YOLISWA DWANE MEMORIAL LECTURE

‘Every generation has its struggle’ – Activism and the law in the fight for social justice

On 24 February 2023, Jason Brickhill delivered Equal Education’s inaugural Yoliswa Dwane Memorial Lecture at the University of Cape Town. In 2008, Yoliswa Dwane was a co-founder of Equal Education, the social movement dedicated to fighting to ensure the constitutional right to basic education. Between 2012 and 2018, she was elected as its national chairperson. Sadly, on 21 October 2022, at the young age of 40, Yoliswa succumbed to liver cancer. Below, we publish in full this important lecture which reflects on social movements’ use of law and the contribution of Dwane.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Yoliswa Dwane, co-founder of Equal Education, dies aged 40

Good afternoon, molweni, sanibonani, masikati, goeie middag,

I do not take lightly the honour of being asked to give this lecture, the inaugural lecture to remember Yoliswa Dwane. I recognise that, coming so soon after Yoliswa’s passing, the pain of her loss is still close and heavy for many people. We come together to honour her contribution – to celebrate it, and to reflect on what it can teach us.

I realise, too, that I am speaking on the occasion of Equal Education’s (EE) 15th anniversary – a movement into which so many of you present and, so many others, have poured your life’s passions and hopes for a just and equal world. I speak as an outsider to the movement – yes, a long-time ally – but an outsider all the same.

In preparing this lecture, I have drawn on my experience litigating education cases with and alongside EE, especially the Norms and Standards case, as well as my own doctoral research at the University of Oxford from 2016-2021.

I am going to speak to the relationship between activism, law and social justice. I will begin with the tale of the Norms and Standards campaign and EE’s decision to turn to the courts. I will distill certain distinctive features of EE’s approach to activism and law. I will ask what impact this struggle has had, drawing on my doctoral research findings. Finally, I will ask what lessons and implications all this has for today’s broader struggle for social justice.

I worked with Yoliswa in the early stages of EE’s life as a movement. We collaborated on its first major case and flagship campaign for Norms and Standards for School Infrastructure. Of course, this was a massive team effort: within the Legal Resources Centre (where I was then working), and among the school communities that gathered evidence of the infrastructure crisis.

Geoff Budlender, also an alumnus of UCT and the “mkhulu” of public interest litigation in South Africa, led the legal team; and LRC attorney Cameron McConnachie, himself a former Eastern Cape teacher, was the fulcrum of the case, coordinating massive efforts to gather evidence from schools across the country. LRC’s regional director for Makhanda, Sarah Sephton; Rufus Poswa, a paralegal; and several other LRC staff played vital roles.

A powerful EE team – from national leadership to many Equalisers, too many to mention by name without leaving people out – drove the strategy and advocacy, and organised learners, teachers and parents across the country to tell their stories on affidavit, painting a picture of the daily experience of learning and teaching in broken, ill-equipped and often dangerous schools.

Yoliswa played a leading role, and she ultimately deposed to the main founding affidavit on behalf of EE. I remember her, during that Norms and Standards time, as being direct, decisive and straight-forward. She was not one for long emails when a short one would do. She was all about the movement and about its objectives, not about getting attention or acclaim.

I have since learnt that Yoliswa and I had much more in common. We were both born in the same year, 1981, to parents who served in uMkhonto we Sizwe during the liberation struggle. We both studied law right here, at UCT. Despite all this, Yoliswa and I reached UCT following different paths and with backgrounds shaped by apartheid and the persistence of patriarchy, white privilege and black disadvantage.

Growing up in exile in Zimbabwe, I had the benefit of an excellent, affordable government school education – one of the great triumphs of early post-independence Zimbabwe being public education, though it has faded considerably in recent years. Yoliswa lived and grew up in Dimbaza Township near King William’s Town in the Eastern Cape, where public schooling was and is far from a triumph, experiencing first-hand the inequality in South African schooling. She was one of 12 learners to pass matric in her year. Later, she graduated from UCT as one of three black South Africans in the class of 2007, despite those hurdles.

