BOOK EXCERPT

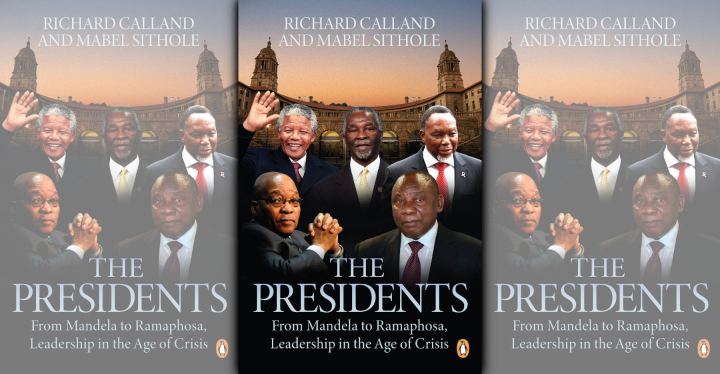

The Presidents: From Mandela to Ramaphosa, Leadership in the Age of Crisis by Richard Calland and Mabel Sithole

Since 1994, South Africa has had five presidents who have varied greatly in style and character, despite all belonging to the same political party. How do they compare? How did they handle the crises they faced? What impact did they have on the country?

Written with insight and rigour, and drawing from interviews with political insiders who are close to events, The Presidents: From Mandela to Ramaphosa, Leadership in the Age of Crisis shines new light on the leaders who have been entrusted with South Africa’s future.

As the ANC’s next elective conference approaches and Cyril Ramaphosa seeks a second term as president, South Africa is reeling from the effects of state capture and the Covid-19 pandemic. Coupled with an ailing economy and record unemployment, the need for good political leadership to steer us through the morass is more urgent than ever.

It’s the perfect time to think critically about the role that presidential leadership plays in our lives and in history. The Presidents provides an honest assessment of the five post-apartheid presidents – Mandela, Mbeki, Motlanthe, Zuma and Ramaphosa – examining their strongest qualities and greatest weaknesses in the context of the momentous challenges they faced. Read the excerpt.

***

Having finally become president, the question was whether Ramaphosa would be able to use his hard-won power. This is a perennial question for all politicians. The pursuit of power is their natural, and appropriate, instinct. Then the focus shifts to the surrounding context, with its many layers, as well as to the character and capability of the individual leader.

Zuma’s presidency created the mother of all crises – institutional degradation and endemic corruption, economic decline, and a crisis in political leadership that mirrored Brazil, where Lula’s presidency had led to an extreme economic downturn and negative growth of – 5 per cent. South Africa was headed in that direction but had somehow pulled back from the precipice. The rule of law had held the line and the ANC had – by a tight margin – chosen a reformer as leader. There was an opportunity to get back on track, but it would hinge on Ramaphosa’s ability to deliver the necessary presidential leadership.

Ramaphosa’s political and governmental inheritance was inconvenient, to say the least: a looted state, captured, hollowed out and, in many cases, institutionally broken. In addition, for the first time under ANC rule, the country was heading towards a fiscal crisis, again of Zuma’s making. As we showed regarding his attitude to the nuclear deal, fiscal probity was not top of Zuma’s priorities in government. His finance ministers, at least until the final year when Malusi Gigaba was appointed, maintained a measure of fiscal rectitude despite, rather than because of, their president. They were assisted by the institutional capability of National Treasury, which also came under attack, but which survived thanks to the courage first of Nhlanhla Nene and then Pravin Gordhan, as well as senior Treasury officials.

Yet even in this respect, Zuma made things worse on the eve of Ramaphosa’s victory at Nasrec. On the first day of the elective conference in December 2017, Zuma held a press conference at which he unilaterally announced that tertiary education would be free for students under a certain income threshold. There was no consultation with Treasury; even Zuma’s ally, then finance minister Gigaba, was caught off-guard and was visibly embarrassed when reporters asked him about the commitment made by the president. There had been no costing of the policy, no due process, just a reckless public promise – a classic piece of populism. The Ramaphosa camp was wrong-footed by the announcement, which was no doubt Zuma’s intention. They could not be seen to reject it, for fear of losing precious votes that had yet to be cast by ANC delegates in the ballots for president, the top six and the NEC. So, they went along with it. Ramaphosa was stuck with the policy, despite the further pressure it put on an already beleaguered fiscus.

The change which South Africans demanded required the new president to take a firm stance on corruption and maladministration, while addressing the nation’s economic downturn. According to Statistics South Africa, the economy had shrunk by 0.7 per cent in the year leading up to Ramaphosa’s presidency, signalling another recession after the 2008 global financial crisis. This recession was caused by a drop in the agriculture, transport, trade and manufacturing industries. In addition, a decrease in public service employment numbers had led to a 0.5 per cent slump in government activities.

Ramaphosa’s task was to arrest the decline and then to set the country on a different, positive course. Like a new CEO taking over a troubled, financially stricken company, he had to reverse things, to restore order, stability and prosperity. That was his mission; that was his mandate.

