GEOPOLITICS

Vladimir Putin’s grand illusions crumble into ashes in brutal theatre of real war

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine fits into a larger picture of a delusion about the nature of Ukraine’s relationship with Russia. Delusions can, of course, have painful, consequential outcomes — and increasingly horrific ones.

Over the past few years, events leading up to, but now including the current fighting in Ukraine, have forced us to revisit our previous studies of Russian and Eastern European history and politics. This came just as we had begun to believe the Cold War was finally over, and we could move on to examine other critically important issues.

Now, of course, classic works such as Leonard Shapiro’s memoirs of the Russian Revolution and civil war have joined our reading — and rereading — shelf, along with new works such as Orlando Figes’ history of Russia, Serhii Plokhy’s rich saga of Ukraine’s historical trajectory, Anne Applebaum’s years of reportage on the borderlands of Eastern Europe, and dozens of other thoughtful essays on the political and military aspects of the current crisis. The literature about the misjudgments (and near catastrophe) of the Cuban Missile Crisis have become part of our reading plan as well. We are no longer reading anything about the halcyon days that have come about from the end of the Cold War.

Members of the Ukrainian military, 59th Brigade, service their tanks and take on new supplies before moving to a new position on 23 November 2022 in Kherson, Ukraine. (Photo: Chris McGrath / Getty Images)

Now, however, the world is closing in on the first anniversary of Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, its next-door neighbour. Contained in that simple statement are two critical understandings that must be brought into sharp focus. The first is that the Russian attack was, at its heart, an unprovoked one, rather than any kind of justifiable, defensive gesture. The second is that Ukraine is a sovereign neighbour of Russia, rather than some kind of illegitimate, breakaway province, operating at the behest of shadowy foreign forces. Instead, Ukraine deserves to be allowed to carry out its foreign relationships in the same way as all other sovereign nations. (This understanding of sovereign equivalence among nations has deep roots reaching back to the 1648 Westphalian settlement that ended the Thirty Years’ War.)

It follows from those two basic understandings that any Russian policy and its military and diplomatic acts designed to avenge some kind of great wrong that has been committed against an aggrieved Russia, and that Ukraine is not a real nation and only deserves a subsidiary place in Vladimir Putin’s imagined greater Russia, must be dismissed as dangerous delusions. Nevertheless, these delusions have been delivering consequences since 24 February 2022. But, with those understandings clearly set out, we can speculate on the future of this conflict — and what it is likely to mean for the rest of us.

The illusory provocations

Begin with that first understanding — the nature of those illusory provocations. Back in 1990-91, when the old Soviet Union was collapsing into 15 sovereign nations, beyond the special cases of the three Baltic republics, Ukraine moved early on to declare its independence from a disintegrating Soviet Union.

Once secured, Ukrainian independence was embraced by international organisations. Moreover, complex negotiations were carried out in 1993 that brought about the military denuclearisation of the country (numerous ex-Soviet strategic nuclear weapons had remained on-site inside Ukrainian territory after the breakup), and the sharing of naval forces stationed in Sevastopol on the Crimean Peninsula — now part of independent Ukraine. Moreover, Russia signed on to a complete acceptance of its territorial integrity and full sovereignty of that nation through the Budapest Accord in 1994.

Ukrainian serviceman Oleksii Hodzenko, alias Godzilla, press officer and marine, walks in the trenches at a frontline position held by Ukraine’s 503rd Detached Marine Battalion on 7 February 2022 near Verkhnotoretske, Ukraine. (Photo: Gaelle Girbes / Getty Images)

(An often-forgotten footnote in history is that Ukraine had been an original member of the UN since 1945 due to Stalin’s insistence that if Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa could be UN members and part of the British Commonwealth, then the notionally independent Belarusian and Ukrainian republics should similarly gain the same treatment.)

It is true that at the time of the Soviet breakup, there was an early understanding between the Americans and the Russians that Nato troops would not be stationed permanently on the territory of what had previously been East Germany, although the newly unified Germany would continue as a Nato member. At the time, nothing had been said about the former Warsaw Pact nations such as Poland or the others, or even the three Baltic republics, all of which were still just potential future members of Nato.

