PHOTOGRAPHY

2023 Sony World Photography Awards: Environment and Wildlife

The Sony World Photography Awards returns to celebrate contemporary photography and the ways the arts reflect the world around us. Here is a selection of the images from the winners of this year's national awards in the Environment and Wildlife categories.

“Battle for Survival”. For three years I have been photographing wildlife, primarily in Kenya, and documenting the Great Migration. In this time I have witnessed the impact of climate change and human activity on the ecological environment during the Covid pandemic. Over the first year of the pandemic, Masai Mara National Reserve’s wildlife became significantly more comfortable, with less disturbance from global tourists. The migration of animals across the river in 2020 was also the most spectacular in recent years. Due to the unpredictability of the event, photographing wildebeest herds crossing a river remains difficult, though, and a single great shot can take several weeks of patience and dedication. © Zhu Zhu, Canada, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Below the Surface”. A split shot of the mobula ray fever cruising below the surface. A series of photographs taken below, above and within the water during the annual mobula ray migration in Baja California. The ray fever creates intriguing dynamic patterns and textures underwater, in contrast to the individual jumps outside the water. © Martin Broen, United States, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Full Extension”. A series of photographs taken below, above and within the water during the annual mobula ray migration in Baja California. The ray fever creates intriguing dynamic patterns and textures underwater, in contrast to the individual jumps outside the water. © Martin Broen, United States, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“City Howl”. Cities Gone Wild is an exploration of three savvy animals — black bears, coyotes and raccoons — that have uniquely equipped to survive and even thrive in the human built landscape while other animals are disappearing. I tracked these animals in cities across America to reveal a more intimate view of how wildlife is adapting to increased urbanization. © Corey Arnold, United States, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Janice and Cubs”. “Cities Gone Wild” is an exploration of three savvy animals — black bears, coyotes and raccoons — that have uniquely equipped to survive and even thrive in the human built landscape while other animals are disappearing. I tracked these animals in cities across America to reveal a more intimate view of how wildlife is adapting to increased urbanization. © Corey Arnold, United States, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Blondy”. Blondy the cow. This series considers the idea that for centuries humans have used tags and rings to identify livestock, and decorated horses, meanwhile dogs have to wear a collar, which is not only practical, but increasingly like a chic piece of jewellery. In the beginning I didn’t really know if it would work well. Would it look too contrived? Maybe kind of kitschy? © Julia Christe, Germany, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Sophia”. Sophia the dog. This series considers the idea that for centuries humans have used tags and rings to identify livestock, and decorated horses, meanwhile dogs have to wear a collar, which is not only practical, but increasingly like a chic piece of jewellery. In the beginning I didn’t really know if it would work well. Would it look too contrived? Maybe kind of kitschy? © Julia Christe, Germany, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“The Forest Comes Alive at Night”. Millions of synchronously flashing fireflies light up the forests of Anamalai Tiger Reserve while the stars twinkle above. This image was created by stacking several photographs taken over a 16 minute period. Searching for stars near my hometown of Pollachi, India, I was led to the forests of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve. The further I moved away from the towns and their lights, the darker it got and the more I could see stars and fireflies. I was fascinated by the hundreds of fireflies flashing at the edge of the forest, but recalled hearing stories of trees laden with fireflies deep in the forest. So, in April 2022, I set out to a remote area of the reserve with forest officials. Flashes of green started appearing at twilight and as the place grew dark, millions of fireflies started synchronising their flashes across several trees. The flashes would start in one tree and continue across other trees like a Mexican wave. Such large congregations of fireflies are very rare, and this series captures the phenomenon of fireflies turning an entire forest into a magical carpet of yellowish-green light. The images were created by stacking several photographs. © Sriram Murali, India, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“A Valley of Fireflies”. Anamalai Tiger Reserve is a biodiversity hotspot known for its megafauna and flora, but for a few days every year it is this tiny insect that steals the show at night. This image was created by stacking several photographs taken over a 16 minute period. Searching for stars near my hometown of Pollachi, India, I was led to the forests of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve. The further I moved away from the towns and their lights, the darker it got and the more I could see stars and fireflies. I was fascinated by the hundreds of fireflies flashing at the edge of the forest, but recalled hearing stories of trees laden with fireflies deep in the forest. So, in April 2022, I set out to a remote area of the reserve with forest officials. Flashes of green started appearing at twilight and as the place grew dark, millions of fireflies started synchronising their flashes across several trees. The flashes would start in one tree and continue across other trees like a Mexican wave. Such large congregations of fireflies are very rare, and this series captures the phenomenon of fireflies turning an entire forest into a magical carpet of yellowish-green light. The images were created by stacking several photographs. © Sriram Murali, India, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