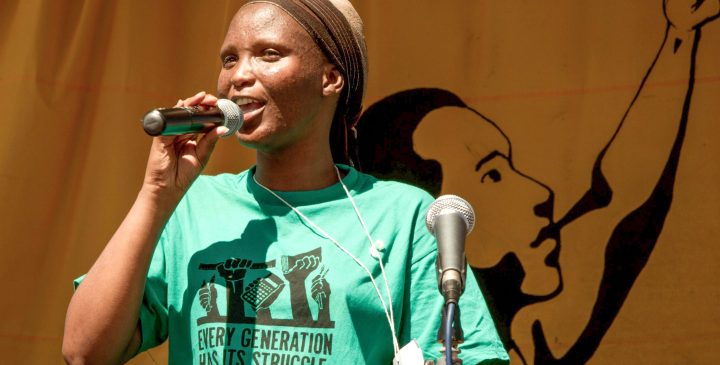

Our generation is still faced with an unequal education system, with inferior standards of education for many poor and working class children. (Photo: Equal Education)

The Norms and Standards struggle

EE was formed in 2008. Yoliswa was one of its four founders. Its largest campaign to date is the Norms and Standards campaign. What was this all about?

The school system is governed by the South African Schools Act. It is a transformative law in its design, aiming to build a single, inclusive and progressive education system for all. Section 5A(1)(a) of the Schools Act provides that the Minister “may, after consultation with the Minister of Finance and the Council of Education Ministers, by regulation prescribe minimum uniform norms and standards for school infrastructure”.

This provision gave the Minister the legal power to make law in the form of binding regulations to inform what all schools in the country should look like, and to prescribe a timeframe and require government plans for how this should be achieved. The Minister had never done this, only publishing non-binding guidelines.

Though section 5A is couched in permissive language, using the word “may”, EE argued that the Minister was required to make Norms and Standards given the government’s constitutional obligation to provide basic education.

The effect of the Norms and Standards would be to set a national minimum standard for public school infrastructure in regulations with the status of binding law, not mere policy. Although the Act gave the national Minister the power to make Norms and Standards, the obligations to implement them and provide the infrastructure would fall primarily on provincial governments.

Before even considering litigation, EE engaged in various forms of advocacy and protest, including extensive letters, petitions, marches and other forms of protest action, securing promises from the Minister – on which she later reneged. EE eventually turned to litigation as a last resort, represented by the LRC.

Building the evidence and preparing the founding papers for the Norms and Standards litigation was a remarkable effort by EE and the LRC. Teams visited schools across the country to gather evidence of the conditions, and for learners at those schools to explain, in their own words, how those conditions affected their learning and their lives.

I would like to read you a few extracts from Yoliswa’s 82-page founding affidavit, which really captures EE’s approach. She explained the background to the case:

[6] “Since its inception, EE has been concerned with learning conditions in poor and working class schools and communities. Our very first campaign was aimed at ensuring that over 500 broken windows at a school in Khayelitsha were fixed so as to improve the school’s physical conditions and to ensure that teachers and learners could better focus in the classroom.

[7] “We have engaged provincial and national departments through meetings, letters, petitions, pickets, marches, night vigils, and a 24-hour sleep-in at the gates of Parliament. Our marches have taken place in Cape Town, Johannesburg, Tshwane, Polokwane and Bhisho. Over 100,000 people in South Africa have signed our petitions and over 40,000 have marched in our marches. All of our activities have been peaceful.”

The rest of the founding affidavit painted a stark picture of the conditions at the two applicant schools, Mwezeni Senior Primary School and Mkanzini Junior Secondary School, as well as a further 24 schools from which a learner, teacher, parent or School Governing Body member provided an affidavit.

It was a devastating, unanswerable account of the conditions in which learning and teaching were taking place – of mud school structures and missing roofs, of unstable walls and classrooms without windows, of schools without water, electricity, toilets, libraries, laboratories or outer fences.

An unanswerable account, yes – but the government nevertheless opposed, citing resource constraints, the scale of the challenge and the need to be left to fix schools in their own time.

Let me pause to say something about EE as a client. As someone who has acted for many movements, communities and organisations, government in all spheres, for subsistence fishing communities and listed corporations, for a Kingship and a foreign head of state, let me say that EE stands out among all of them … as an exceptionally difficult client – difficult in all the best ways. The EE people on the cases would engage with every detail, weigh up every tactic and strategy, would debate with their lawyers. This made the work charged and stimulating, produced carefully crafted court papers and a coherent messaging inside and outside the courtroom.