From the perspective of those nations, having finally freed themselves from decades of Soviet domination, self-interest and national sentiment led them — and eventually others such as Albania, Montenegro and Macedonia — to seek the protective embrace of Nato membership. Those accessions to Nato evinced few protests from Russian leaders, then. Moreover, there was no real drumbeat among US policymakers to enlist these nations into the alliance. In fact, there had been significant opposition on the part of some in the US Congress to support nations like Romania in their decisions to join Nato. To those critics, such decisions could easily be read as expanding US security commitments beyond the nation’s reasonable capabilities. (Romania did finally gain support from the US Congress in 2004.)

While some US officials had — almost off-handedly — smiled upon the idea that Ukraine would also ultimately join Nato, there has never been a formal application or an invitation to do so. At the time, it should not be forgotten, Russian leaders had also punted the idea that their nation might wish to join Nato as well. Nevertheless, it is also correct that influential figures such as former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, among others, had argued Ukraine should not move towards seeking affiliation with Nato.

Ukrainian tanks positioned on the frontline on 25 December 2022 in Donetsk, Ukraine. (Photo: Pierre Crom / Getty Images)

Now, of course, the irony is that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has finally provoked Europe’s two traditional neutral states — Sweden and Finland — to apply formally for membership in Nato. Those applications are awaiting full ratification by all of Nato’s members, although Turkey says it has issues with Sweden’s membership because the Turkish government is unhappy with Sweden allowing Kurdish groups to operate freely in Sweden, arguing such groups are actually terrorist organisations.

Regardless of Sweden’s situation, one frequent argument by the Russians has been that if Ukraine were to apply and be accepted, their direct border with Nato nations would be much longer, and thus serve as a threat to Russian security. Instead, regardless of Ukraine’s ultimate circumstances, as a direct result of their invasion, the Russians have effectively achieved an approximate doubling of their direct border with Nato, once Finland’s membership is confirmed.

Given Finland’s quite credible military capabilities, for Russia, this has become an extraordinary cutting off of one’s nose to spite one’s face as a quixotic foreign policy accomplishment. Further, that result is separate and apart from the increased, more intensive training exercise regimen between the US and other frontline nations’ militaries, due to the very fears provoked by the Russian invasion — as yet another obvious response to that invasion.

In truth, more than an interest in Nato membership, the real deal for Ukraine following the 2014 Maidan Revolution had been the hope of an eventual opportunity to gain membership, or at least formal association, with the EU, as part of its drive to modernise its economy, reform its economic and financial structures and further integrate that economy with the West. These became increasingly important goals for Ukraine once the Russian sympathiser, acolyte (and major kleptocrat) Viktor Yanukovych had been driven from office in a popular uprising.

A tank in the centre of Bakhmut, Ukraine on 24 December 2022. (Photo: Pierre Crom / Getty Images)

By contrast, the real Russian objective, vis-à-vis Ukraine, given its argument that Ukraine was not a viable, independent nation, has been to return that country to the circumstances as a subordinate state within Russia’s own self-described sphere of influence, as one more part of its “near abroad” — or, ultimately, even to manoeuvre Ukraine into rejoining a refashioned Russian-led commonwealth. Before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Ukraine had, of course, been a major part of the Soviet Union’s industrial and technological power base.

The second grand illusion

This leads us to the second grand illusion that has been the apparent motivation for Russia’s (or more properly, Putin’s) road to invasion. That argument is that Ukraine is an illegitimate state, founded as a cohesive political unit by Lenin in 1922, which was a serious mistake. Thus, it is a vital mission for the Russian leader, in his view, to lead that wayward state back to where it really belongs.

Such a mission would help fulfil the greater Russian world’s historical destiny from 1,000 years ago, right back to the founding of the ancient Kyivan state of Rus (by those wandering Vikings, or Varangians, in tandem with the local tribes). That was the legendary origin point for the three Slavic nations of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine, a society that has been tested by foreign invasions beginning with the Mongols and Tatars, then the Poles, Swedes, French and Germans in succeeding years — and is now tested by Nato.

