MATTERS OF OBSESSION

Reimagining Picasso’s Guernica

The story goes that a Gestapo officer shoved his way into Picasso’s apartment in occupied Paris and, pointing to a photo of the painting ‘Guernica’, asked: ‘Did you do that?’ To which Picasso replied: ‘No, you did.’

It’s so easy to draw a curtain – figuratively or literally – on the uncomfortable, the conscience pricking if you are in a position of power. But it’s impossible on both counts if you are on the receiving end.

Eighteen years ago, on the eve of America’s invasion of Iraq, the then US Secretary of State Colin Powell presented a case for war to the UN council. An invasion driven by an allegation – later proven unfounded – that Saddam Hussein had stockpiled liquid anthrax.

Since its donation by Nelson A Rockefeller in 1985, a tapestry reproduction of Guernica woven at the atelier of French artist Jacqueline de la Baume Dürrbach (with Picasso’s blessing) has hung outside the Security Council chamber at UN headquarters, as a perpetual reminder of the need for world peace. For Powell’s presentation workers placed a curtain of UN blue obscuring the antiwar tapestry along with flags of the council’s member countries. The irony blazes even from behind the drawn curtain. The official reason for the cover-up was that a blue background created a more effective backdrop for the television cameras. But art critic Peter Goddard was closer to the bone when speculating that the cover-up was the UN’s realisation that images of the tapestry’s anti-war directive would be televised globally when it appeared as a backdrop to the interim report by chief weapons inspector Hans Blix.

But for the villagers referenced in the Guernica tapestry or those Iraqi civilians on the receiving end of war there was no curtain to draw. The destruction had such a powerful impact on one survivor that when faced with the carnage he lost consciousness.

A member of the security detail for John Bolton, the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, speaks on his radio in front of a reproduction of the Pablo Picasso painting Guernica, 12 May 2006, at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Image: Chris Hondros / Getty Images

British Marxist Raphael Samuel wrote: “It is rather a social form of knowledge, the work, in any given instance of different hands.” His quote refers to history but it could just as easily apply to the “remakings”, reconstitutions and reiterations of famous historical paintings, in particular Picasso’s Guernica.

‘Guernica’ by Pablo Picasso at the Reina Sofia Museum on 3 June 2020, in Madrid, Spain. Image: Carlos Alvarez / Getty Images

The painting references a two-hour strafing – a new military tactic – by German and Italian air forces of the ancient Basque town of Gernika, on the weekly market day in 1937, at the time of Spanish Civil War. Gernika in northern Spain was the centre of Basque cultural tradition. The bombing is considered the first complete destruction of a civilian target from the air – although some have suggested it was a bridge they wanted to hit but unfamiliar with the new method of strafing they weren’t successful. At the Nuremberg war crimes trials Hermann Göring acknowledged that Gernika was a practice site for the Nazi air force to sharpen their fighting strategies and skills.

All the villages around the town were also bombed. The bombing was at the request of the Spanish Nationalists under the command of the fascist General Francisco Franco who would go on to rule Spain after the Spanish Civil War. Gernika had no strategic value as a military target and yet ironically the factory producing war material outside the town and a bridge were both spared. Franco denied bombing Gernika; however, a secret report subsequently revealed that the objective in bombing the town was to break the Basque resistance to Nationalist forces.

Seventy percent of the town was destroyed and a third of the population (1,600 civilians) were either killed or wounded. As Lael Wertenbaker, author of The World of Picasso, wrote: “Never before in modern warfare had noncombatants been slaughtered in such numbers, and by such means.”

Picasso read of the bombing in the newspaper while in Paris where he was working on a painting commissioned by the Spanish Republican government. A month later, in response to the news, he began working on a new 3.5m-tall by almost 2m-wide painting titled Guernica. Interestingly, it started off as a colour painting, its stark, monochromatic outcome a direct influence of the black-and-white photographs that recorded the painting’s development. A pull-back from the drama of the “red of blood and fire” in the matt finish of ordinary house paint.

This painting, considered the most powerful antiwar statement in modern art, was first exhibited at the Spanish pavilion at the World’s Fair in Paris in 1937. Its brief global tour helped draw attention to the Spanish Civil War. Activism was not Picasso’s nor fellow artist Salvador Dali’s primary drive. However, each artist produced one painting that could be placed in this category. Picasso’s Guernica and Dali’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War). Yet Guernica, like Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, Goya’s Third of May and Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass has been remade, reimagined, reiterated, appropriated and reconstituted by hundreds of artists, whether as spoofs or serious, like a dark “gift that keeps on giving”. Picasso himself reimagined Goya’s Third of May and Velázquez’s Las Meninas.