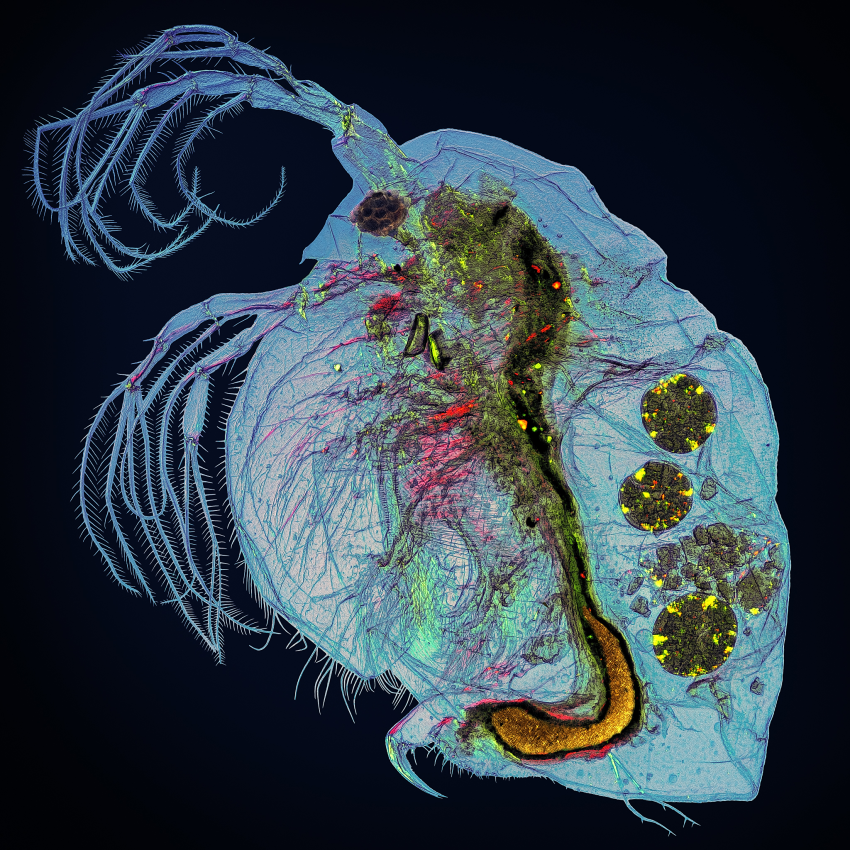

“Water Flea (4x)”. Water flea in polarised light. Small, inconspicuous, mostly grey insects, spiders and crabs reveal many colours and interesting structures under high magnification and polarised backlight. All of these high-resolution photographs were taken through a microscope using a self-made setup, and the raw images were processed, stacked and retouched. © Adalbert Mojrzisch, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Hard-Bodied Tick (20x)”. Backlit hard-bodied tick. Small, inconspicuous, mostly grey insects, spiders and crabs reveal many colours and interesting structures under high magnification and polarised backlight. All of these high-resolution photographs were taken through a microscope using a self-made setup, and the raw images were processed, stacked and retouched. © Adalbert Mojrzisch, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Arcadia Place 5”. In late 2022 I visited this overgrown plot near to where I live in Observatory, Cape Town. A few years ago, an old retirement home in my neighbourhood was demolished to make way for a larger home for the aged. However, the construction has been delayed and the plot of land left to its own devices. An array of weeds has now sprung up among the rubble, interweaving with the wild growth of the surviving flora of the original gardens. High walls hide the plot from the busy streets that surround it, but the presence of humans is evident in the scattering of wind-blown rubbish that rests amongst the foliage. This still feels like a protected space, though, and has even become home to a colony of bees. The old retirement home was called Arcadia Place, a name that suggests a peaceful pastoral setting. This seems even more appropriate now, although construction will eventually begin and this inadvertent sanctuary will come to an end. © Dillon Marsh, South Africa, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Arcadia Place 8”. In late 2022 I visited this overgrown plot near to where I live in Observatory, Cape Town. A few years ago, an old retirement home in my neighbourhood was demolished to make way for a larger home for the aged. However, the construction has been delayed and the plot of land left to its own devices. An array of weeds has now sprung up among the rubble, interweaving with the wild growth of the surviving flora of the original gardens. High walls hide the plot from the busy streets that surround it, but the presence of humans is evident in the scattering of wind-blown rubbish that rests amongst the foliage. This still feels like a protected space, though, and has even become home to a colony of bees. The old retirement home was called Arcadia Place, a name that suggests a peaceful pastoral setting. This seems even more appropriate now, although construction will eventually begin and this inadvertent sanctuary will come to an end. © Dillon Marsh, South Africa, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