Let me return to the plot. All the court papers and heads of argument were in. We readied ourselves for the hearing to take place on 20 November 2012. While the legal team geared up to argue, EE was also making preparations – to hold a #FixOurSchools overnight camp of 150 members outside the court in Bhisho.

On 19 November 2012, the eve of the hearing, with EE members setting up to camp, the Minister capitulated and the parties concluded a settlement agreement. The Minister agreed to everything that we had asked for – to provide the two applicant schools with sufficient infrastructure and to promulgate binding Norms and Standards, for all schools.

We celebrated the victory. This was constitutional alchemy in action. We had turned “may” into “must” and the Minister would now have to make binding regulations to set minimum infrastructure standards for every public school in the country. Geoff Budlender wrote on 20 November 2012 to Yoliswa and the EE team, saying:

“It has literally been a pleasure and a privilege to be part of this team. It is the sort of work, and the sort of experience, that makes it worthwhile being a lawyer. Thank you.”

In the meantime, however, our celebrations were premature. This was far from the end of the Norms and Standards saga.

The Minister failed to publish the regulations by the deadline of May 2013. EE had to launch a further round of litigation to compel her to do so.

There was an interesting episode during this stage that highlights the tensions inherent in movement lawyering. The Minister asked for a further extension to publish the Norms. EE took the matter to a vote, and the membership said “no” to the extension. But EE’s leaders and legal team decided that it was necessary to give one more extension, that the court would give one anyway and that EE would look bad if we refused.

This led to tensions within EE, with members feeling that leadership had acted undemocratically. Yoliswa was key to mediating these tensions. She uniquely understood the tensions because of her training as a lawyer and her connection with equalisers who, like her, struggled through deficient school education. This particular episode is now used as a teaching aid at Columbia University to spark debate about movements and the law.

On 18 June 2013, days after new papers were filed to compel the Minister to publish the draft Norms, there was an unpleasant development. The DBE’s official Twitter handle tweeted that “to suddenly see a group of white adults organising black African children with half-truths can only be opportunistic & patronising”. Despite widespread condemnation, the DBE did not delete or retract the statement.

The tweet is still there to this day, on the official handle of the DBE, one of the most shameful public statements to have come from the democratic government. You can go and read the tweet, and read the responses from EE, its members and others who were justifiably outraged.

A few weeks later, though, the Minister eventually released a draft set of regulations for public comment. EE and EELC [Equal Education Law Centre] sprang into action and organised public hearings and received extensive comments from communities and organisations nationwide. During this period, the EELC had now been established as EE’s key partner in movement lawyering, although both continued to work with the LRC, SECTION27 and Centre for Child Law.

EE and the EELC workshopped the draft regulations and comments in communities and through that process many learners, parents, teachers and community members across the country engaged with the proposed regulations and put their comments into the public participation process. The Minister amended the initial draft substantially in response to comments.

On 29 November 2013, the Minister finally promulgated Norms and Standards. We now had a binding law.

However, EE was concerned that the Norms still fell short of constitutional standards, and it brought a constitutional challenge, now represented by the EELC. Lisa Draga at the EELC played the central coordinating role in relation to the comments process and now this constitutional challenge.

The challenge was upheld in the Bhisho High Court on 19 July 2018. The challenge removed an escape valve that the Minister had inserted in the Norms to justify non-compliance on the basis of lack of resources, required government to make public the plans required by the Norms and required the eradication of mud schools and dealing with schools with no sanitation, water or electricity to be prioritised.

On 29 October 2018, the Constitutional Court refused the Minister leave to appeal on the basis that there were no prospects of success, making the High Court judgment final and bringing an end to the litigation.

The now late Yoliswa Dwane speaks to activists in 2010 at an Equal Education meeting. (Photo: Gillian Benjamin, supplied by GroundUp)

Distinctive features of EE’s struggle

EE has a distinct approach to struggle, combining activism and law. In thinking about what makes EE’s approach remarkable, I identify five particular features.

