INSURGENCY OP-ED

The conflict in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique – a five-year summary

In May 2020 Cabo Ligado Weekly was launched by ACLED in partnership with Zitamar News and Mediafax as a new conflict observatory monitoring political violence in Mozambique. The aim was to present concise reflections on the Cabo Delgado insurgency’s development to that point, and identify key issues to watch. ACLED had noted the increasing competency of the insurgents, the momentum that they had at the time, and their evolving relationship with the wider IS movement.

We also noted the poor combat effectiveness of the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) in the face of the still relatively inexperienced insurgent forces. We pointed to FDS abuses, and how these reflected the depth of their dysfunction and highlighted the absence of an overarching counterinsurgency strategy that engaged communities constructively.

The progress made by the insurgents in the two and a half years up to May 2020 had been considerable. Though concentrated in five districts in the north of the province, and along the coast, they had also probed as far south as Ancuabe and Metuge.

The authorities had by then lost control of much of the north of the province.

In March 2020, the Quissanga and Mocímboa da Praia district headquarters were briefly occupied. In April, Muidumbe headquarters was occupied, and the following month it was the turn of Macomia headquarters. This ability would reach its peak in August 2020, when the insurgents, after months of activity, asserted control over Mocímboa da Praia town, expelling government forces.

Mozambican soldiers patrol the streets of Palma in Cabo Delgado on 12 April 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Joao Relvas)

A similar attack on Palma town in March 2021 would finally precipitate significant international military support. This would change the shape of the conflict over the subsequent 18 months, significantly impacting the dynamics of the conflict, but arguably bringing it no nearer to a conclusion.

By late 2020, the conflict had also unquestionably internationalised on both sides of the conflict.

The Mozambican state had in 2019 contracted with the Wagner Group, and then the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) in 2020 in its efforts to deal with the growing internal threat. The rapid growth of the insurgency over the first three years placed considerable pressure on Mozambique to accept bilateral and multilateral support. This came from many quarters, including South Africa, the Southern African Development Community (SADC), former colonial power Portugal, the US, the UK and the European Union.

Passengers and cargo board a boat from a fishermen’s beach that has become one of the main arrival points for displaced persons fleeing armed violence raging in the province of Cabo Delgado, in the Paquitequete district of Pemba, northern Mozambique, on 21 July 2020. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Ricardo Franco)

IS had, since June 2019, included Mozambique in its self-styled Central Africa Province through its Central Media Bureau announcements. As we discuss below, this essentially recognised existing links with elements in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), and likely Burundi and Tanzania, that were further along in affiliation with IS.

In May 2020, we pointed to the possibility of splits within the insurgency, pointing to the examples from West Africa, as well as Somalia and the DRC, where IS affiliation was followed by factionalism and splits. In northern Mozambique this has not been the case, and despite limited insights into the movement’s organisational frame, a flat, collegial leadership structure has remained united and strategically focused over the past five years.