Slavian, a former Russian special forces sergeant, pauses in a frontline trench around 150m from Russian positions on 27 October 2022 in Zaporizhzhia oblast, Ukraine. (Photo: Carl Court / Getty Images)

In contrast, Yale East European scholar Timothy Snyder recently wrote on this illusion in the September/October issue of Foreign Affairs, noting:

“In an essay published in July 2021, Putin argued that events of the tenth century predetermined the unity of Ukraine and Russia. This is a grotesque as history, since the only human creativity it allows in the course of a thousand years and hundreds of millions of lives is that of the tyrant to retrospectively and arbitrarily choose his own genealogy of power. Nations are not determined by official myth, but created by people who make connections between past and future. As the French historian Ernest Renan put it, the nation is a ‘daily plebiscite’. The German historian Frank Golczewski was right to say that national identity is not a reflection of ‘ethnicity, language, and religion’ but rather an ‘assertion of a certain historical and political possibility.’ Something similar can be said of democracy: it can be made only by people who want to make it and in the names of values they affirm by taking risks for them.

“The Ukrainian nation exists. The results of the daily plebiscite are clear, and the earnest struggle is evident. No society should have to resist a Russian invasion in order to be recognized. It should not have taken the deaths of dozens of journalists for us to see the basic truths that they were trying to report before and during the invasion. That it took so much effort (and so much unnecessary bloodshed) for the West to see Ukraine at all reveals the challenge that Russian nihilism poses. It shows how close the West came to conceding the tradition of democracy.”

Response of the West

But, slowly and cautiously, and unexpectedly, the West has increasingly responded forcefully through the provision of an ever-increasing supply of hi-tech weaponry, including, but not limited to, anti-missile defence systems, armoured fighting vehicles, electronic capabilities, and most recently, decisions on the part of several Nato members to transfer modern battle tanks to Ukraine as well. While all of this materiel assistance has been very important, the superior strategic vision of Ukraine’s military in its hour of testing, its innovative and local tactical command, the growing capabilities of Ukrainian troops generally, and, above all, the way the nation as a whole has coalesced into its national struggle for existence have made the difference so far.

Collectively, despite being substantially outnumbered, these factors have allowed the Ukrainians to repel Russian advances against Kyiv, Kharkiv and Kherson, and to — so far — largely hold Russian regular troops and those mercenary Wagner forces along their eastern line of advance.

Russian conscripts attend military training at a ground training range in the Rostov-on-Don region in southern Russia, 21 October 2022. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Arkady Budnitsky)

The Russians have largely fallen back on launching rockets, missiles and drone strikes against the nation’s apartment buildings, hospitals, schools, other public buildings and — crucially — electrical, water and heating infrastructure.

This style of devastating warfare being conducted against civilians across Ukraine is more than a little redolent of the worst excesses of siege warfare down through the centuries, only this time carried out with devastating modern weapons. But such attacks have surely put paid to the idea that Russia’s core objective is in reuniting all of its brother Slavs back into their natural, inevitable commonwealth.

A war of attrition

In the meantime, there are thoughts by many observers that the battle lines are likely to stay largely frozen in place, and that the fighting will harden into a war of attrition rather than one of movement and flexibility. Still, there are also rumours of new ground operations by Ukraine aimed at liberating additional, still-occupied territory, and even breaking the overland Russian connection to the Crimean Peninsula — the territory that was forcibly annexed by Russia back in 2014.

Success in such a movement, besides delivering yet another black eye to Russian military forces, could make it easier, again, for Ukraine to export its grain from Black Sea ports to its increasingly worried, hungry customers in Africa, Asia and the Middle East who are facing much higher prices.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Meanwhile, the Russians — and especially their president — have clearly been embarrassed by their lack of success on the ground. In less than one year of warfare, they are now betting on the skills of their fourth invasion commander. This time around, Putin’s choice has been General Valery Gerasimov, the Russian military’s chief of the general staff — a position roughly equivalent to the US general Mark Milley as chairman of the joint chiefs of staff.

