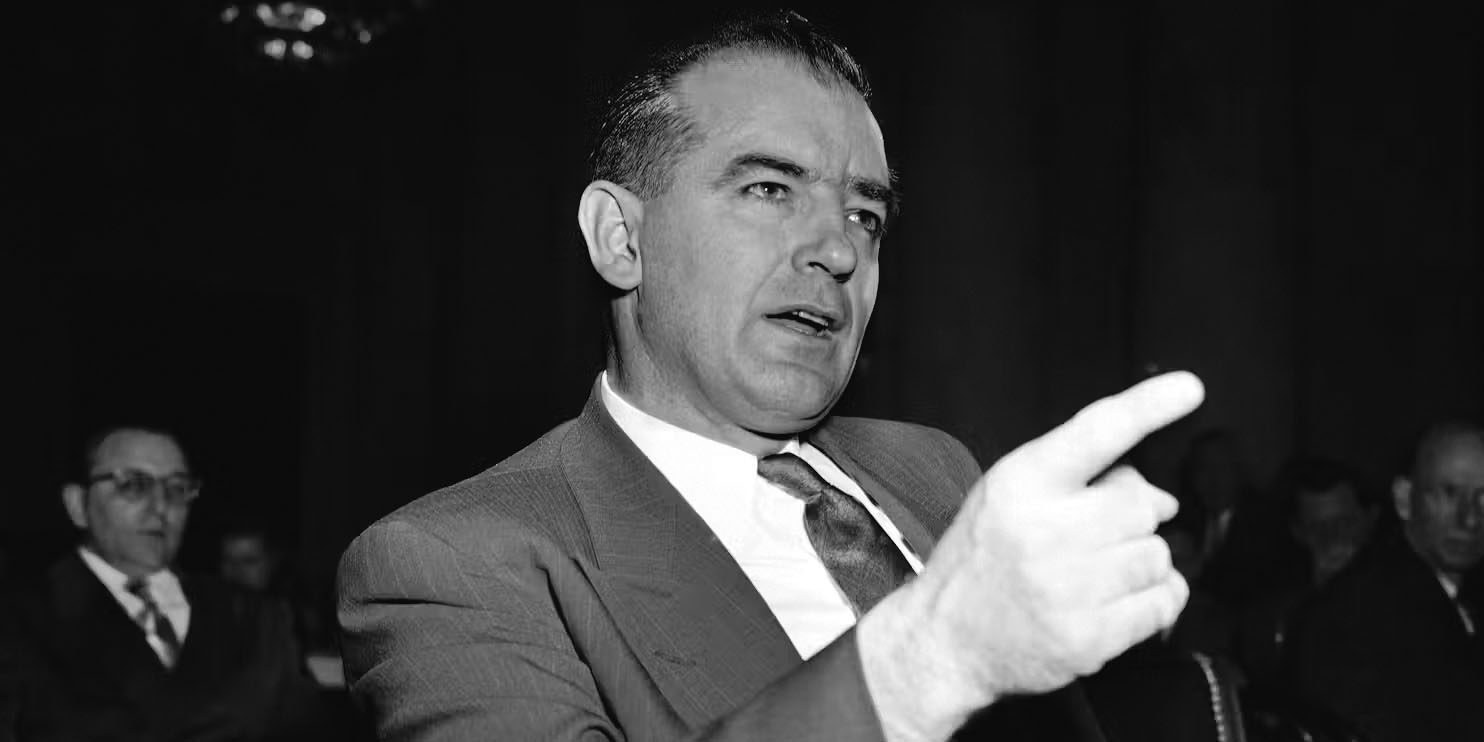

For most of American history, taking away citizenship has been rare. But it increased dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s during the Red Scare period characterised by intense suspicion of communism. The US government targeted people it thought were communists or Nazi supporters. Between 1907 and 1967, more than 22,000 Americans lost their citizenship this way.

Everything changed in 1967 when the Supreme Court decided Afroyim v Rusk. The court said the government usually cannot take away citizenship without the person’s consent. It left open only cases involving fraud during the citizenship process.

