TERTIARY REFORM OP-ED

Transforming universities, one promotion at a time

Transformation of universities has been high on the agenda of higher education in South Africa for a long time. Demands for change preceded democratic elections in 1994. They included widening access for students, orienting the curriculum to suit South Africa’s particular needs and histories and diversifying the staff complement.

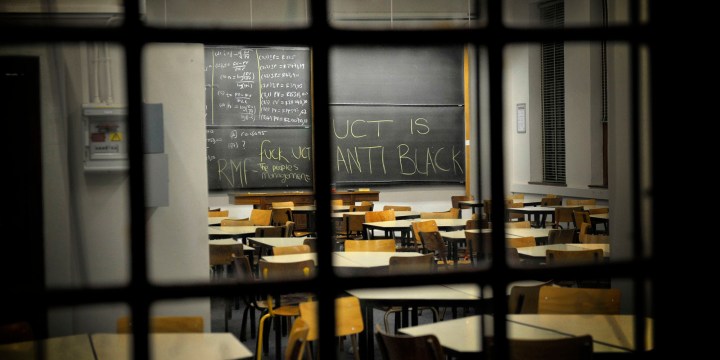

These challenges became more visible after 2015 as a result of the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall movements. The movements highlighted racial inequalities in terms largely of staffing complements at the former white universities as well as critiquing ‘western’ influence on curriculum and calling for decolonisation. The final element of the demand for transformation was for an end to student fees.

The University of Cape Town was the epicentre of this movement from 2015 onward when the Rhodes statue was removed from campus. Separate from student demands there was pressure from the Department of Higher Education and Training (DHET) on the university to correct racial inequalities evident in its staffing complement.

One of the areas that came under the spotlight was the skewed distribution of staff across the academic hierarchy. White male professors predominated the higher echelons. While this pattern had been slowly changing, the university climate generated questions about the fairness of the promotion process.

Questions asked were: Who got promoted? Was the process transparent? Were there bottlenecks in the system that were to blame for the skewed hierarchical distribution (by race and gender)?

Academic promotions are universally a hot issue for staff. With promotion comes more remuneration, more opportunities, more influence, more prestige. All University staff want one day to be called ‘Professor’. The process by which staff get promoted varies but generally involves a rigorous set of steps including applicants writing a motivation, referees providing outside input and various university committees considering each application.

Despite suspicions that UCT’s promotion process was biased against black and female staff, no evidence of bias was found in a careful study that analysed all academic promotions at UCT from 2005 to 2015. (Hassan Sadiq, Karen I Barnes, Freedom Gumedze, Max Price, Robert Morrell (2019) “Academic promotions at a South African University: Questions of bias, politics and transformation”, Higher Education: 78(3): 423-442).

Nevertheless, the issue of promotions remained contentious because of the slow change in the demographic distribution of staff. Black and female staff were under-represented at senior academic levels.

UCT not unique

This situation is not unique to UCT. Many universities are pursuing diversity which is understood as having good representation of minorities in the ranks of the professoriate. The ways in which universities approach this challenge vary. And precisely what ‘good representation’ may mean is seldom specified or agreed upon.

Research has shown that in South Africa, transformation targets are seldom identified making it impossible to know if or when you’ve achieved transformation. (Van Schalkwyk, François B., Milandré H. van Lill, Nico Cloete, and Tracy G. Bailey, “Transformation impossible: policy, evidence and change in South African higher education.” Higher Education 83(3) (2022): 613-630).

Yet there is pressure on universities to demonstrate diversity. Student protests frequently object to the racial and gender composition of staff. Reports in the media highlight this (“Why are there so few black professors in South Africa?”, The Guardian, 06 October 2014).

Under these circumstances, it is tempting to go for a quick fix.

In 2019 Unisa proposed exactly such a quick fix by announcing that ‘race’ would be a weighted criterion in the promotion process, drawing sharp criticism from Jonathan Jansen. “It is, quite frankly, disgraceful and the damage inflicted on a once great university, incalculable”, he said.

A less controversial step has been to operationalise government policy which intrudes into all public institutions. Institutions are held responsible for meeting racial and gender targets in their staffing, and this is often cascaded into employment practices implemented by Human Resource Departments. At UCT a preference for the employment of black South Africans has meant that international staff (those from outside South Africa including many academics from the rest of Africa) and white South Africans may not be short-listed in an initial round of advertising for an academic post.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

This approach can be described as technicist. It relegates merit as the primary consideration and approaches a problem much as a mechanic might deal with a malfunctioning motor car. It has several advantages. It is relatively simple and easy to implement and personal factors are removed from the process. The suspicion is frequently expressed that university appointments are basically on the basis of jobs for buddies.

But there are downsides — groups are excluded from applying and this can lead to a lowering of morale. And it is possible that the best person for the job is not appointed.

Technicism is a managerial approach to a problem. The quality of management is thus a factor in how such processes unfold. Managerialism at universities is a global trend and one frequently lamented and condemned (See Keyan G Tomaselli (2021) Contemporary Campus Life. Transformation, Manic Managerialism and Academentia. Cape Town: HSRC Press). It has resulted in the academic voice being devalued, job security undermined and remuneration imbalance (where some managers are paid much more than academics). Around the world, academic strikes are becoming more common.

At UCT, management has been under the spotlight.

Read: UCT to launch probe into conduct of vice-chancellor and chairperson after gruelling council meeting.

While the spread of managerialism is itself a concern for academics, the move towards authoritarianism among managers is particularly worrying (J Seekings and N Nattrass, “Resisting the rise of anti-democratic authoritarian managerialism at the University of Cape Town”).

The danger of these developments is that the status of a professor is undermined. If there is a suspicion that a person is promoted on grounds other than achievement through a transparent meritocratic process, the whole system of scholarship is jeopardised.

So how does one ensure transformation without going the easy route offered by a technicist approach, or by creating ideologically-loaded criteria and using authoritarian means to drive these through?

Building trust

An answer is to build a cohort of scholars who trust one another, who support one another and who celebrate one another’s achievements. The approach works with individuals but in a collective way. Members of the cohort are given opportunities to attend writing retreats, receive coaching and have regular one-on-one mentoring sessions. The result is increased productivity, confidence and achievement are ultimately promotion to the professoriate.

This is the approach used at UCT’s Next Generation Professoriate (NGP).

In 2015 a cohort of 35 black and female senior lecturers and associate professors were selected by their faculties. Over time the number increased to 45. By the end of 2022, 38 (84%) members had been promoted, 8 to full professor and 30 to associate professor.

At the outset, many were uncomfortable with being selected, worried about being identified as a deficit academic and not wanting to receive any special treatment. More than anything else, none wanted to become ‘development professors’ — promoted because of race or gender considerations rather than on the basis of their own hard work.

After seven years, the group had coalesced to become a strong support for each other. Many had been elected to Senate or become Heads of Department. They have in fact, become the future academic leaders of UCT.

This was no easy quick-fix or technical solution. But its impact on institutional culture, on the composition of the professoriate and on collegiality were much more likely to stand the test of time. At a time when UCT was beset by troubles, many felt that the NGP was their safe place – the place where they belonged. DM/MC

Dr Robert Morrell writes in his personal capacity. He is a Senior Research Scholar in the Centre for Higher Education Development (Ched) at UCT. He worked previously at the University of Transkei (now Walter Sisulu University), the University of Durban-Westville, the University of Natal (now UKZN) and UCT.

This article draws on: Morrell, R., Patel, Z. and Jaga, A., 2022. “I found my people”: Academic development, transformation and the Next Generation Professoriate at UCT in the South African Journal of Higher Education, 36(6), pp.11-27.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.