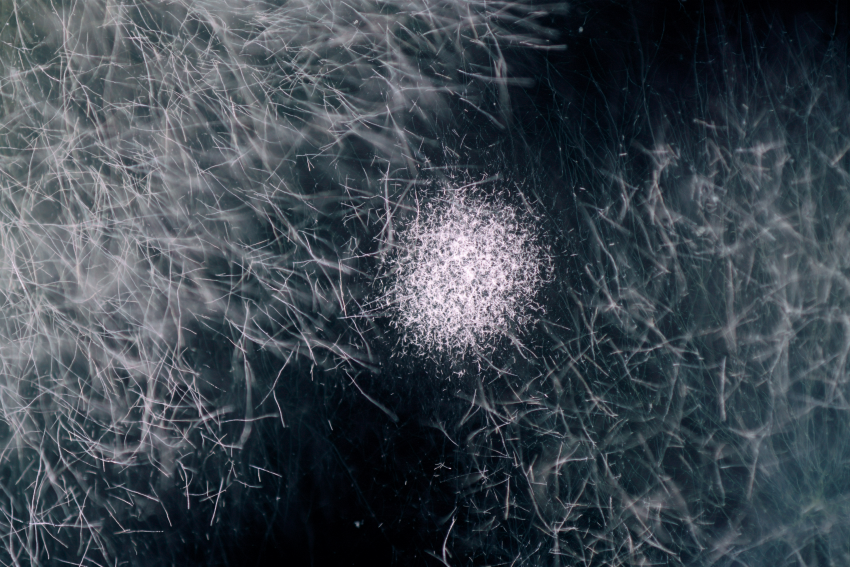

“Mould Cosmos 1”. I took this photograph to show the beauty of moulds, which are often disliked, but exist all around us. Mould is a common and widely hated feature of life. However, very few people recognise how important it is for the ecosystem, which is why I created this series. Taken over a one-year period, my goal is to reveal the unknown aspects and beauty of mould, by photographing different moulds growing in an agar medium. © Masahiro Fujita, Japan, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Mould Cosmos 4”. I took this photograph to show the beauty of moulds, which are often disliked, but exist all around us. Mould is a common and widely hated feature of life. However, very few people recognise how important it is for the ecosystem, which is why I created this series. Taken over a one-year period, my goal is to reveal the unknown aspects and beauty of mould, by photographing different moulds growing in an agar medium. © Masahiro Fujita, Japan, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Almost There”. Chillikomban trying hard to get hold of a jackfruit. This series follows a lone tusker with slender, twig-sized tusks. The locals call him ‘Chillikomban’ and his home range is mostly in the Nelliyampathy Hills in the Anamalai Ranges of the Western Ghats mountains in southern India. He spends most of his time in and around human habitations, negotiating steep hills, tea estates and misty roads. I have been following and observing this tusker for more than a decade now and have been fortunate enough to witness some of the most beautiful moments of his life. This has helped me understand more about elephants and the tolerance level of native people towards certain individuals. © Aneesh Sankarankutty, India, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Crowd Puller”. With his majestic figure and character, Chillikomban always draws a crowd. Here he stands watching a group of people playing volleyball. This series follows a lone tusker with slender, twig-sized tusks. The locals call him ‘Chillikomban’ and his home range is mostly in the Nelliyampathy Hills in the Anamalai Ranges of the Western Ghats mountains in southern India. He spends most of his time in and around human habitations, negotiating steep hills, tea estates and misty roads. I have been following and observing this tusker for more than a decade now and have been fortunate enough to witness some of the most beautiful moments of his life. This has helped me understand more about elephants and the tolerance level of native people towards certain individuals. © Aneesh Sankarankutty, India, Shortlist, Professional competition, Wildlife & Nature, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Government Apathy”. Faced with the challenge of disposing of the waste marble, Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation (RIICO) and the Kishangarh Marble Association initially decided to store it in one specific area. However, as the pile of waste grew, it took on the shape of the snowy hill, spread over more than 125 acres. During the second phase of this dumping, which was completed in 2009, the local marble association had around 200 tankers dumping the slurry non-stop. Kishangarh is situated in the Ajmer district of the Indian state of