ANCIENT HIGHWAYS

Pioneering conflict-avoidance study asks elephants what works for them

Elephants created Africa’s first highways and still remember them. It’s when we block them that trouble with humans begins.

Elephants are long-distance hikers, moving with the rains and seeking out greener pastures. Pathfinders among them communicate the best routes to follow, irrespective of national borders, fences or farms which try to block them. Because we’re not aware of this, says a study just released, it results in human-elephant conflict – often with tragic results on both sides.

There is a solution. The research by the NGO Elephants Alive says that by understanding these elephant highways and the sorts of food that attract or deflect them, indigenous farmers can avoid trouble and increase tolerance of their seasonal migrations.

For 25 years the NGO has been tracking pathfinding elephants across southern Africa, trying to understand why they take the routes they do. It found that they trek along ancient pathways which take them through human-dominated landscapes. These journeys can cover huge distances, often through several countries.

Human-elephant conflict occurs when humans overlap with traditional elephant highways. (Photo: Maurice Schutgens for Elephants Alive)

Thirty years ago, southern African states had just more than 20% of Africa’s continental elephant population. Because of excessive poaching in Central and East Africa, these southern states have now become their last stronghold, with more than half of the continental population. Of the remaining elephants, 76% are found in populations moving over more than one national border.

Keystone species

Because elephants are keystone species – meaning they enable other species’ survival within the ecosystem – principal researcher Dr Michelle Henley writes that it’s imperative that these corridors are maintained.

“Failure to curb human-wildlife conflict where both humans and elephants intersect – if left unaddressed – may result in the linkages being closed off completely.”

Conflict is rapidly increasing as elephants are compressed within their natural range alongside burgeoning human populations, resulting in damage, economic losses, injuries and death of people and elephants.

Crop raiding by elephants represents a common form of conflict and could be driven by a lack of microminerals that are not available in the protected areas within which they are expected to remain. This is a problem that poses serious challenges to wildlife managers, local communities and the elephants themselves.

Understanding elephant movements along these wildlife corridors shows where connectivity between protected areas is most needed and where human-elephant conflict mitigation would be most effective across a large landscape.

Connecting protected areas across political borders while building more sustainable rural economies around corridors chosen by elephant movements is of prime importance, say the researchers.