First, and most distinctively, EE has prioritised building the movement. At the 2015 EE 2nd National Congress, at which she was elected chairperson, Yoliswa said:

“Comrades, we are in the 8th year of our struggle. We know what our modus operandi has been, that at the core of this movement it has been young people driving the successes of Equal Education.”

Building the movement is not just about crude numbers for EE but also about institutions, structures and, crucially, about political education. EE has rapidly built up its membership structures and recruited staff with expertise that spans education policy, research, communications and more. A distinctive feature of all of these structures, even as EE expanded in numbers and geographical reach, was, as Yoliswa pointed out, the role of young people.

Yoliswa herself led a weekly youth reading group with people like Yana van Leeve and other emerging leaders, initially under the tutelage of Rob Petersen and then independently. The group would gather in Khayelitsha every Wednesday evening and critically engage with that week’s reading on themes of gender, race, class and power, debating what it meant for contemporary South Africa.

Yoliswa understood that organising and evidence-gathering must be accompanied by analysis of the power relations that create the conditions. For her, EE was about “building an organisation that contributes to the improvement of the condition of the working class”.

Secondly, EE has articulated a positive vision for the society it wants to build. Although at times it has used disruptive tactics, it is not an anarchist movement that seeks only to tear down, destroy, remove.

In fact, most of its aims relate specifically to building – to improving infrastructure, teaching and learning in our schools. This is exemplified by EE’s campaign video, “Build the Future”, which I still use each year as a teaching aid in a master’s course on socio-economic rights that I teach at the University of Oxford.

There are so many examples of EE’s positive vision. To take one, in a 2011 interview, Yoliswa talked about EE’s library campaign:

“We advocate for a national policy on school libraries that will provide for a library in each and every school in South Africa. We know that this is a dream and a target, but it is affordable and it can be done.”

She went on to lay out the costing – about R7.9bn – to build libraries across the country for the 19,000 schools that did not have libraries. She explained that, “it is possible, it is affordable … If there is a commitment, it can be done.”

Yoliswa’s comments about the library campaign typify the approach of EE. It has allowed itself to imagine – but its imagination is informed by extensive research and the experience of members, by engaging with policy and the law. It builds dreams that, as Yoliswa says, are possible and affordable if the commitment is there. So EE’s approach is a fundamentally hopeful one, about building an ambitious but practical, positive vision of the future.

Relatedly, the third key feature of EE’s approach is that it relies on developing technical expertise and an evidence base. This is important, valuable and still too rare in South African public discourse.

Operation Dudula members protest outside the Department of Education offices in Parow while hundreds of parents queued to register their children on 17 January 2023 in Cape Town, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Brenton Geach)

Other reactionary movements and groupings, by contrast, have been overtly anti-intellectual and anti-evidence. Take Operation Dudula, for example. It builds its following on the basis not of evidence, but of outright lies about the number of migrants living in South Africa, lies about migrants’ rates of committing crime and – the biggest lie of all – that migrants deplete scarce resources (in education, health and employment).

This when all the credible evidence shows that there are less than four million migrants in South Africa (not the 15 million that Dudula claims); that migrants tend to be law-abiding and are more often victims of crime than perpetrators; and that South Africa’s problems in education, health and employment are primarily the result of wicked maldistribution of these resources and poor service delivery – not being overrun by migrants.

In sharp contrast, EE conducts its own research and also builds knowledge of policy, pedagogy and law within the movement, to enable it to bring a meaningful contribution to national discourse. Equal Education Law Centre also produces excellent Education Monitoring Briefs – in fact, the latest one came out today.

This evidence-based approach to activism and the law is profoundly important. There has not been enough of it in South Africa, especially in our universities. That is one of the reasons why I was so excited that this event is being co-hosted by UCT’s Centre for Law and Society, and that the former head of Equal Education Law Centre, Nurina Ally, is taking up the leadership of the Centre.

We urgently need to prioritise inter-disciplinary and cross-sectoral work on the relationship between law and activism in South Africa, research that builds our empirical knowledge of the effects of the law and litigation. Socio-legal research in South Africa so far has tended to be predominantly theoretical, and there are real limitations to having debates about impact and effectiveness without actually investigating the facts on the ground. EE sets a good example in this regard.