Rajasthan, 29 kilometres (18 miles) north west of Ajmer and 90 kilometres (55 miles) from Jaipur. Kishangarh’s economy depends primarily on marble trading, and the rock is used widely for its beauty in architecture and sculpture. However, marble slurry is a big problem. The by-product of processing and polishing marble, the slurry takes up a lot of space and is an environmental hazard, especially after it has dried. The poor air quality, caused by the dust, weakens people’s immune systems, while the minute dust particles lead to respiratory diseases, such as bronchitis, among the local population. In other countries this might prompt mine owners to close their sites in anticipation of legal action, but here the operators are taking a different, more enterprising course of action, and people from across India and beyond are actually travelling to visit the waste sites. © Haider Khan, India, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“The Last Journey”. The fine marble dust causes respiratory ailments in nearby residential areas, as well as affecting the flora and fauna. Continuous exposure to marble dust can cause severe respiratory disorders, such as bronchitis, asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), although dermal and eye irritation are by far the most common problems. The dust has also become a safety hazard on the highways along which it is dumped, as it creates visibility issues when it is dry and airborne, and makes the roads slippery when it is wet. Kishangarh is situated in the Ajmer district of the Indian state of Rajasthan, 29 kilometres (18 miles) north west of Ajmer and 90 kilometres (55 miles) from Jaipur. Kishangarh’s economy depends primarily on marble trading, and the rock is used widely for its beauty in architecture and sculpture. However, marble slurry is a big problem. The by-product of processing and polishing marble, the slurry takes up a lot of space and is an environmental hazard, especially after it has dried. The poor air quality, caused by the dust, weakens people’s immune systems, while the minute dust particles lead to respiratory diseases, such as bronchitis, among the local population. In other countries this might prompt mine owners to close their sites in anticipation of legal action, but here the operators are taking a different, more enterprising course of action, and people from across India and beyond are actually travelling to visit the waste sites. © Haider Khan, India, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

The water level of Lake Mead has decreased drastically over the last few years. Arizona/Nevada, November 2021. The Colorado River once stretched for more than 2,000km (1,200 miles) across the western United States, from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California. However, extensive agriculture, dams, huge canal systems and the diversion of water to growing cities in the desert have changed the river, which has been drying up and no longer reaches the delta. Today, more than 44 million people depend on the water of the Colorado, but less snowfall in the mountains has intensified the struggle for water rights, with farmers having to file for bankruptcy and hedge funds buying farms to get their water rights. © Jonas Kakó, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

