WORKING AGREEMENTS

Cooling of labour militancy in SA’s mines mirrors decline of migrant labour system

SA’s mining sector long benefited from the migrant labour system, and now it is cashing in on its decline — a decline that it has orchestrated.

When police shot dead 34 striking miners at Marikana in 2012, one of the widely cited factors behind surging worker militancy in the platinum shafts was the migrant labour system that long supplied South Africa’s mining industry with a rural, uneducated workforce that it subjected to brutal exploitation.

A decade later, virtually all of South Africa’s platinum group metals (PGMs) production — accounting for about 70% of the global total — is securely linked to five-year wage agreements. All were signed this past year without a tool being downed.

Workers at a sheep-shearing shed in Lady Frere, Eastern Cape. Mining company Sibanye Stillwater’s projects, which include helping emerging wool farmers, are linked to the company’s ‘Marikana Renewal’ programme. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

What explains this striking contrast, especially against the backdrop of a cost-of-living crisis that should be a catalyst for wage demands?

One possible factor is the dramatic decline of the migrant labour system, which has unleashed seismic social and economic shocks on other fronts.

Read more in Daily Maverick: “How the twilight of SA’s migrant labour system spawned a social apocalypse”

South Africa’s mines once employed almost 500,000 foreign workers, a number that now stands at 35,000. And it almost certainly employs fewer men now from other “labour-sending areas”, such as the former Transkei, than it did in the past.

Why would this trend pour cold water on labour stridency?

“Under the migrant labour system, the mineworkers were often supporting two households, an urban one near the mine and a rural household. And if there is a shift away from that, the economic demands on individual miners are decreased,” said Duncan Money, a mining historian at Leiden University in the Netherlands.

Maria Njengele is on the school governing board of a new school in Dutywa in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

Money was quick to point out that this was speculation on his part — and there is a dearth of data on this score — but it makes sense. Many a migrant mineworker in South Africa has had two households to support, and the system’s demise would presumably alter such relationships.

It is often said by unions and other observers that a typical mineworker has eight to 10 dependants. In 2016, the Minerals Council SA — the main industry body — estimated that the sector’s almost 460,000 direct jobs supported about 4.5 million dependants.

But there are no hard studies or recent surveys on the matter. On the one hand, if there are fewer mineworkers with two households to support, it simply makes sense that they would have less of a support burden.

Learners at Vulingcobo Junior Secondary School sit near the old pit latrine toilet in Xhora, near Elliotdale, in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

On the other, rising unemployment and poverty in South Africa’s disfigured and slow-growth economy have surely added to the numbers of people mineworkers — and many other wage earners for that matter — support. There is also an ongoing cost-of-living crisis in the face of high inflation, driven by food and fuel prices that take their greatest toll on lower-income households.

Moving away from questions of household dependency and incomes, it is important to note that a key union demand in the past was for the migrant labour system to be brought to an end.

In 1993, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) pressed the ANC — when it was on the cusp of power — “to adopt measures that will end the migrant labour system”, according to the late historian of the NUM, VL Allen. Grievances included the exploitation that migrants were subjected to and the hostel system designed to control this workforce.

The hostel system, at least in its old and coercive guise, is now largely a thing of the past — removing a key source of tension that was linked to the system of migrant labour.

Mechanisation

On top of that, the mining workforce has gradually become more skilled because of trends such as mechanisation. Even in conventional mines, tasks and equipment have become increasingly sophisticated.

Employees at operations such as Gold Fields’ mechanised South Deep mine now require a matric as a minimum level of education. These trends have meant, quite bluntly, that the mining sector is no longer served by semi-literate subsistence farmers drawn from rural areas where the quality of primary and secondary education remains woeful, to say the least.

This in turn helps explain the growth in real wages in the mining sector — albeit from a low base — during the past couple of decades.

Old toilets at JS Skenjana school in Dutywa in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

Minerals Council data on the annual remuneration paid to South African miners shows it rose each year on average by 9.4% from 2001 to 2020, according to Business Maverick calculations. South Africa’s Consumer Price Index, by contrast, averaged around 5.5% per year over that period, calculations made from Stats SA’s historical data show.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

So, wage growth in the mining sector almost doubled the rate of inflation between 2001 and 2020. In 2001, the average earnings per employee per year stood at R59,874. By 2020, that had reached R335,096, a five-and-a-half-fold increase.

That in turn helps to explain why labour assertiveness has become so muted.

The tragic events around Marikana a decade ago have played a significant role in these developments — I have described it before as a “Mechanisation Moment”.