Fourthly, EE’s approach rests on solidarity – solidarity within the movement and beyond it.

In contrast is a movement like AfriForum. Good at building numbers, but narrow, sectarian, inward-looking. Not so, EE.

There are several crucial features of EE’s solidarity. Recognising that no major change was ever achieved by individuals acting alone, EE has over its 15 years built up its membership across the country. Fifteen years on, EE also now has alumni throughout South African society, broadening its reach.

With this solidarity has come a particular approach to decision-making and leadership. EE operates democratically, with the membership electing leadership and taking key decisions. This is not always easy and inevitably there will be disagreements on approach, but the membership and leadership have stood up to such challenges. Again, unlike the political parties, EE’s leadership is not about a single “big man”, but shared responsibility.

EE has also had to hold leaders and members accountable for problematic conduct, and – it seems to me – has striven to do so in a principled way, even if it is not always easy.

Most profoundly, EE’s struggle – by its members, staff and allies – is not just about those affected by the struggle today. It is largely future-looking. EE’s then General Secretary, Brad Brockman, explained to me in an interview:

“Equalisers would say things like, ‘We are not doing this for us. We are doing it for our brothers and sisters who are in primary school’ or ‘we are doing this for all other students that still need to go to school’.”

The solidarity characteristic of EE’s struggle also extends beyond EE. Alongside EE’s fight for Norms and Standards, other organisations and movements also tackled other areas of basic education. These included the EELC, Legal Resources Centre, SECTION27, Centre for Child Law and others.

I first came to work with EE while at the LRC and representing the movement. I represented EE again in the Rivonia Primary School case, which was all about the massive disparity in class sizes and government attempts to remedy this, resisted by richer schools. But at this time there were many other basic education cases and campaigns underway and different organisations would take the lead, with others playing supporting roles by intervening as a friend of the court or by supporting advocacy efforts.

We would meet regularly across these organisations, sharing plans and debating strategy. EE was a powerful partner in these collaborations and ensured that learners’ experiences and views were always in the room. Beyond the education space, EE has fostered close relationships with sister movements such as the Treatment Action Campaign, Social Justice Coalition and, later, #UniteBehind.

Unlike the political parties, which are all about attacking anyone wearing a different coloured T-shirt – EE has also worked with allies in communities, civil society, academia and even in government. Under Yoliswa’s leadership, EE was regularly present in Parliament, sitting in portfolio committees, building relationships with MPs to put the issues of Equalisers on the agenda.

Finally, EE is internationalist in its solidarity. In 2011, it produced a video on the Norms and Standards campaign, at a time when members had been sleeping outside Parliament and had been threatened with arrest. EE produced the video in Spanish, with a message of support for students in Chile. Over the last decade, Chile has been engaged in its own existential constitutional struggle, which is very much unfinished. EE saw itself as being in conversation and in solidarity with students in Chile, united in struggle despite differences of language, history and geography. EE has also supported the struggle for peace and freedom for the Palestinian people. Its internationalist solidarity is exemplary.

Fifth, and at the heart of my lecture today, EE combines activism and law, using litigation and law reform advocacy as key strategies, but in its own distinctive way. EE has harnessed the power of the Constitution, recognising its potential as a site and tool of struggle.

In doing so, EE has not chosen the path of some who reject the Constitution. Along that path of so-called constitutional abolitionism, there lies no hope for the future; only despair about the present. EE has chosen the path of constitutional hope. It is not a naïve or passive hope, but the hope that rests in taking the future into one’s own hands.

Indeed, EE’s use of the Constitution stands as a powerful empirical, evidence-based and factual answer to those who critique the Constitution’s competence, most of whom do so without making any serious effort to investigate the effect of legal activism or even to read the case law in the books.

EE’s particular approach to combining activism and the law is a powerful contemporary illustration of movement lawyering. When we were building the Norms and Standards case, alongside EE’s political actions, Geoff Budlender said that Norms and Standards reminded him very much of the TAC case, in which he had been TAC’s attorney. This was the Treatment Action Campaign’s litigation – represented by the LRC – to secure nevirapine, and ultimately anti-retroviral drugs, for people living with HIV/Aids in South Africa.