Antonia Torres Gonzáles on the banks of the Colorado near El Mayor, Mexico. Antonia fears that with the river and its fish both disappearing, the traditions of the Cucupá will fade, as younger people of the tribe move away to find work. Antonia tries to preserve their culture by teaching the young generations beadwork and rituals. The Colorado River once stretched for more than 2,000km (1,200 miles) across the western United States, from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California. However, extensive agriculture, dams, huge canal systems and the diversion of water to growing cities in the desert have changed the river, which has been drying up and no longer reaches the delta. Today, more than 44 million people depend on the water of the Colorado, but less snowfall in the mountains has intensified the struggle for water rights, with farmers having to file for bankruptcy and hedge funds buying farms to get their water rights. © Jonas Kakó, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Željezara 5”. Bosnia and Herzegovina has the fifth highest incidence of deaths from air pollution in the world, while rates of lung disease are also among the highest. Zenica currently records one of the highest levels of air pollution in the country, causing many people to suffer from respiratory problems, as well as cancer. The town’s residents have opposed the factory’s rudimentary maintenance and are demanding an improvement in environmental protection. Under Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslavia, the city of Zenica developed rapidly as a centre for steel and coal, becoming one of the country’s most important exporters. The steel plant expanded enormously and became one of the largest in Europe; by 1991 Zenica had more than 150,000 inhabitants, with its many grey high-rise buildings giving it the reputation of a rough, working-class town. However, following its privatisation and the economic decline of Bosnia after the Yugoslav war, the number of employees decreased to barely 2,000, and production never returned to its pre-war level. Today, Zenica has one of the highest levels of air pollution in the country and many people suffer from respiratory problems and cancer. At the same time, though, the factory remains the city’s largest employer and an important pillar in Bosnia’s economic system. It is both a curse and a blessing. The fate of the factory and that of the city are inextricably linked: the decline of one means the decline of the other. © Lasse Branding, Germany, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Željezara 9”. An estimated 90 percent of Zenica’s population is Muslim. During the fasting month of Ramadan, many of the city’s residents hike together through the surrounding mountains and break their fast together after sunset. The initiator of the hikes, Afan Abazovic, calls it ‘Iftar Hiking’. Under Josip Broz Tito’s Yugoslavia, the city of Zenica developed rapidly as a centre for steel and coal, becoming one of the country’s most important exporters. The steel plant expanded enormously and became one of the largest in Europe; by 1991 Zenica had more than 150,000 inhabitants, with its many grey high-rise buildings giving it the reputation of a rough, working-class town. However, following its privatisation and the economic decline of Bosnia after the Yugoslav war, the number of employees decreased to barely 2,000, and production never returned to its pre-war level. Today, Zenica has one of the highest levels of air pollution in the country and many people suffer from respiratory problems and cancer. At the same time, though, the factory remains the city’s largest employer and an important pillar in Bosnia’s economic system. It is both a curse and a blessing. The fate of the factory and that of the city are inextricably linked: the decline of one means the decline of the other. © Lasse Branding, Germany, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

A group of Wayuu children in Polumacho with Emilio, the leader of the village, in November 2021. Emilio told us: ‘At the moment we don’t have enough water; what water we do have we can’t use for drinking. The times of drought have always been difficult. That happens in the months of January, February, from then for about three or four months. If the year goes by and it doesn’t rain, it is very difficult.’ Miruku focuses on the Wayuus, an indigenous population from La Guajira, Colombia’s coastal desert. Commissioned by 1854/British Journal of Photography and WaterAid, the project examines how a combination of climate change issues and human negligence have led its various members to experience a stifling water shortage. In the region, the problem is cyclical and polymorphous. While some communities can achieve certain stability during rainy seasons, temperatures are bound to rise, drying up the land again. Global warming only aggravates this, causing droughts and famine, and spoiling the facilities and installations that help source clean water. We framed the story from a female perspective to get a better understanding of how gender inequality and climate vulnerability interrelate. We sought to highlight the strength and resourcefulness of the Wayuu women, as we found it inspiring that, even under such conditions, they have established themselves as community leaders, teachers and climate activists. Through our diptychs we wanted to convey a visual balance between a raw and a lyrical documentation, and achieve a nuanced portrayal of a multihued situation. © Marisol Mendez (Bolivia) & Federico Kaplan (Argentina), Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