Deaths

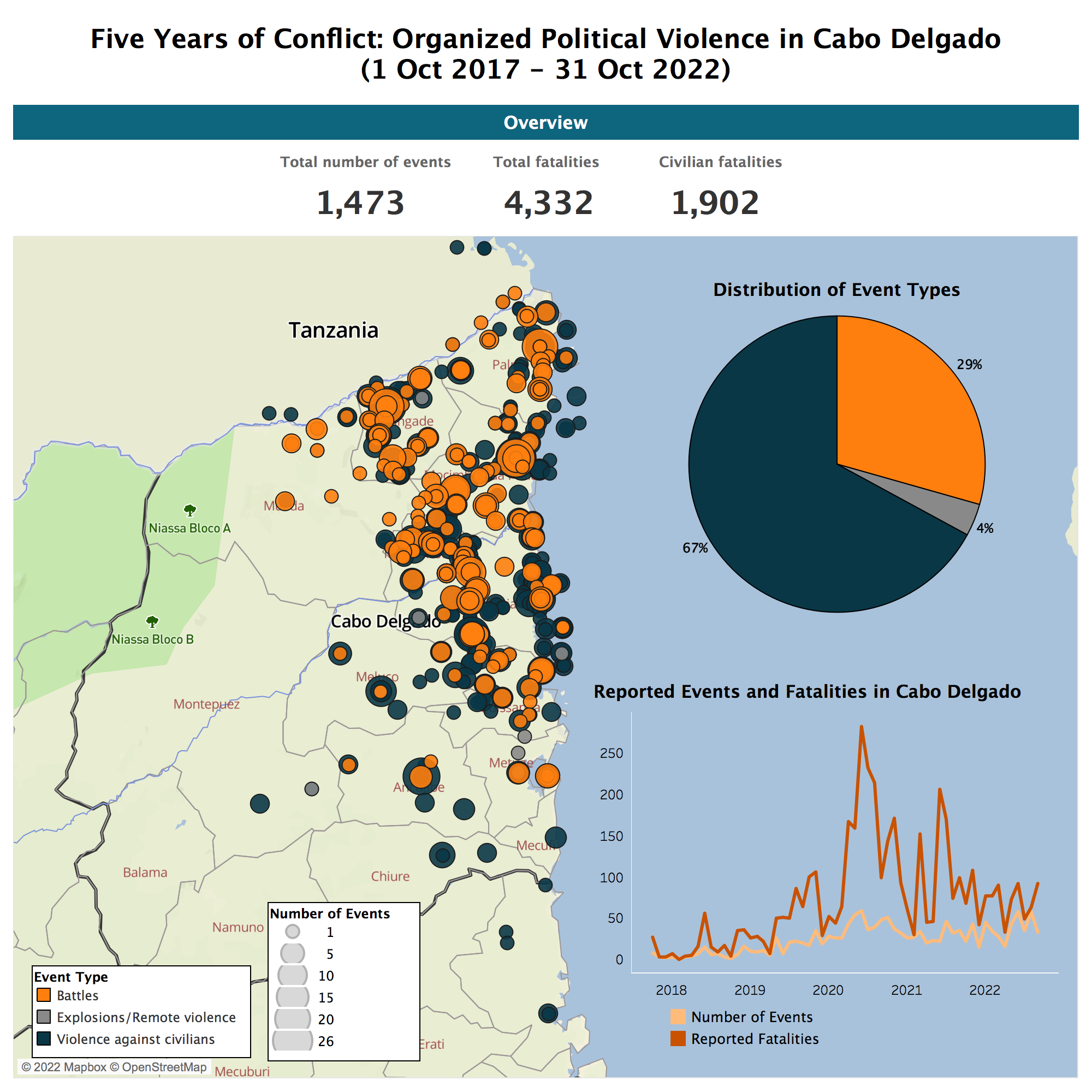

The conflict grew exponentially over this period, with deaths rising year upon year. The number of total reported fatalities was 204 in 2018, the conflict’s first full year. In 2019, this more than tripled to 619. In 2020, there were 1,720 reported deaths.

Within the data on fatalities, it is striking that the proportion of reported civilian deaths falls dramatically over the first three years, from 87% in 2018 to 47% in 2020. Though still alarmingly high, the rate of fatalities caused by the insurgents in the first three years increasingly approaches, if not matching, the rate of state forces’ fatalities. This likely reflects slowness in mobilisation and possibly the emergence of communal militias in the conflict’s first three years.

Read in Daily Maverick: “Mozambique’s deadly insurgency stems from minerals, natural gas discoveries — survey”

These grim data were also reflected in the growth in the number of insurgents. It was estimated by security sector sources that their number grew from just over 150 in 2017 to almost 3,000 by the end of 2020 when they first threatened the liquefied natural gas (LNG) plant itself at Palma. These numbers sustained significant military operations, supply chains with regional reach, and base support operations.