Geoff said that he saw the Norms and Standards case as “a latter-day TAC”, recalling that “it was fundamentally similar, and I remember having that discussion when people came to see me, in the campaign on the ground and the nature of the issue. It just felt like the TAC”.

EE has specifically constructed its vision in the language of the law and the Constitution, but of course this is not – and should never be – the only language in which we dream of a better future.

For example, some economists are today using their language to imagine a different society. In his recent book, The Economy on Your Doorstep, Ayabonga Cawe calls on us to “look beyond the now, the current economy on your doorstep, and reach out to a humanity that lies dormant in all of us.” He builds a comprehensive, practical vision for that humanity – in the language of economics. For Yoliswa, music, too, was a language in which to imagine a different society. Law, though, has certain qualities when it is a language in which to construct a vision.

EE has opted for rights-based struggle. However, litigation for EE is always a last resort. Beyond the litigation that I am focusing on today, EE has engaged in many daily struggles that include school safety, corruption in schools, improved school governance, discrimination, LGBTQ+ rights. These struggles, though not waged in courtrooms, are waged by EE on the ground in their interactions with school principals, the provincial education departments, the media, and so on, in defence of rights.

Author Arundhati Roy speaks at the 3rd Annual Norman Mailer Center Gala at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel on 8 November 2011 in New York City. (Photo: Joe Corrigan / Getty Images)

EE does not stop at theoretical critiques of the law, but puts the law to use as a tool of struggle. The Indian path-breaking activist intellectual, Arundhati Roy, in her powerful recent collection of essays, Azadi (Penguin, 2020) (which means “freedom” in Urdu – and is the rallying call for freedom in Kashmir and for the women’s movement in India), captures the need to translate vision into collective action. She says:

“To listen to accounts of suffering only in order to sympathise is not political. Now that we have listened, we must act. Quickly, cleverly, and furiously.” (at 239)

This resonates strongly with EE and Yoliswa’s approach to activism. EE acts.

So these five features of EE’s approach really stand out for me – building the movement; articulating a positive vision for society; building technical expertise and an evidence base; solidarity; and using the Constitution and the law as one tool of struggle.

Equal Education members march to the Department of Basic Education’s offices on 17 June 2013 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

The education provisioning struggle and its impact

What has the struggle for education rights by EE and its allies produced in South Africa? What has been its impact?

In order to answer that, we need to have a framework to identify all the effects of that struggle, going beyond the victories on paper.

In my research, I propose a typology of three kinds of impact – legal, material and political impact. Legal impact is the effect that law-based struggle has on the law itself, such as the recognition of new rights or duties. Material impact is the tangible change on the ground, including making things happen (or stop happening) or seeing money be paid. Political impact is all about power – the power associated with people, ideas and institutions – and it includes, for example, shifting the national discourse or government policy priorities.

In my PhD thesis, I looked not just at Norms and Standards but also at the litigation to eradicate mud schools and to secure school furniture, teachers, textbooks and scholar transport. This work was done by EE and the EELC, the LRC, SECTION27 and Centre for Child Law, with different organisations leading different cases. I have investigated the impact of all of this. I cannot share all of that today. I will focus on Norms and Standards, but it is important to remember that it was part of a broader collective effort to realise the right to education.

So what has been the legal, material and political impact of the Norms and Standards campaign?

Legal impact

The most significant legal impacts were articulating the content of the right to a basic education and clarifying the state’s duties.

The Norms and Standards litigation established that the substantive content of the right includes safe and adequate school infrastructure, alongside other cases confirming that the right also includes teachers (and non-teaching staff, including administration, security and maintenance), textbooks, furniture, scholar transport and school nutrition.

In addition to confirming the right’s high-level content, the litigation contributed to developing the detailed content, concretising the right. The Norms and Standards prescribe minimum standards for, among other things, accessibility for people with disabilities, school sizes, classroom size, electricity, water, sanitation, libraries, science laboratories, sport and recreation facilities, communication facilities, and perimeter security and school safety. They also set timeframes for compliance – periods of three, seven or 10 years from the date of publication, or by the end of 2030, for different aspects (reg 4(1)(b)).