Left: Nina (7), a girl from Polumacho, displays the stickers she got for completing her colouring activities.

Right: A dead bird at the door of a house in Pesuapa. For the Wayuu communities, women are authorities, artisans, carers, providers – and ultimately – water defenders. Many Wayuu women travel for hours to source water from wells or natural aquifers called jagüeyes. Miruku focuses on the Wayuus, an indigenous population from La Guajira, Colombia’s coastal desert. Commissioned by 1854/British Journal of Photography and WaterAid, the project examines how a combination of climate change issues and human negligence have led its various members to experience a stifling water shortage. In the region, the problem is cyclical and polymorphous. While some communities can achieve certain stability during rainy seasons, temperatures are bound to rise, drying up the land again. Global warming only aggravates this, causing droughts and famine, and spoiling the facilities and installations that help source clean water. We framed the story from a female perspective to get a better understanding of how gender inequality and climate vulnerability interrelate. We sought to highlight the strength and resourcefulness of the Wayuu women, as we found it inspiring that, even under such conditions, they have established themselves as community leaders, teachers and climate activists. Through our diptychs we wanted to convey a visual balance between a raw and a lyrical documentation, and achieve a nuanced portrayal of a multihued situation. © Marisol Mendez (Bolivia) & Federico Kaplan (Argentina), Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

A Kuchi-Baranghi herder leads his flock from the Shiwa pastures in the north of Badakhshan, towards the plains in the province of Kunduz. Families used to spend the entire summer here, but now they begin to depart at the end of July and the beginning of August due to the exhaustion of the pastures. In recent years, drought has made it much harder and less predictable for the nomadic Kuchi herders of Afghanistan to make use of the available pastures. This has inflamed historic tensions with another nomadic group, the Hazara, and in some areas the Kuchi are now allowed only to bring their herds, but not their tents. Such are the pressures that families have been forced to sell their camels and their flocks have reduced significantly in number, while groups that used to spend entire summers in the mountains are now leaving earlier than usual due to the exhaustion of the pastures. Because of this, many herders have to buy forage to feed their flocks, as well as water for their families – those who can afford it buy it from water tankers and create small ponds in which to store it. © Bruno Zanzottera, Italy, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

Shirin Aigha and Bismillah, two Kuchi-Farjayan boys, fetch water for their family’s flocks in the northern province of Kunduz. Due to droughts they have had to buy water from tankers and store it in this small homemade pond they have built. In recent years, drought has made it much harder and less predictable for the nomadic Kuchi herders of Afghanistan to make use of the available pastures. This has inflamed historic tensions with another nomadic group, the Hazara, and in some areas the Kuchi are now allowed only to bring their herds, but not their tents. Such are the pressures that families have been forced to sell their camels and their flocks have reduced significantly in number, while groups that used to spend entire summers in the mountains are now leaving earlier than usual due to the exhaustion of the pastures. Because of this, many herders have to buy forage to feed their flocks, as well as water for their families – those who can afford it buy it from water tankers and create small ponds in which to store it. © Bruno Zanzottera, Italy, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