It’s also curious that many reimaginings are mash-ups of Guernica and The Raft of the Medusa. Take Jovcho Savov’s Guernica 2015 and Greek cartoonist Giannis Kalaitzis’s Guernica, which both reference the refugee crisis and war.

While politicians bury their heads in the sand, artists point at the real issues. Jovcho Savov’s “Guernica 2015” pic.twitter.com/zfu5sfgZTI

— MSF International (@MSF) February 6, 2016

The vote for the most prolific reimaginings goes to American artist Ron English for his 100 Guernica’s and their wide-ranging applications from Snoopy vs Simpsons Guernica to Fat Food Guernica.

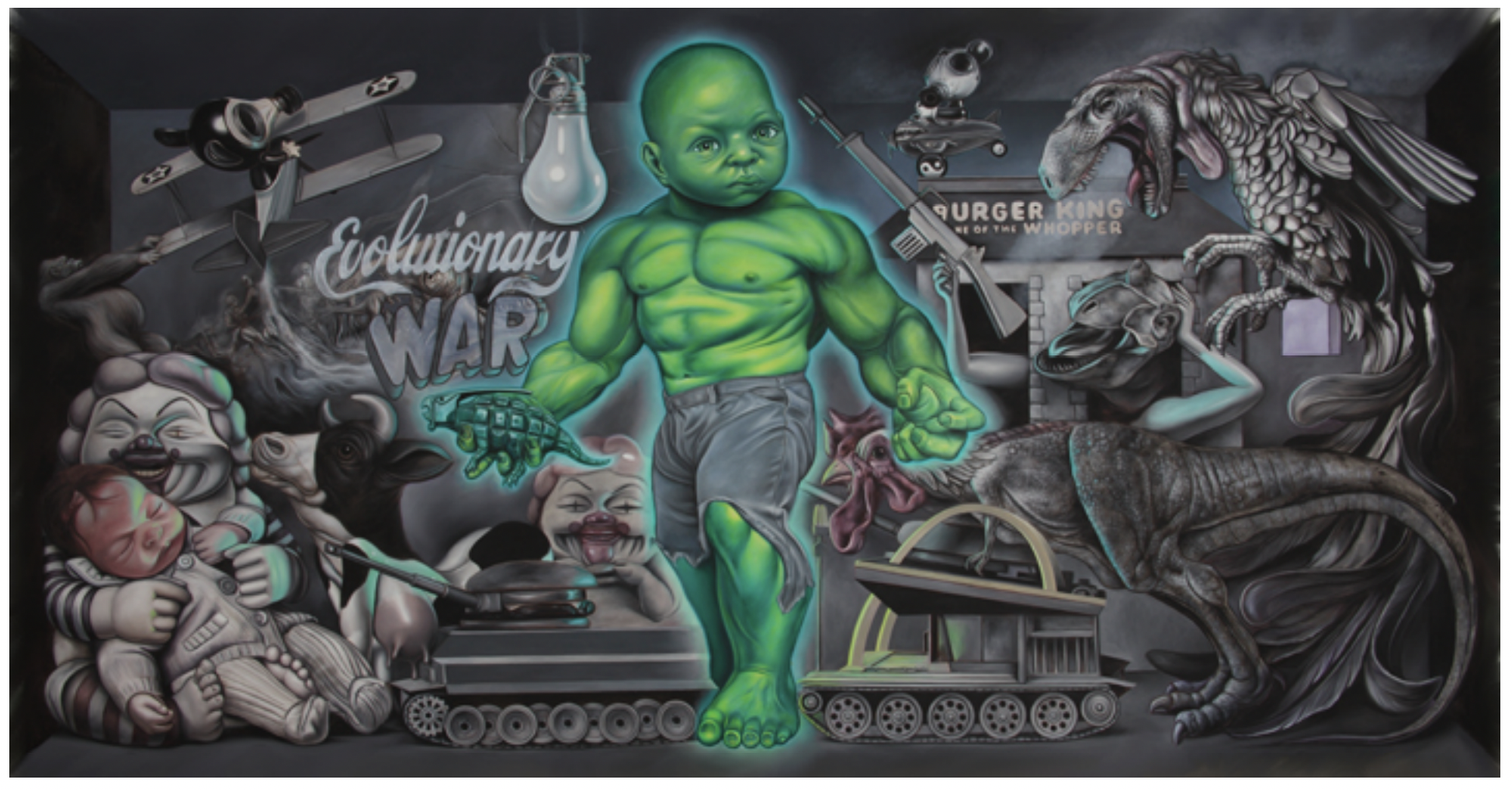

English uses Guernica as a template or a point of departure to comment on “global corporate culture” and “war as entertainment and entertainment as war” with a Pop Surrealist treatment. English has a curious approach to the original Guernica, believing that Picasso’s approach “transforms incomprehensible tragedy into a cartoon narrative”.