The three-year and seven-year periods have already passed, so government is obliged, in principle, to have met these targets. The 10-year deadline expires now, in 2023.

The litigation also developed the state’s duties under s 29(1)(a) in three important respects – actual provision, immediate realisation and universality. The cases confirmed that government has an obligation actually to provide the things that make up the content of the right, not just to produce a plan. The cases reaffirmed the position that the right to a basic education is immediately realisable and, unlike the other socio-economic rights, not subject to progressive realisation and available resources. Finally, the cases confirmed that every learner is entitled to every input, making the right universal.

Material impact

The material impact of Norms and Standards is sprawling, extensive and contested. But, to use one government source – the National Education Infrastructure Management Systems reports – between 2011 (before the Norms) and 2020, the following progress was made. The number of public schools with no water supply was reduced from 2,401 schools to zero schools. The number without electricity was cut from 3,544 to just 117 schools. The number of schools with no sanitation at all went from 913 schools to zero. The number of schools with only pit latrines went from 11,450 to 3,164.

These numbers are disputed, including by EE and the EELC, which do their own monitoring. But even accepting some margin of error, they show major progress within a decade.

Political impact

The political impact of Norms and Standards – alongside other strategies and developments – has seen a shifting of national discourse, in which education rights and specifically school infrastructure have gained prominence. In the process, government priorities have shifted, as seen initially in national budgets and state of the nation addresses. The litigation also contributed to movement-building, community mobilisation and strengthening civil society collaboration.

More than any other litigation or campaign, it was EE’s Norms and Standards work that contributed to these changes. And EE has grown, matured and increased its reach during that time. From being derided on the Department’s Twitter handle and threatened with arrest during night vigils outside Parliament, EE fought to literally secure a seat at the table, its leaders being invited to meet the Minister’s team regarding the Norms and Standards process.

It is clear, then, that the Norms and Standards campaign and the other litigation streams that ran alongside it contributed to significant legal, material and political impact.

The impact of the work of EE and its allies over the last 15 years provides a powerful empirical response to arguments that activist litigation offers nothing but a “hollow hope” for social change.

EE’s work has received international attention. For me personally, EE inspired me twice to follow a life path – first, to take up education rights cases; and later to study the impact of a decade of struggle for education rights in my PhD at Oxford. While I was at Oxford, another student completed a PhD entirely focused on EE as a movement. EE’s Norms and Standards campaign is also taught at Columbia and New York Universities. Word is travelling, as it should.

When asked in an interview by the Mail & Guardian what she considered to be EE’s greatest achievement, Yoliswa did not mention the changes to the law, nor the building of new schools or sanitation; nor putting education at the heart of our political conversation. No. This was what she said:

“Equal Education’s biggest achievement has been the development of a core base of active, engaged, thoughtful and disciplined young people who serve as leaders in their families, communities and schools. Equal Education achieved this through steadily educating our learner membership through weekly youth group meetings where politics, social issues and global issues are presented and discussed.

“This core base of young leadership also develops and leads the campaigns around education that Equal Education runs. For the first time, those who run Equal Education’s youth group and youth development work are graduates of the same process. In this sustainable turnover and creation of a vibrant, positive and active youth leadership base lies Equal Education’s biggest achievement.”

(Written responses by Yoliswa Dwane to Sibongile Nkosi, Mail & Guardian journalist, dated 12 October 2011. Email on file with author.)

This, for Yoliswa, was the greatest cause for hope. Just as many learners in the Norms and Standards struggle knew that they were doing it not for themselves but for their brothers and sisters, because they knew the change would not come soon, so too did Yoliswa know that the future of the struggle would lie in the hands of EE’s young members, its future leaders.

In 2013, she said, “I was very pleased to have been part of a team that drove the campaign for Norms and I believe that it is going to be a good legacy to leave behind”.

Hanging in my own office at Seri in Braamfontein is a large framed poster. At the top is a quote from former President Mbeki in 2004 promising that by the end of that year there would be no learner learning under a tree or in a mud school. Underneath is a photo of Nomandla Senior Primary School in the Eastern Cape taken in 2012 – a semi-collapsed classroom built of mud and poles with an asbestos roof peeling off. The poster was signed by Yoliswa and other EE leaders with a handwritten message: “Jason, thank you for fighting for Equal Education.” A year after EE sent me the poster, Nomandla Senior Primary was finally rebuilt.