Residents try to return to normality in Palma, Cabo Delgado, on 12 April 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Joao Relvas)

Government losing control

By the second half of 2020, it was clear that Mozambique was losing control of the province, with sustained insurgent activity now in the districts of Nangade, Palma, Macomia, Quissanga, Ibo and Muidumbe, and isolated actions in Ancuabe, Pemba and Metuge in the south, and Mueda to the west. The security forces were facing serious allegations of human rights abuses, and in October even experienced a mutiny of sorts among the police’s Rapid Intervention Unit (UIR). Within the FDS there was friction between the Mozambican Police Force (PRM) and the Defense Armed Forces of Mozambique (FADM).

This would lead to control of the Northern Operational Theatre being wrested from the police and transferred to the FADM, first under Major-General Eugenio Mussa in January 2021, and two months later to his successor as chief of staff, Admiral Joaquim Mangrasse.

A woman and children in a shelter camp in Metuge on 16 August 2021. They are among many displaced people fleeing armed violence in northern Mozambique. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Luisa Nhantumbo)

The successful insurgent assault on Palma in March 2021, following an earlier New Year’s Eve attack on the LNG site next to the town itself, significantly shifted international interest in the conflict. By July 2021, troops from nine countries were deployed in the province. The SADC Mission in Mozambique (SAMIM) was deployed in August and was dominated by deployments from South Africa, Tanzania, Botswana and Lesotho. They arrived weeks after an initial deployment of 1,000 troops and police personnel from Rwanda under a separate bilateral agreement between Maputo and Kigali.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

These deployments came at the end of at least one year of diplomatic pressure on Mozambique to accept military support, especially from the SADC. Mozambique’s resistance to multilateral intervention, and perhaps under pressure to secure the LNG plant, resulted in this curious two-pronged arrangement. The relationship between the two forces went on to significantly shape the project.

Reported fatalities began to fall with intervention, but a worrying new pattern emerged with civilian casualties. The year 2021 saw reported deaths fall by more than one-third to 1,100, with more than a quarter of them being civilians. For 2022, the rate of reported fatalities has continued to fall – 644 to the end of October – but about half of these are civilians.

While primarily the responsibility of the insurgents, deployment and operational coordination may also be to blame for this. Rwandan deployments have for the most part secured Palma and Mocímboa da Praia districts, and allowed for the sacking of well-established bases that the insurgents had maintained along the Messalo river and in Mocímboa da Praia.