‘Mythological Guernica’ 2015-2016 by Ron English. Image: Allouche Gallery

‘Evolutionary War Guernica’ 2014-2016 by Ron English. Image: Allouche Gallery

Other iterations are Lena Gieseke’s 3D exploration of Guernica, a pixelated Lego Guernica, Robert Longo’s charcoal drawing Untitled (Guernica Redacted, Picasso’s Guernica, 1937) 2014 in which the artist has imposed thick black bars as if to suggest the juddery newsreels of the past or prison bars, Dupuy-Spencer’s Veterans Day (2016) painting where the original Guernica features as a small printed reproduction on a sunny yellow bedroom wall next to a small photograph of American brigadiers who volunteered to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

Some of the most successful reimaginings are those created in fabric and often collaboratively. There’s Sul filo dell’arte which produced elements from the original painting in 3D knitted forms.

And a protest banner titled The Remaking Picasso’s Guernica (2012-2014) to be carried on protest marches. Created by a Brighton-based activist collective including academic Dr Nicola Ashmore who has written and made films on some of the remakings of Guernica. The aim of the banner was to “draw attention to historic and current government-led aerial attacks on civilian populations”.

Two of the most successful imaginings of Picasso’s Guernica are either made from fabric or incorporate fabric and they both involve collaboration: Goshka Macuga’s installation The Nature of the Beast and the five Guernica tapestries by the Keiskamma Art Project. Both use the painting as a springboard to comment on devastation and war. The devastation of war as in the case of Macuga and the pre-antiretroviral devastation of HIV/Aids in the case of the Keiskamma Art Project, particularly in rural South Africa.

Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ is displayed at the Whitechapel Gallery on 23 March 2009 in London, England, featured in ‘The Bloomberg Commission – Goshka Macuga’ a one-year installation by Goshka Macuga sponsored by Bloomberg in preparation for the gallery’s official reopening on 5 April 2009. Image: Dan Kitwood / Getty Images

Turner Prize-shortlisted artist Goshka Macuga stands with a tapestry of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ on display at the Whitechapel Gallery on 23 March 2009 in London, England. Image: Dan Kitwood / Getty Images

The Nature of the Beast was first exhibited at London’s Whitechapel Gallery in 2009. It comprised several elements with the focus on the Guernica tapestry and the recognition of its “ongoing power and extraordinary capacity to signify the suffering of many civilian populations: from the Spanish Civil War to the second Iraq invasion and beyond”. Other elements included the blue curtains placed behind the tapestry in the same shade that were used to cover up the tapestry referencing Colin Powell’s invasion speech, a black and red war carpet leading up to the tapestry, a round, glass-topped table, suggestive of the assembly room in the UN Security Council, displaying archival material and a bronze statue of Powell delivering his speech.

One can understand why Pulitzer Prize winner for criticism and senior art critic and columnist for New York Magazine, Jerry Saltz, regards the Keiskamma Art Project tapestry Guernica (2010) as one of the most successful reimaginings. Currently on display at Constitution Hill in Johannesburg until 24 March 2023, together with the many other tapestries it forms part of the exhibition Umaf’ evuka, nje ngenyanga / Dying and Rising as the Moon Does, celebrating the Keiskamma Art Project’s 20th anniversary.

***

The Keiskamma Art Project is known for reworking iconic Western artworks around the themes of despair and hope. They include the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry which narrates our country’s history and the post-democratic elections disappointment, the Keiskamma Altarpiece commemorates the lives of those who died of HIV/Aids inspired by Matthias Grünewald’s 16th-century Isenheim Altarpiece and the Creation Altarpiece inspired by the Ghent Altarpiece.

The 2010 Guernica by the Keiskamma Art Projects is the first of five remakings of the painting and is the only one made to Picasso’s original scale. First exhibited in 2010 in a sacred indoor kraal, the tone is one of rage and under-the-rage deep despair of HIV/Aids in the form of Thabo Mbeki’s denialism of the disease and his government’s lack of medical support. The Keiskamma Guernica is not a slavish copy of Picasso’s, but a nuanced version rich in cultural interpretation, a dialogue between two different cultures with a shared humanity.

