Gauteng’s only centralised hub for services to the province’s most vulnerable and special needs children faces shutdown as three provincial departments with overlapping responsibilities appear to be passing the buck on settling debts for unpaid water and electricity bills, paying for building maintenance and dragging their feet to finalise critical lease agreements.

The Children’s Memorial Institute (CMI) has been forced to operate with an intermittent water and electricity supply for more than a year and to shoulder bills the government should be responsible for. According to the CMI there has also been no meaningful engagement with the Gauteng departments of health, education as well as infrastructure and development to break the deadlock and map a way forward.

The CMI board has been forced to use its savings to cover unexpected running costs. But as the months have passed with no resolution, their savings are nearly depleted. Many services offered by the nonprofit and nongovernmental organisations based at the institute have already been scaled back and the future of the institute now hangs in the balance.

The CMI is in Braamfontein, at the bottom of Constitution Hill, and is home to 23 nonprofit organisations (NPOs) and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) which deliver critical services for special needs and vulnerable children. Among them are abused children, children with autism and those who are neurodiverse or have a mental disability. The institute also houses dentistry and counselling services for children. The NPOs based here include Childline, the Teddy Bear Clinic, The Paedodontic Society of South Africa and Autism South Africa.

In 2013, the CMI was formed to create a formalised structure for the various NPOs and NGOs on the campus, many of which are long-established tenants on the campus. The 102-year-old heritage building of the old Transvaal Children’s Hospital is also located here. The formation of the CMI was an intervention at the time to rescue the facility that had faced spiralling neglect for decades. By the mid-1980s many government health units moved out of the Braamfontein site to Johannesburg General Hospital (now Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital) after the hospital opened in 1978.

The exodus left some of the buildings on the Braamfontein site standing empty and poorly maintained. By the late-2000s the old nurses’ residence was illegally occupied and the entire site was at risk of the same fate. The CMI entered into a memorandum of incorporation. This allowed the CMI tenants to use the buildings that are Gauteng Department of Infrastructure and Development (GDID) assets. In turn the CMI, as a collective, would be responsible for rejuvenating the buildings and office spaces and creating a general building fund to cover cleaning, gardening, maintenance and security services. Over the years CMI’s donors have pumped millions into reviving and developing the campus.

The memorandum also set out that payment for water and electricity and the maintenance of lifts would be paid for by Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH). CMJAH’s laundry facilities continue to operate from the CMI campus and is the biggest user of water and electricity on the property.

It was in late 2022, however, that the NGOs on site started running into problems, with the electricity and water supply being cut off. Then came the shock discovery for CMI that there was a whopping R40-million outstanding water bill and an R4-million outstanding electricity bill.

“Only at that point did we find out that the CEO of the CMJAH, Gladys Bogoshi, had since 2018 stopped paying the water and electricity bills despite this being in the memorandum of incorporation,” says Dr Dee Blackie, CEO and creative director of the NGOs Sensory Space and Courage Child Protection & Empowerment. She also serves on the CMI board.

“We still don’t [know] why the CMJAH simply stopped paying and didn’t tell us, leaving us to find out four years later. Despite efforts by the CMI board to engage with Ms Bogoshi she has refused to pay the outstanding amounts, alleging that it should be paid by the NGOs. She has also said she wants nothing to do with us. It must be noted that the NGOs and school sections of the CMI were unoccupied for much of 2020 and 2021 because of the Covid lockdown. However, the hospital laundry worked overtime through this entire period for obvious reasons,” Blackie says.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/AV_00051199.jpg)

More curious woes would come for the CMI board in April 2024, when the biggest tenant in the CMI, the Johannesburg School for Autism, was instructed through the Department of Education to withhold its contributions for services provided from the CMI. Blackie says this resulted in an additional R100,000 deficit per month for running costs. She says the school continues to benefit from many of the services without paying a cent.

In the following month, in May 2024, the CMI called an emergency meeting with the CMJAH, the Gauteng Department of Education’s Mmola Mahlako and the principal of the Johannesburg School for Autism, Simangele Tshabalala. It was at this meeting, Blackie says, that Mahlako announced that the CMI board suddenly was “not recognised” and had no legitimate claim to ask the school to pay for services rendered.

Blackie says the CMI was forced to seek legal opinion to confirm the legitimacy of the memorandum of incorporation and to assert their legal rights to occupy the buildings and receive payments for maintaining the buildings. Blackie says legal opinion seemed to shake the Gauteng Department of Infrastructure and Development (GDID) into action. The GDID put forward the suggestion to draw up separate lease agreements for each NGO, also for GDID to install separate water and electricity meters to enable separate billing. While the CMI completed the paperwork required by GDID’s deadline in November 2024 for this to happen, by July this year there had been no progress, Blackie says.