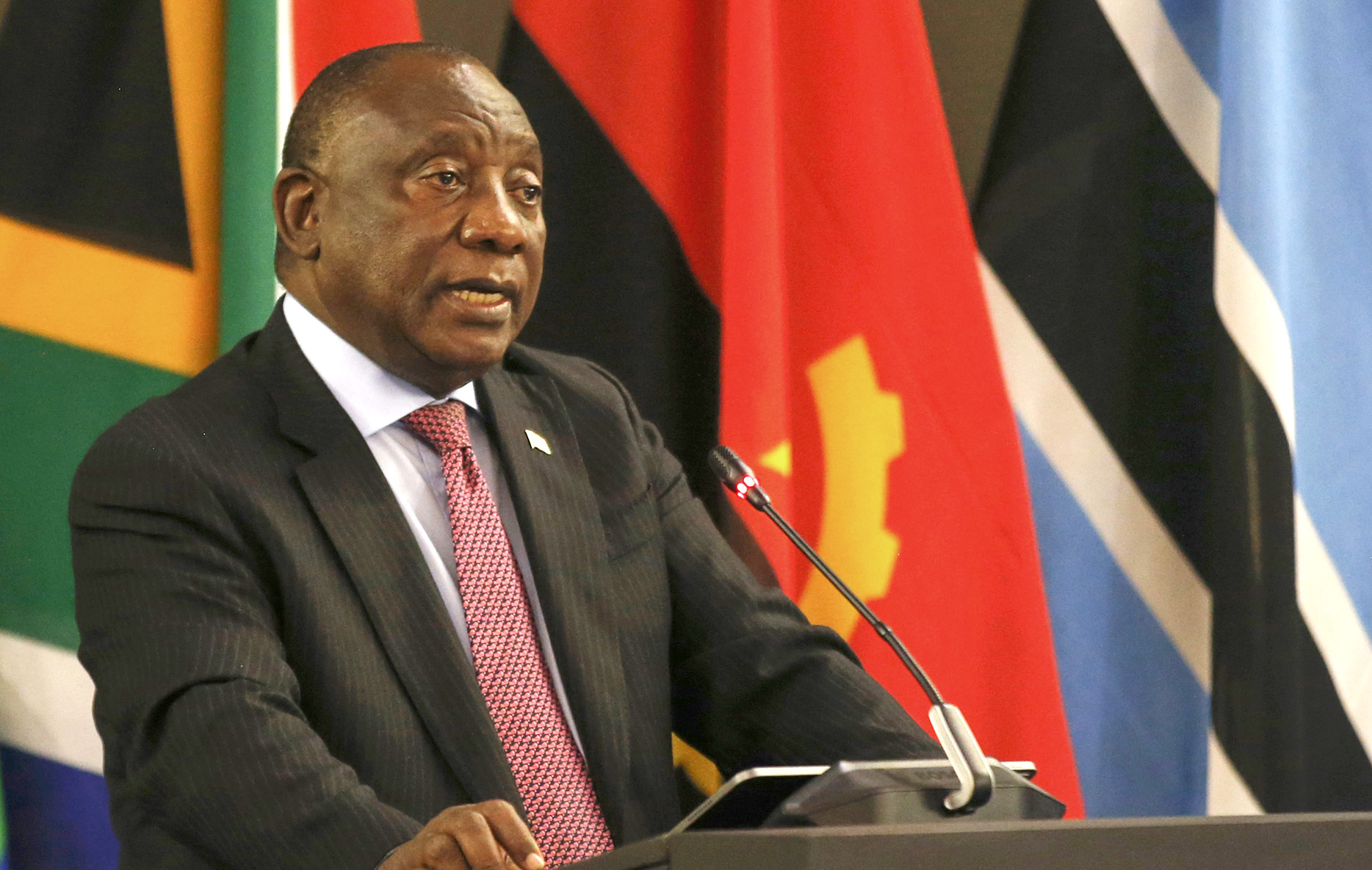

President Cyril Ramaphosa, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) chairperson on politics, defence and security cooperation, delivers the opening remarks during the Extraordinary Summit of the SADC Organ Troika Plus the Republic of Mozambique in Pretoria, on 5 October 2021. The summit received a progress report on the operations of the SADC Mission to Mozambique. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Phill Magakoe)

This has brought hard times to the insurgents. The defections, escapes and releases witnessed in January and March 2021 were testimony to how intervention forces disrupted supply chains and forced a dismantling of physical and administrative structures. By October 2021, security sources estimated that they had as few as 300 insurgents in the field, compared with 2,500 to 3,000 before July 2021.

This success has not been driven home. The insurgents’ response of breaking up into smaller dispersed groups away from the stronger intervention forces has been facilitated by the lack of backstopping operations when strongholds in places such as Mbau and Catupa forest were cleared. In the north, regrouping has taken place in weakly policed areas such as southern Muidumbe district or the marshy, forested land of Nangade. In the south, insurgents opened a new theatre covering Ancuabe and Chiure districts, and reaching into Nampula province. Operations now extend to Namuno and Balama districts.

Civilians are once again the primary victims as insurgents plunder to survive. DM/MC

Peter Bofin is a security analyst for ACLED on the Cabo Ligado project. He has worked on political risk, security and the oil and gas industry in East Africa for more than 10 years. Cabo Ligado – or “connected cape” – is a conflict observatory established by ACLED, Zitamar News and MediaFax to monitor political violence in Mozambique. The project supports real-time data collection on the insurgency in the country’s northern Cabo Delgado province and provides cutting-edge analysis of the latest conflict trends.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.