APARTHEID RATIONALE OP-ED

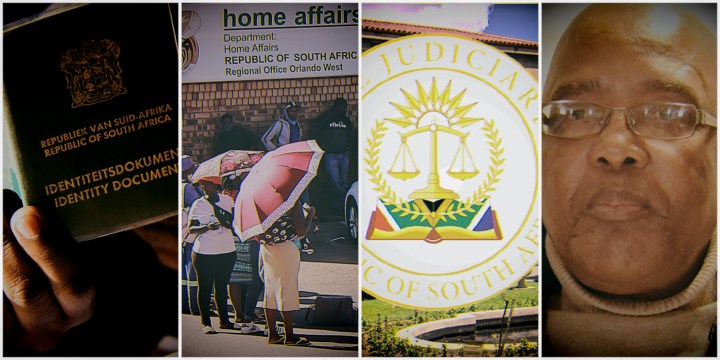

Key court challenge to powers of Minister of Home Affairs stripping South Africans of their citizenship looms

An apartheid-era relic which allowed the minority white government to strip Bantustan residents and exiled freedom fighters of their South African citizenship is being challenged in the Supreme Court of Appeal.

Believe it or not, even in 2023, many South Africans have their citizenship taken away against their will. The Supreme Court of Appeal is about to consider the constitutionality of a provision which authorises this unacceptable denial of one’s birthright. We hope the court holds this outdated provision to be invalid.

Section 6(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act stipulates that a South African citizen is automatically stripped of their citizenship if they acquire the citizenship of another country unless they first seek and receive permission from the Minister of Home Affairs to do so.

Disturbingly, this provision is a relic of the apartheid-era 1949 Citizenship Act. Despite the sham nature of the Bantustan “homelands”, the apartheid government regarded black South Africans as holding the citizenship of another state — that allowed it conveniently to denationalise many of them.

Moreover, many freedom fighters who opposed the apartheid regime had been forced into exile and acquired the citizenship of other countries: this provision enabled the government to strip them of their South African citizenship.

This, in our view, is part of the historical backdrop behind the enactment of a strong citizenship right in the Constitution: section 20 proclaims in no uncertain terms that “no citizen may be deprived of citizenship”.

That right was one of the bases for a constitutional challenge brought by the Democratic Alliance to section 6 in the North Gauteng high court. It was argued that this provision lacked any clear rationale and that it violated section 20 and several other constitutional rights. Disappointingly, the high court upheld the provision in a deeply flawed judgment which, we hope, will be overturned by the Supreme Court of Appeal.

Fundamentally, it is hard to understand the purpose of such a provision in South Africa’s constitutional democracy: why should citizens be deprived of their South African citizenship if they acquire the citizenship of another country? In its court papers, the government suggested that people who did so voluntarily indicate that they wish to be deprived of their South African citizenship. This reasoning is unpersuasive both empirically and legally.

Empirically, it is clear that many South Africans who lose their citizenship this way are profoundly distressed and in no way intended to renounce their citizenship.

In the court papers, a Mr Plaatjes describes his experience of falling in love with his wife while on a working trip overseas. To accommodate her desire to live near her family, he moved to the UK and eventually naturalised. To his horror, when he came to renew his passport, he was told that he had lost his South African citizenship.

He expresses clearly his deep commitment to South Africa and his concern about how being stripped of his citizenship may separate him from his South African relatives.

An online survey conducted by the applicants found that 87% of those who have automatically lost their citizenship had not known about section 6, and that only 3% intended to forgo their citizenship.

Legally speaking, the provision is also clearly flawed. The Citizenship Act makes express provision for the voluntary renunciation of citizenship. Therefore, there is no reason to take someone’s citizenship away unless they expressly renounce their citizenship.

It may be responded that section 6 does allow South Africans to retain their citizenship through applying for the Minister of Home Affairs’ permission. Yet, it appears that affected South Africans were either unaware of this arcane provision or had been provided with flawed legal advice (as in the case of Mr Plaatjes).

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

In our view, section 6 is constitutionally invalid also due to offering no criteria on the basis of which the minister should decide citizenship retention applications. The Constitution requires that citizens know in advance which criteria are utilised by a minister when making a decision: the failure to provide guidance to citizens as to the grounds for approval or refusal is alone sufficient grounds for a declaration of unconstitutionality.

Most importantly, the section 20 constitutional right proclaims that no one should be deprived of their citizenship unjustifiably. Given that the voluntary renunciation rationale falls flat, the High Court judgment alluded to the troubling view that loyalty to South Africa excludes loyalty to another country.

As we mentioned, the provision was included in the 1949 Act when multiple citizenship was a far rarer phenomenon, with countries conforming to the notion articulated in the 1930 Hague Convention that every person should have only one nationality.