(To this writer, the growing desperation on the part of the Russian president to find the magic commander who can actually win the war, rather than be embarrassed by the failures on the ground, echoes in some ways Abraham Lincoln’s revolving door replacement of his commanders — through three years of fighting — to lead the Army of the Potomac in the crucial Virginia theatre of war. Unlike Lincoln in a different age, however, Putin may not have the time to keep experimenting, given the flow of weapons to Ukraine, the relative lack of popular enthusiasm for this war now that further drafts of new troops are likely, and the growing pinch of the strictures of Western sanctions.)

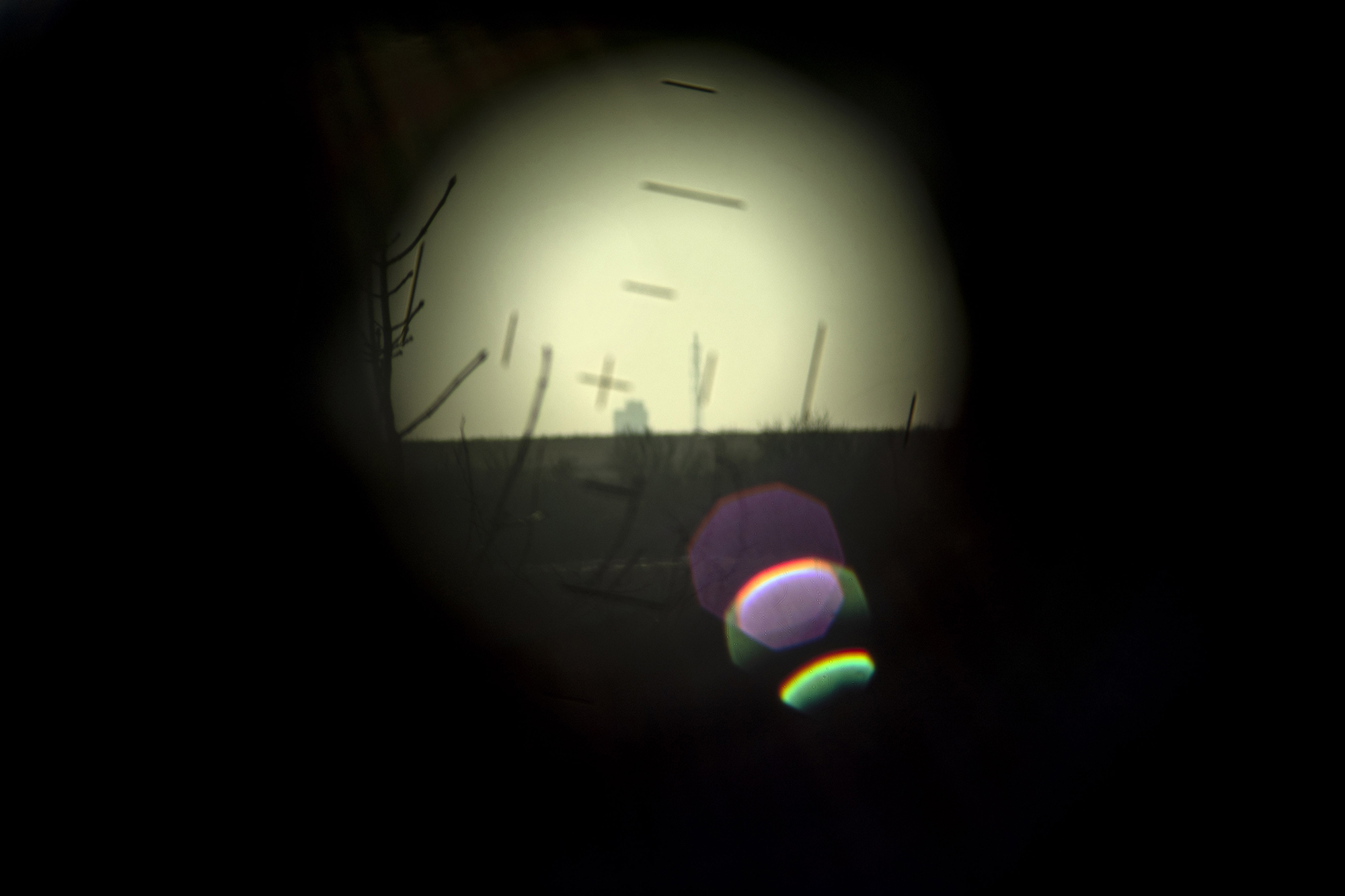

A view of DPR, (Donetsk People’s Republic) rebel positions seen through a scope from a trench of the Ukrainian Army near the village of Svitlodarsk, in Donetsk region on 13 February 2022, shortly before the Russian invasion. (Photo: Manu Brabo / Getty Images)