Blackie says: “It is a unique thing to have all these NPOs on one site in the city as CMI, it should be a jewel for the city. We went from a building that was less than 50% habitable to 100% habitable, and we’ve created a thriving community hub. Many children come here from Hillbrow and the rest of the inner city because they know it’s a safe space. Many of them have faced violence, trauma and abuse. For me what is happening now, with the departments failing to do their job and to take responsibility, is further abuse of the most vulnerable of vulnerable children.”

Blackie adds that the pressure that the CMI is facing is more of the government actively defunding NGOs. This is despite the fact that they are doing the work the government should be doing, she says. Just a year ago, Gauteng premier Panyaza Lesufi had to apologise to NGOs for “recent non-payment of subsidies and funding to the sector”. In the provincial media release at the time, he was quoted as saying: “Our relationship with NGOs is of utmost importance. Unfortunately, there were serious missteps [the delayed payments], and we need to rectify this. Our NGOs are doing invaluable work on behalf of government, and they must be treated with the utmost respect. They are not doing us a favour.”

Blackie says Lesufi’s words don’t square with the attitudes of government officials that she says have adopted an adversarial, hostile and non-productive working relationship with the CMI.

“We are absolutely being ghosted – there’s no open communication or engagement and we’re simply left in the dark as the CMI faces being shut down,” she says.

Claudine Ribeiro is director of the Johannesburg Parent and Child Counselling Centre (JPCCC), which has been in existence for 80 years. It has been part of the CMI from when it was formed in 2013. Ribeiro says the CMI as a collective allows NGOs and NPOs to collaborate more effectively for children’s rights and welfare. She says it’s things like identifying child abuse cases in counselling then being able to connect with the Teddy Bear Clinic, which is on the same campus, to advance cases through the courts speedily. “There is no question that the CMI is an amazing space that allows us to work better for the children we see here,” she says.

The reality for the JPCCC currently though is that she and her team start each day carrying buckets of water to the toilets. Or they have to walk longer distances to toilets on the campus where water has not been shut off.

She says: “The other day I had to walk with a client to a toilet in another part of the building. There was a queue, so we waited. After going to the toilet we walked back to the offices. By then nearly 20 minutes of her session had been lost – this is the impact of the departments not settling their debts and paying their bills.

“It has become really hard to be in a space that is so special but now requires us to engage with government departments that don’t want to engage. Government is just not interested in us. These departments are just kicking the can between them and no one is taking responsibility,” Ribeiro says.

For Rozanne Myburgh, managing director of the Lefika La Phodiso Community Art Counselling and Training Institute, which is also based the CMI, having no reliable water and electricity has meant they are forced to cut back on group art therapy classes and scrambling to make alternative plans daily.

Myburgh says: “We all bring in containers of water from home or we use gas to cook when there’s no electricity. We try to rally and support each other but it’s not ideal because you’re just trying to respond to crises all the time. Of course, for our therapy classes we work with paints, which means children need to be able to wash their hands.

“We have had to send our larger groups of children home over the past few weeks (about 60 children daily), but this has a huge impact because we also run a nutrition programme. Every day a child misses art therapy class here they’re also losing out on a meal that day. And we are talking about some very vulnerable inner-city children.”

What the government officials should understand, she says, is that children are suffering. Myburgh adds: “Many of the children who come to Lefika and to CMI call this their home. It’s a building that holds a lot of meaning for children, many of whom know they can just walk off the street and come here. And when you lose your sense of home, you lose the place where you feel safe.” DM

Daily Maverick sent questions to representatives and communications teams of the Gauteng departments of health, education and infrastructure and development, also to Gladys Bogoshi, the CEO of CMJAH, and Simangele Tshabalala, the principal of the Johannesburg School for Autism. Not one of these government representatives responded.

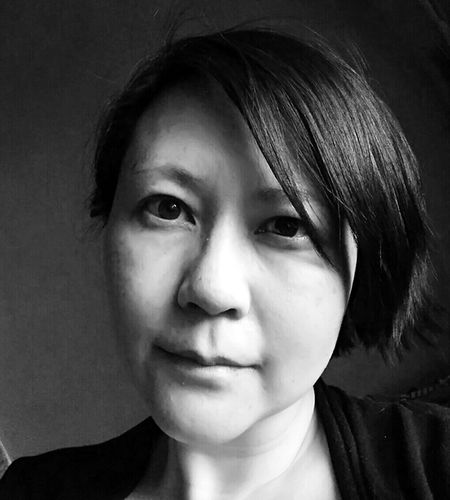

Gladys Bogoshi (CEO of the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Hospital ) gives an update at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital on February 17, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The update follows a fire outbreak at the hospital last year, which caused extensive structural damage. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sharon Seretlo)

Gladys Bogoshi (CEO of the Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Hospital ) gives an update at Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital on February 17, 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa. The update follows a fire outbreak at the hospital last year, which caused extensive structural damage. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sharon Seretlo)