The 2010 Guernica by the Keiskamma Art Projects. Image: Keiskamma Art Projects

Workshops for the Guernica tapestry began with a social worker who got women embroiderers from Hamburg to draw their grief and suffering using Picasso’s weeping women series as a starting point. These, along with children’s drawings of weeping, appear on the background as fine white outlines, like tattoos of human suffering.

The shattered flatness of Picasso’s Guernica lends itself perfectly to a flat tapestry of embroidered cloth fragments. Made poignant once one understands that the incorporated striped, grey cloth fragments were once part of blankets that held the dying forms of HIV/Aids patients at Umtha Welanga, a hospice which Dr Carol Hofmeyr, the founder of the Keiskamma, started in an abandoned house in response to the desperate lack of facilities.

The Keiskamma Guernica tapestries are the only ones where Hofmeyr appears – her anguish howled to the sky, arms raised and her head thrown back – surrounded by the bodies of children and adults.

Embroider Nozeti Makhubalo stitched the Pieta composition of a mother with a skeletal child across her lap and Nokphiwa Gedza the women wearing traditional ibai and imibhaco clothing drawn from a photograph of women at a funeral.

Artist Thobisa Nkani created a version of what Picasso termed a “sick sun”, because it gave out no light, with wire, replacing the lamp for an electric bulb. This concept was first introduced by the large lamp featured in Goya’s Third of May, described as a black light because it illuminated the horror of a mass execution of Spanish civilians by the invading French army. The problem of finding the right yellow for the “sick sun” was solved when Nkani agreed to sell his pale yellow shorts.

Stitched to the hem of the tapestry are rows of tiny metal plates with R.I.P and the names and dates of those who died at the hospice in Hamburg. These refer to the metal markers that mark each grave before a permanent gravestone is erected. Hofmeyr happened to be driving past Motherwell, a municipal cemetery, when she witnessed the devastating sight of a sea of hundreds and hundreds of metal grave markers glinting as their backs caught the afternoon sun.

There is no consensus about the meaning of the bull and the horse in Picasso’s Guernica. Even Picasso wasn’t clear, vacillating between the bull symbolising “brutality and darkness” and his work not being symbolic. He suggested that it wasn’t “up to the painter to create symbols” but rather the job of the public and the viewer.

But in the Keiskamma Guernica the symbolism is clear.

The angry bull is the work of Cebo Mvubu known for his angry bovines which represent the lack of support from the denialist Mbeki government. The horse is replaced by a cow sacrificed to appease ancestors and ask for help. Embroider Nombuyiselo Malumbeso depicts the cow with a throat wound, its head thrown back in agony. Perhaps the most heart-rending of all in the piece and one which makes personal the agony of HIV/Aids in the time of Mbeki, is the writing embroidered on the cow’s body. Hofmeyr explained how it’s a record of four cellphone text messages, sent over 24 hours from a community health worker to Hofmeyr, asking for help for her dying brother when the ambulance did not arrive. The last message read: “He is dead.”

Then there are the ochre birds that fly over Hofmeyr’s head, symbols of the need to escape to another world coupled with hope. Always hope.

On the 50th anniversary of the end of World War 2, 27 years ago the Kids’ Guernica International Children’s Peace Mural Project was born – an initiative of a Japanese cultural organisation, ART JAPAN NET WORK. The idea was to foster a global peace consciousness using child-centred peace paintings created during workshops on canvases the same size as Picasso’s Guernica.

Savina Tarsitano, an Italian artist and activist, has been involved with Kids Guernica for 15 years across the globe and the making of what she calls “movable murals “for peace and solidarity”. Her collaboration with Ashmore and Guernica Remakings started in 2019. This year Kids Guernica, in partnership with the Keiskamma Art Project, visited Hamburg and Gqeberha where two new Kids Guernica canvases were created.

It may seem to be a dark painting for kids to work with, but through a series of workshops Kids Guernica encourages young people to draw from their own experiences and work collaboratively on the meaning of peace using visual images to express their feelings. The outcome, a movable canvas but more importantly the realisation for these young people that they are not alone in their experiences and struggles. And perhaps through their engagement in projects like these this new generation can lay the ground for global peace. For “hope is the thing with feathers”. DM/ML

In case you missed it, also read The Keiskamma Tapestry: How the hands of 100 women coaxed a visual account of South African history into life, stitch by stitch

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.