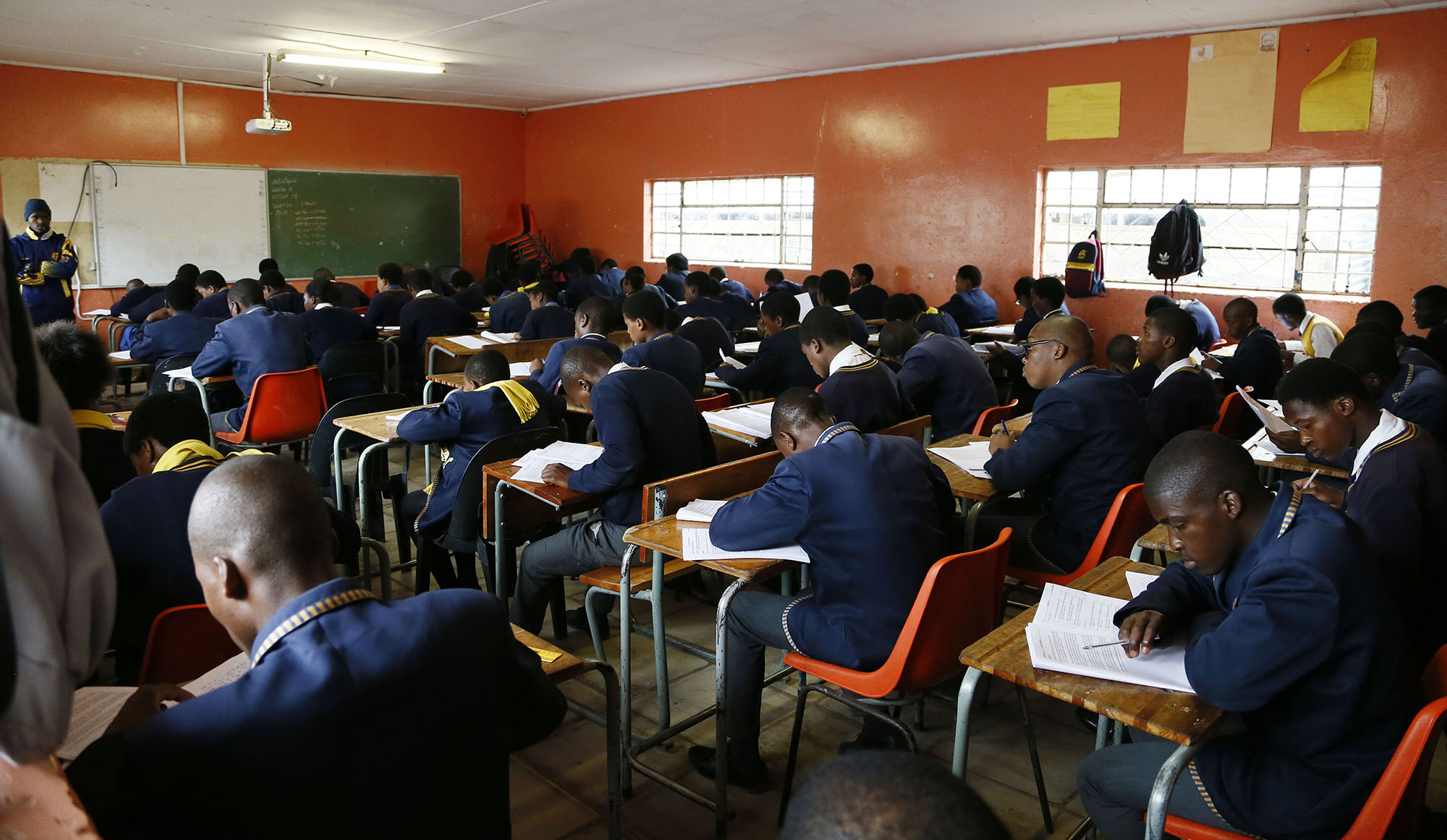

Learners write exams at JS Skenjana school in Dutywa in the Eastern Cape. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

Crucially, Marikana accelerated a drive to mechanisation, a key reason why the labour force today is smaller, better paid, and working in safer conditions. For some investors, South Africa’s labour-intensive operations effectively became radioactive in the wake of Marikana. Putting a lid on social and labour ructions became a high priority.

And as the roots of the turbulence were detected in the migrant labour system — migrant in this rendering meaning not from the local communities but places such as the former Transkei as well as neighbouring countries such as Lesotho — the mining industry also moved to reduce its reliance on these “labour-sending areas”.

Amcu and NUM

The initial wave of violence unleashed in 2012 as the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu) dislodged NUM as the dominant union on the Platinum Belt was triggered by rock drill operators who mostly hailed from the old Transkei.

A school governing board member, Mkhuseli Gqalelo, during the construction of new school toilets by Sibanye Stillwater, in Libode, Eastern Cape. (Photo: Felix Dlanglamandla)

A decade later, NUM and Amcu have buried their once lethal enmity under the banner of “Numco”. They have united in a number of wage talks — with Harmony Gold and other unions last year for a three-year deal, and across the platinum industry this year.

The two unions also went on strike together for more than three months earlier this year at Sibanye-Stillwater’s gold operations. Some commentators might say this points to lingering labour combativeness, but that would miss the point that much of this energy over the past decade was spent in a vicious union turf war. The most striking thing about the strike was its lack of violence — a state of affairs explained by the NUM and Amcu ceasefire.

For the industry and its investors — indeed, most stakeholders — this is a win-win. It has significantly reduced a key risk factor to investment in South Africa’s mining sector and allowed the platinum industry to seal stability with five-year wage agreements.

The mining sector long benefited from the migrant labour system, and now it is cashing in on its decline — a decline it has orchestrated. The stakeholders left in the lurch — whose emerging role in violent and illicit commodity trade networks is covered here — are the growing underclass of unemployed men spawned by these currents. The former labour-sending areas have also undergone economic trauma and shocks.

Labour militancy has been doused, but violent criminal activity and social discord have risen from the ashes. DM/BM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

While our mining industry is tainted by politics, we should not forget that most mining, indeed most finite life undertakings were and remain dependent on ‘migrant labour’. Mine’s often have to get up and running quickly, and even some listed operations have operating lives of less than 5 years. And so skills chase the jobs, it is just not feasible to provide full township services and a ‘fly-in-fly-out’ system is set up. It is a pity that our was not set up that way, because the services provided by most of these operations was considerably better than the people are currently getting from government. Contractors in construction work like this all of the time, but without services being provided to them.