Located in the industrial outskirts of Copenhagen, Denmark, Amager Bakke is a combined heat and power waste-to-energy plant. It is not only the world’s cleanest waste-to-energy facility, but also home to a recreational area with its own ski slope, the world’s tallest climbing wall and hiking trails up the building. The plant serves 680,000 people and takes waste from up to 300 lorries every day. Climate change is the greatest threat the world is currently facing. The challenge that lies ahead requires us to change our perspective and redesign humanity, so it is no longer separate from its ecosystem, but one with the planet it inhabits. The EU has set targets to cut emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030, and to reduce them to net-zero by 2050. Renewable energies, new technologies for food production and the circular economy are key solutions for achieving these Green Deal goals, and many revolutionary seeds have already been planted across Europe to make the future sustainable for the next generations. The net-zero transition has already started and is set to be the next industrial revolution: these innovative technologies lead the way towards climate neutrality, inspiring a virtuous model that will generate a new and sustainable cycle of life. © Simone Tramonte, Italy, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

A view of Middelgrunden offshore wind farm from Amager Strand, a very popular beach in Copenhagen. Middelgrunden wind farm is producing electricity for more than 40,000 households in Copenhagen. Danish citizens have played an important part in turning the country into a strong wind-powered nation; today, 14.4 percent of Denmark’s electricity consumption is provided by wind. Climate change is the greatest threat the world is currently facing. The challenge that lies ahead requires us to change our perspective and redesign humanity, so it is no longer separate from its ecosystem, but one with the planet it inhabits. The EU has set targets to cut emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030, and to reduce them to net-zero by 2050. Renewable energies, new technologies for food production and the circular economy are key solutions for achieving these Green Deal goals, and many revolutionary seeds have already been planted across Europe to make the future sustainable for the next generations. The net-zero transition has already started and is set to be the next industrial revolution: these innovative technologies lead the way towards climate neutrality, inspiring a virtuous model that will generate a new and sustainable cycle of life. © Simone Tramonte, Italy, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“The Lost Lake 4”. Darabala Abdel Hadi (61) poses for a portrait on the shore at Lake Qarun. Darabala worked with his father for 20 years as a fisherman on the lake, but when fish stocks declined sharply due to severe pollution, he was forced to abandon Ezbat Soliman and move to the village of Abu Simbel in the south of Egypt. Lake Qarun, located in the Fayoum in south west Egypt, is one of the oldest lakes in the world, containing fossils that are millions of years old. During the Pharaonic era, flooding meant that this low-lying lake was supplied with freshwater from the Nile, but since the start of the 20th Century it has grown increasingly saline. Various fish species have already disappeared due to increased pollution and changes to the climate, and the health of Lake Qarun and the wildlife within it are now seriously endangered by its rising saline level, which is higher than that of seawater. To compound this, a parasitic infection has spread throughout the lake, which has negatively impacted fish production and quality, thereby harming the fishing community in Fayoum: the number of fishing boats operating in the lake has decreased from 605 to just 10 boats. This project attempts to explore the lives of the fishermen residing in the village of Ezbat Soliman, near Lake Qarun, and how the lake’s pollution affects them. © Fatma Fahmy, Egypt, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“The Lost Lake 8”. Two children pause for a photograph at Lake Qarun. In summer, many people come from Fayoum, Beni Suef and Giza to bathe in the lake, but most are unaware of the dangers caused by untreated sewage, agricultural wastewater and industrial waste. Lake Qarun, located in the Fayoum in south west Egypt, is one of the oldest lakes in the world, containing fossils that are millions of years old. During the Pharaonic era, flooding meant that this low-lying lake was supplied with freshwater from the Nile, but since the start of the 20th Century it has grown increasingly saline. Various fish species have already disappeared due to increased pollution and changes to the climate, and the health of Lake Qarun and the wildlife within it are now seriously endangered by its rising saline level, which is higher than that of seawater. To compound this, a parasitic infection has spread throughout the lake, which has negatively impacted fish production and quality, thereby harming the fishing community in Fayoum: the number of fishing boats operating in the lake has decreased from 605 to just 10 boats. This project attempts to explore the lives of the fishermen residing in the village of Ezbat Soliman, near Lake Qarun, and how the lake’s pollution affects them. © Fatma Fahmy, Egypt, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Guardians of the Glaciers 3”. ‘The cold waves are much harder to bear now, with temperatures getting lower because of climate change. There is almost no rain, there is no water, the animals die, it is worrying in the heights of the Andes’, says one of the community elders, posing for a portrait in his cabin in Cusco, Peru. Ice constitutes the second largest source of freshwater on the planet and 70 percent of the world’s tropical glaciers are found in Peru. Located in Cusco, the Quelccaya Ice Cap is the largest tropical glacier in the world, covering an area equivalent to more than 9,000 soccer fields. However, due to accelerated melting it is receding by 60 metres (195 feet) a year and some studies have determined that it will disappear in the next 30 years if global greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced. The inhabitants of the Quechua community, who live on the slopes and close to the glacier, are being affected directly by the retreating ice and dedicate their lives to making the population aware of the problem of melting ice as an effect of climate change. They seek to protect their snow-capped mountains through ancestral knowledge and rituals of the Andean worldview, which over time are also disappearing. The thaw not only threatens the continuity of life in Andean communities, but also puts certain species at risk of extinction, as these areas are inhabited by a range of aquatic and terrestrial species. © Angela Ponce, Peru, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