Looking forward into 2023, little suggests this war will end easily or soon — absent a sudden leadership change in the Kremlin. The Ukrainians appear to have summoned the resolve to maintain their nation, virtually come what may, even as the human losses and the mounting destruction across their country continue to rise.

Meanwhile, so far at least, Putin has given little indication he is prepared to declare victory and bring his armies home, let alone accept any responsibility for the horrendous costs that have been inflicted on a nation he continues to insist is simply a wayward part of his own country.

At least for the time being, Ukraine’s supporters among the Western nations continue to provide the kinds of weapons that are crucial and the training to make sure such equipment is used to its best advantage. Perhaps the real unknown, now, is the way Russians not in the military begin to respond to greater difficulties in their own lives, or how the country’s military (as well as those auxiliaries like the Wagner Group) responds to yet another season of setbacks or worse.

Of course, in government chambers in Washington, London, Berlin, Paris and a range of other capitals, there will continue to be those dire calculations about what circumstances might ultimately provoke Putin to throw caution to the wind (and bet on drawing that one needed card for a royal flush in poker) and make use of a tactical nuclear weapon or two to stave off a real defeat of his ill-fated invasion. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Very insightful article that pretty well sums up events and mindsets. Level headed reporting, free of propaganda and distortion, is very much needed in all parts of the world.

Right. The big mystery is “will Putin use tactical nuclear weapons”? The other big mystery is, what the reaction to Putin’s use of tactical nuclear weapons be? I suggest that Putin’s use of any nuclear weapons will be his own suicide.

A very informative article, definitely worth a read as it goes a long way in explaining the Russian/ Ukrainian history. Amazing that it takes only one man with his personal agenda to cause thousands of deaths…

War must never be celebrated or praised because of its impact on civilians in particular women and children and the massive internal displacement and refugees that goes with the destruction of homes, civilian infrastructure and the entire formal economy. In class terms, it is an attack on the working class of the country and for SACP to celebrate the Russian invasion of Ukraine was proof that they are communist quacks.

The provision of tanks to the Ukrainian military along with the advanced air defence systems will turn the tide of the war decisively. With Canadians having taken a decision to purchase missiles from the US and provide the Ukranians along with the drones will help to shorten the war and end the hostilities. It is when the Russians are hit hard and suffer casualties to the extent that the options left would be to withdraw from Ukraine. This unfortunate option will lead to intense fighting but quickly bring an end to the war in particular a capability that is aerial for Ukraine to be able to attack the bases from where Russia is firing its missiles. We will see if the SACP will be dancing.

That Canadian support for the Ukrainians is interesting. Canada has a huge number of citizens who are descended from Ukrainian immigrants. The Ukrainian language is not a totally uniform across Ukraine. When the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine went independent it did not have a uniform language so chose Canadian Ukrainian textbooks as their standard.

Thank you Mr Spector for the insightful and clear article on the historical and current context of the situation in Ukraine.

Listing selective facts to support a particular position is not new. No mention in the article of the revelations made by former German chancellor Angela Merkel and others about the insincerity and deceitfulness of the Minsk accord or the accelerated NATO military support, training, and armament of Ukraine to serve as a battle ram against Russia. This was a project that has been long in the making. The silence on the past and continued bombardment and attacks on the Donbass speaks loudly. Nothing said about the serious concerns, also captured and reported on by international media, of the growing neo-Nazi establishment and influence in Ukraine or the label of being one of the most corrupt countries in Europe. No mention of the media muzzle put on national and international journalists and media houses. One wonders about the leaning of the Maverick and how it affects perceptions of the truth being defended.