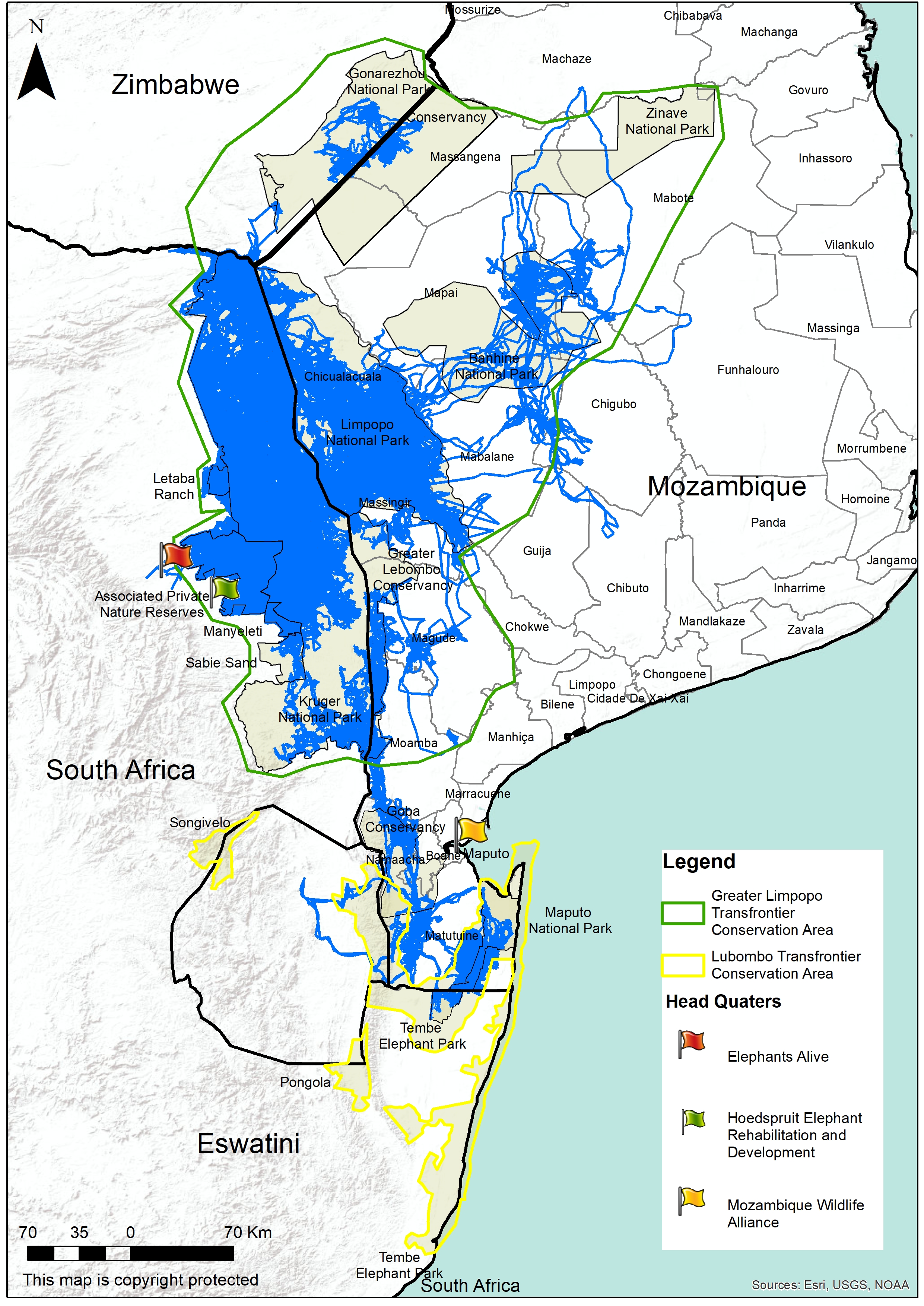

The transboundary movements of elephants between South Africa, Mozambique, Eswatini and Zimbabwe (1998-2022). (Source: Elephants Alive)

These highways are remembered by what Henley calls pathfinding elephants which were collared and watched using satellite technology over many years. Using this information, highway “maps” have been drawn over time. Their movements can cover about 3,000km across the Greater Limpopo and Lebombo Transfrontier Conservation Areas and include South Africa, Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Eswatini.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Having discovered the migration routes, the researchers set about trying to figure out what to do to reduce conflict. One strategy involved providing habituated elephants with a “cafeteria” of plant types to find out what foods they preferred or avoided.

The researchers worked out which plants with the potential food, essential oil, medicine and/or bee-fodder value were avoided by elephants. Propagating these as soft barriers around food crops, they say, would ward off marauding elephants, provide new economic opportunities and increase food security.

Beehive fences are effective because elephants are terrified of bees. (Photo: Elephants Alive)

Another solution was using “beehive fences” (elephants are terrified of bees) with suspended hives and tripwires that shook them, causing the bees to buzz angrily. This works better than hard barriers such as electric fencing which often threaten connected landscapes if not strategically placed around local cluster crops. They’re expensive and ineffective if not maintained once elephants learn to breach them.

Rapid response units

Another strategy was the deployment of rapid response units to scare away crop-raiding elephants before they could do any damage. This was trialled by the Mozambique Wildlife Alliance under Dr Carlos Lopes Pereira, with great success.

It soon got the support of communities using non-lethal, low-disturbance methods and a basic understanding of elephant behaviour. “This is a community-based response that can be replicated in many places, resulting in increased tolerance [and] less damage to crops and people’s livelihoods,” said Pereira.

According to the study, elephants moving along corridors across human-dominated landscapes depend on tree cover where they can hide during the day. Creating these vegetation “stepping stones”, says the study, could be monetised as carbon credits.

“If elephants are to survive,” said Henley, “we must invest in scientific knowledge to deepen our understanding of their movements and spatial requirements in combination with understanding the socioeconomic needs of the people that share the landscape with them”.

According to Dr Lucy King, head of the Human-Elephant Co-existence Programme for Save the Elephants, we are running out of time to protect both the future of elephants and the safety of communities living side-by-side with them. “By investigating novel crops that are unpalatable to elephants as well as being bee-friendly by providing sustenance to bees living in protective beehive fences, the researchers have taken an important step towards seeking human-elephant coexistence.”

The study is a pioneer in including elephants in the “conversation” about their own future. DM/OBP

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What a fascinating article. My husband and I travelled through the ‘Futi Corridor’ in October of 2021 and one of the species that we did see quite a lot of was elephants which I’m beginning to understand is critical to the entire echo system. They did seem a lot wilder that the elephants one typically encounters in SA parks.

Wonderful study. Hopefully will lead to greater attempts to connect our wild spaces.

Fantastic article and such an interesting topic to research.