“Guardians of the Glaciers 5”. Teresa observes the snowy ice cap, while remembering her father. ‘My dad always made offerings to the snowy mountain. He told me that it would be the end of the world when the snow melted’. For many local people the mountains are sacred and considered gods. Ice constitutes the second largest source of freshwater on the planet and 70 percent of the world’s tropical glaciers are found in Peru. Located in Cusco, the Quelccaya Ice Cap is the largest tropical glacier in the world, covering an area equivalent to more than 9,000 soccer fields. However, due to accelerated melting it is receding by 60 metres (195 feet) a year and some studies have determined that it will disappear in the next 30 years if global greenhouse gas emissions are not reduced. The inhabitants of the Quechua community, who live on the slopes and close to the glacier, are being affected directly by the retreating ice and dedicate their lives to making the population aware of the problem of melting ice as an effect of climate change. They seek to protect their snow-capped mountains through ancestral knowledge and rituals of the Andean worldview, which over time are also disappearing. The thaw not only threatens the continuity of life in Andean communities, but also puts certain species at risk of extinction, as these areas are inhabited by a range of aquatic and terrestrial species. © Angela Ponce, Peru, Shortlist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023

In packing factories like this one in Aztecavo, work is done in shifts, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Michoacan is the only region in the world where avocados can be harvested all year. The popularity of avocado has exploded in recent decades, with the burden of the rising demand falling mainly on the Mexican state of Michoacan. High international demand has led to more extensive and numerous plantations, with forests now being cleared illegally to plant more avocados. It is easy to see why, as more than 300,000 jobs directly or indirectly depend on the production and trade of avocados in the region, which generates an annual revenue of US$2.5 billion. In 2021, Michoacán produced some 1.8 million tons of the green fruit and drug cartels have now become drawn to the revenue potential from the avocado trade. As violence escalates, the government has had to send in the military to maintain order, and in mid-2022, exports to the United States – the largest consumer of the fruit – had to be halted temporarily. © Axel Javier Sulzbacher, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, 2023 Sony World Photography Awards

The popularity of avocado has exploded in recent decades, with the burden of the rising demand falling mainly on the Mexican state of Michoacan. High international demand has led to more extensive and numerous plantations, with forests now being cleared illegally to plant more avocados. It is easy to see why, as more than 300,000 jobs directly or indirectly depend on the production and trade of avocados in the region, which generates an annual revenue of US$2.5 billion. In 2021, Michoacán produced some 1.8 million tons of the green fruit and drug cartels have now become drawn to the revenue potential from the avocado trade. As violence escalates, the government has had to send in the military to maintain order, and in mid-2022, exports to the United States – the largest consumer of the fruit – had to be halted temporarily. © Axel Javier Sulzbacher, Germany, Finalist, Professional competition, Environment, Sony World Photography Awards 2023 DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.