Then, just over two years after his first, dramatic and resounding State of the Nation Address, and as he was still building the platform for his administration’s attempt at economic and institutional renewal, the world was hit by Covid-19, the biggest pandemic in a century. Seemingly overnight, Ramaphosa’s job became even more difficult. But he was not alone in this, at least. Across the globe, presidents and prime ministers were waking up to face a challenge they could never have imagined.

At a time of grave national crisis, the most important first step for any leader is to inspire confidence, and the best way to do that is to be clear in the messaging while conveying the impression that government is responding quickly and capably. This Ramaphosa did when faced with the Covid-19 pandemic. His first televised address to the nation, delivered on the evening of 15 March 2020, was almost word-perfect. The twenty-nine-minute speech – lengthy, but justified at that moment, when people were craving information and guidance from their president – set the right tone: it gave a sense of the gravity of the situation, and there were clearly expressed announcements about what measures would be taken immediately and why. There was also a sense of hope. ‘This pandemic shall pass,’ Ramaphosa told his audience, before invoking the spirit of his inaugural SONA: ‘This is the most definitive thuma mina moment for our country.’

Ramaphosa rose to the occasion. And his decision-making did two things at once: it not only established a rapid institutional response, with the declaration of a national state of disaster and the special legal powers that came with such a step, but also bought time – a precious commodity during that early phase of the pandemic as it spread rapidly across the globe. With hindsight, many have heavily criticised the severity of the lockdown in South Africa that followed. By global standards, it was relatively harsh. And it was certainly long. Just how much time it bought, and how many lives were saved, is impossible to calculate. And it is far from clear that public healthcare services were able to take advantage of the flattening of the (infection) curve to build capacity.

Nevertheless, Ramaphosa’s response was credited with slowing infection rates and building on South Africa’s previous experience with pandemics in the first six months of the crisis. At the time, the Center for Strategic and International Studies noted:

South Africa’s response to the Covid-19 outbreak has been a standout in the region. President Cyril Ramaphosa has been an effective communicator, speaking frankly to his constituents about challenges ahead. His government moved to close borders and restrict movement and now is gradually adjusting alert levels and policies to ease enforcements in specific cities and communities. Leveraging its experience with HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, it has deployed mobile testing units and plans to produce 10,000 ventilators. In its earliest stages, the lockdown slowed down the rate of infections – around a 3 percent daily increase – but not without its costs.

In some respects, the pandemic brought out the best in Ramaphosa, especially in the first few months. In assessing presidential leadership, it is not only important to recognise the contours of the particular context, in order to be both fair and reasonable – as we have repeatedly argued in this book – but also to be careful not to apply the 20/20 vision of hindsight. We must assess the quality of decision-making against what was known at the time. In March 2020, a lot was unknown. The pandemic was scary. The right approach was surely to be cautious, to prepare for the worst. And here was an issue on which his political opponents could have no say – at least until corruption relating to government procurement of personal protective equipment (PPE) emerged, which triggered from the president a rare burst of genuine anger and disgust.

With hindsight, it might appear that Ramaphosa got the balance between lives and livelihoods wrong. This was the same difficult choice that was facing heads of government across the world. Ramaphosa and the members of the structure he quickly created to coordinate government action – the National Coronavirus Command Council (NCCC) – were deeply, and not unreasonably, concerned that Covid-19 might spread like wildfire through the working-class townships of South Africa, due to the density of dwellings, lack of access to basic healthcare, and in many places, inadequate sanitation. They were acutely aware of the weaknesses of the public healthcare system – which is why the NCCC repeatedly restricted alcohol sales, ostensibly to alleviate the pressure on public hospitals caused by alcohol-related injuries, such as car accidents and shebeen-related violence.

At a time of crisis such as a pandemic, the public has high expectations of a president. He or she is expected to step up and be more decisive. As Covid-19 caused mayhem in many countries around the world, there was every reason to act decisively. So, while it is true that Ramaphosa delegated authority substantially to key members of his cabinet, he was also emboldened by the pandemic, which in the public’s mind gave him more authority and power. Thus, it provided an illuminating window on what a bolder, more decisive and less politically exposed President Ramaphosa, unshackled by ANC factionalism, might look like, even though he could not prevent opportunistic theft: the Special Investigating Unit (SIU) later found numerous instances of corruption related to the Covid-19 pandemic, especially around PPE procurement. The findings were presented in December 2021 to SCOPA, which recommended that Ramaphosa take action against former health minister Dr Zweli Mkhize, who had been allowed to resign that August after being implicated in allegations of irregularly awarding a multimillion-rand communications contract to Digital Vibes, a company operated by two of his former aides. When news of the scandal first broke in May, Ramaphosa had dithered. There was ample evidence to at least suspend Mkhize. Even when an SIU report landed on the president’s desk with clear findings against the health minister that he and his family had benefited to the tune of almost R4 million from public tenders awarded to Digital Vibes, it took Ramaphosa another seven days before he required Mkhize’s resignation. And even then, he meekly allowed the disgraced outgoing cabinet minister to dictate the terms of his departure. Ramaphosa’s reputation suffered. DM/ ML

The Presidents by Richard Calland and Mabel Sithole is published by Penguin Random House (R300). Visit The Reading List for South African book news, daily – including excerpts!

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.