Equal Education members march to the Department of Basic Education’s offices on 17 June 2013 in Pretoria, South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

Lessons for today’s struggles

I have shared something of the education rights struggle over the last 15 years, with EE at the heart of it. I have tried to draw out the distinctive features of EE’s approach to activism and law. Before I end, I want to say something about what lessons this has to offer for the other major struggles facing South Africa today.

The first key lesson, highlighted by EE’s approach to solidarity, is that of intersectionality. The major struggles facing us today are deeply intertwined, inseparable. I want to mention just three contemporary struggles – the fights against patriarchy and gender-based violence; the pursuit of economic justice; and the resistance to xenophobia.

All of these struggles have been encountered by learners, and by EE. In the Norms and Standards case itself, girl learners told us how the lack of sanitation particularly affected them, putting them at personal risk having to relieve themselves in the fields and forcing them to miss school when they were on their periods.

All the learners and school communities told us how poverty and hunger exacerbated the situation at schools.

Understanding this, EE and SECTION27 went to court to secure school nutrition during Covid. And recently, EE, the EELC and others have bravely confronted xenophobic attempts to exclude migrant children from our schools – trying to enforce a court victory by the LRC that confirmed that no child, regardless of status, may be excluded from school.

So all these struggles have touched the education struggle, overlapped with it. But these struggles do not always intersect in obvious ways. We must never forget that they are nevertheless deeply connected, even if they do not, for example, enter our schools directly.

Even if we realise the dream of decent school infrastructure at every school in the country, that will count for little if the patriarchy reigns unabated and girl learners continue to be exposed to discrimination, harassment and assault.

Similarly, state-of-the-art schools will count for little if food insecurity continues to rise, learners go hungry, and then cannot sustain livelihoods when they leave school.

And what will fine school buildings be worth if we have allowed craven thugs or government officials to chase away children and teachers from other African nations? My point? The education rights struggle is inseparable from the other major struggles that we now face. The answer? Solidarity, as is typical of EE’s approach as a movement. This does not mean that a movement like EE should be at the forefront of every struggle, but rather that a progressive movement needs to throw its weight behind those who are fighting the patriarchy, fighting for economic justice, resisting xenophobia.

Over the last two or three years, civil society has increasingly come together, recognising the interconnectedness of the struggles in which we are engaged. Several major gatherings have brought together hundreds of activists, social movements, community-based organisations and NGOs. These have included the Social Justice Assembly, the NGO Consultative Conference convened by the Kagiso Trust and the regular gatherings convened by Defend Our Democracy, Rivonia Circle and the Kathrada Foundation.

There is a common vision and sense of urgency emerging from these conversations, calls for a “new UDF”, for solidarity across silos, for direct confrontation with structural economic injustice, patriarchy, racism and xenophobia, and to stand together against State Capture, corruption and attacks on our constitutional democracy.

Equal Education is already playing a leading role in this collective activist space. The distinctive features of EE’s approach to activism, including how it uses the law and the Constitution, should be central to any national movement that emerges.

We will look to EE’s leaders of today and tomorrow, following in Yoliswa Dwane’s footsteps, to take us forward.

I thank you. DM/MC

Jason Brickhill holds an LLB from the University of Cape Town (magna cum laude) and an MSt in International Human Rights Law (with distinction) and DPhil from the University of Oxford. He has appeared in all the South African courts, the courts of Namibia and various commissions of inquiry and arbitrations. Jason served as law clerk to Justice O’Regan at the Constitutional Court, and worked at Bowmans and the Legal Resources Centre, where he was Director of its Constitutional Litigation Unit. He is currently Director of Litigation at the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (Seri). Jason has published widely. He is Editor-in-Chief of South African Constitutional Law (Juta), external examiner (postgraduate) at the University of the Witwatersrand and an Honorary Research Associate at the University of Cape Town. He teaches international human rights law and supervises research dissertations at master’s level at the University of Oxford.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.