Since then, a clear global trajectory points towards increasing tolerance of multiple citizenships: today, most countries do not require citizens to choose between an acquired citizenship and their citizenship of birth. It is thus increasingly recognised that loyalty to one political community in no way precludes loyalty to another.

The reasons for this change lie in globalisation and the fact that for an increasing number of people, mobility across borders is a feature of their lives. Employment opportunities may arise in countries far removed from one’s place of birth or one may meet a partner from another country and seek to relocate.

For some, new citizenships may be acquired for instrumental reasons: ease of movement, as Covid-19 national restrictions have demonstrated, often requires applying for citizenship.

For others, a new citizenship may have a deeper personal significance, representing a desire to belong to the polity in which one resides. What acquisition of a new citizenship does not mean is that an individual wishes to lose the citizenship of their country of origin, to which they may retain intense and meaningful ties.

Whether desirable or not, citizenship retains its significance as a vanguard of two critical rights. The first is the right to vote and fully participate politically in the state’s affairs. The second is the right to enter the state’s territory and to remain therein unconditionally.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted how many countries temporarily restricted entry only to their citizens. Given this legal reality, it stands to reason that South African citizens living abroad may wish to acquire another citizenship without manifesting disloyalty to South Africa.

Loss of one citizenship is also not compensated for by the acquisition of another citizenship: this is because each citizenship serves, within its respective political community, as a marker of legal status, rights, and belonging. Loss of South African citizenship entails the loss of tangible rights, such as the right to vote and to enter and remain in the republic, which are exercised by South Africans living abroad.

Moreover, by being involuntarily stripped of their citizenship, citizens lose parts of their identity and sense of belonging, becoming at once a “foreigner” in the place of their birth.

We believe an apartheid-era provision mandating automatic loss of South African citizenship due to acquiring another citizenship has no acceptable rationale and unjustifiably strips citizens of many fundamental rights. It has no place in South Africa’s constitutional democracy — we hope the appellate courts will consign it to the dustbin of history. DM

This opinion piece draws on our case-note in the South African Journal on Human Rights (available on open-access here).

David Bilchitz is Professor of Fundamental Rights and Constitutional Law at the University of Johannesburg and the University of Reading; Director of Saifac; Vice-president of the International Association of Constitutional Law; and a Member of the Academy of Science of South Africa.

Reuven (Ruvi) Ziegler is Associate Professor in International Refugee Law at the University of Reading and a Visiting Professor at the University of Johannesburg.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A well-articulated article. Yet another example of the DHA’s fundamental incompetence, to say nothing of their extreme xenophobia. When will they realise that not only is “no man an island”, but that equally, no country can be isolated?

As a country, RSA needs all the skills and resources that it can get, as the “brain drain” continues and we bleed all our best people elsewhere.

While I agree widely with the premise of the piece and the limiting of the States powers with regards to citizenship, but the process of naturalisation is in fact a voluntary resignation of your citizenship, provided you are older than 18, and I suspect this is the case everywhere. I lost my German citizenship because my mother naturalised me, and I have been unable to convince the Germans to reinstate me, despite me being under 18 at the time. Mr Plaatjes made a mistake. He didn’t have to be naturalised, and should have realised the consequences of such an act.

So I, a naturalised South African by marriage, am a citizen of both the UK and Ireland, hold current passports for the same and South Africa, and have a right to citizenship that people born in South African previous homelands may not? What utter nonsense is that?

In 1984, I acquired dual citizenship – SA which I had since birth and Italian by marriage. I had written permission from the Department of Home Affairs in Pretoria on the basis of it facilitated my business travelling. In the 1996 I lost my SA ID card and received a replacement one. In the 1999 election, I went to vote and presented my ID. I was told I could not vote – I was a non-SA citizen. My ID card said so – but I hadn’t even looked at it when I received it. It cost me R22,000-00 in those days to get legal advice and rectify the position. Apparently, my letter from the DHA was signed by the deputy minister, not the minister. If this happened today, I wouldn’t fight it. That SA ID card is something of an embarrassment – it’s just not what it was in the ’90s.

Mr Rasch, your argument sounds more a case of sour grapes, then any commitment to the fact of involuntary loss of citizenship. You state clearly that you actually believe in the ability to have dual citizenship. You applied for German citizenship. If you were born there, it should be (as recognised by you) a birthright. Almost every country, including Germany and South Africa, recognises the right to dual citizenship.

I have dual citizenship and use my non-SA passport purely for flexibility and ease of travel to countries in Europe and Asia where my second passport has largely visa-free access. It saves me (and South Africa) thousands of Rands a year in not paying a foreign government for a visa, and it saves me thousands that I would lose standing in queues getting visas.

It’s not about fealty to another country, it’s simply a practical thing to be able to use on my business and holiday travels.