After this decision, denaturalisation became extremely rare. From 1968 to 2013, fewer than 150 people lost their citizenship. They were mostly war criminals who had hidden their past.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/GettyImages-2217852297-1.jpg)

How the process works

In criminal lawsuits, defendants get free lawyers if they can’t afford one. They get jury trials. The government must prove guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt” – the highest standard of proof. But in most denaturalisation cases, the government files a civil suit, in which none of these protections exists.

People facing denaturalisation get no free lawyer, meaning poor defendants often face the government alone. There’s no jury trial – just a judge deciding whether someone deserves to remain American. The burden of proof is lower – “clear and convincing evidence” instead of “beyond a reasonable doubt”. Most important, there’s no time limit, so the government can go back decades to build cases.

As law professors who study citizenship, we believe this system violates basic constitutional rights. The Supreme Court has called citizenship a fundamental right. Chief Justice Earl Warren in 1958 described it as the “right to have rights.”

In our reading of the law, taking away such a fundamental right through civil procedures that lack basic constitutional protection – no right to counsel for those who can’t afford it, no jury trial and a lower burden of proof – seems to violate the due process of law required by the constitution.

The bigger problem is what citizenship-stripping policy does to democracy. When the government can strip citizenship from naturalised Americans for decades-old conduct through civil procedures with minimal due process protection – pursuing cases based on evidence that might not meet criminal standards – it undermines the security and permanence that citizenship is supposed to provide.

This creates a system where naturalised citizens face vulnerability that can last their entire lives, potentially chilling their full participation in American democracy.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/12-GettyImages-2181850266.jpg)

The Justice Department memo establishes 10 priority categories for denaturalisation cases. They range from national security threats and war crimes to various forms of fraud, financial crimes and, most importantly, any other cases it deems “sufficiently important to pursue”. This “maximal enforcement” approach means pursuing not just clear cases of fraud, but also any case where evidence might support taking away citizenship, no matter how weak or old the evidence is.

This creates fear throughout immigrant communities. About 20 million naturalised Americans now must worry that any mistake in their decades-old immigration paperwork could cost them their citizenship.

A two-tier system

This policy effectively creates two different types of American citizens. Native-born Americans never have to worry about losing their citizenship, no matter what they do. But naturalised Americans face vulnerability that can last their entire lives.

This has already happened. A woman who became a naturalised citizen in 2007 helped her boss with paperwork that was later used in fraud. She cooperated with the Federal Bureau of Investigation, was characterised by prosecutors as only a “minimal participant”, completed her sentence and still faced losing her citizenship decades later because she didn’t report the crime on her citizenship application – even though she hadn’t been charged at the time.

The Justice Department’s directive to “maximally pursue” cases across 10 broad categories – combined with the first Trump administration’s efforts to review more than 700,000 naturalisation files – represents an unprecedented expansion of denaturalisation efforts.

The policy will almost certainly face legal challenges on constitutional grounds, but the damage may already be done. When naturalised citizens fear that their status could be revoked, it undermines the security and permanence that citizenship is supposed to provide.

The Supreme Court, in Afroyim v Rusk, was focused on protecting existing citizens from losing their citizenship. The constitutional principle behind that decision – that citizenship is a fundamental right that can’t be arbitrarily taken away by whoever happens to be in power – applies equally to how the government handles denaturalisation cases today.

The Trump administration’s directive, combined with court procedures that lack basic constitutional protections, risks creating a system that the Afroyim v Rusk decision sought to prevent – one where, as the Supreme Court said: “A group of citizens temporarily in office can deprive another group of citizens of their citizenship.” DM

First published by The Conversation.

Cassandra Burke Robertson is professor of law and director of the Center for Professional Ethics at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Irina D Manta is professor of law and director of the Center for Intellectual Property Law at Hofstra University in Long Island, New York.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R35.

Senator Joseph McCarthy appears at a March 1950 hearing on charges of communist infiltration at the State Department. (Photo: Herbert K White / AP Photo)

Senator Joseph McCarthy appears at a March 1950 hearing on charges of communist infiltration at the State Department. (Photo: Herbert K White / AP Photo)