AFTER THE BELL

Game of cat and mouse — the future of the Free Market Foundation

After a bitter split and the departure of its champion Leon Louw, what does the future hold for the FMF? My guess is that almost nobody in the broader political establishment knows, or, to be honest, cares. But I don’t think free market ideas are anywhere near dead, least of all in South Africa.

I suspect most of South Africa’s political class looks at the Free Market Foundation (FMF) with a special kind of trepidation. There are — at least! — three reasons why this is the case.

First, South Africa’s culture is heavily dominated by left-wing thought, as many countries with a large proportion of poor people are. For the poor, the notion that somehow a free market is going to improve their lives seems distant and inchoate. But the idea that the government should help seems much more immediate, practical and meaningful.

The larger the middle class, the more ideas about rule of law and property rights resonate. But, you know, you have to actually own some property before the notion of property rights becomes really tangible.

Second, South Africa’s politics are dominated by the ANC, and the ANC itself has a long history of association with communism and socialism, as we all know. Of course, whether the party acts according to these principles is a matter of debate. But, at an ideological level, the volume of left-wing thought in South Africa is dominant to the point of being overpowering.

I’m often amazed at how South African academics consider themselves to be in the mould of international thought, but, in fact, they are much more left-wing than even they think they are.

I once had a long debate with a very prominent South African lawyer who supported a wealth tax and upbraided me for not paying more attention to the views of renowned people such as Martin Wolf, the economics editor of the Financial Times.

As it happens, I’ve followed Wolf with awe for years and I consider my own politics very akin to his. I was forced to point out that Wolf has written publicly that he flat-out opposes a wealth tax. The lawyer didn’t know.

And third, I think the notions that underpin the free market movement have internationally taken an enormous hit because of two things: the 2008 financial crisis, whose origins can be traced back to unregulated financial gizmos that smashed through the global economic wealthfare like an asteroid; and the Covid-19 crisis, which underpinned the need for an active and effective public healthcare system. (Not to mention the widening inequality attributed to the pandemic as the billionaires, clear beneficiaries of the free market, got richer while so many others fell through the net.)

Bitter split

For these reasons and others, the FMF has been swimming upstream for years. But this past year was a crisis moment for the organisation, particularly after it effectively ousted its founder and leading light Leon Louw in a bitter squabble that split the organisation.

Leon Louw. (Photo: Gallo Images / Lee Warren)

Given all the forces in South Africa that opposed Louw, what he did with the organisation was quite something, positioning it as a force for freedom for the poor. Street vendors and township homeowners were just two of the sectors where the organisation focused its attention. This was in stark contrast to the distinctly right-wing flavour of most free-market organisations.

Louw’s perseverance did have an impact on the political spectrum, but the big win was when former FMF executive member and self-made businessperson Herman Mashaba became mayor of Johannesburg.

One of Mashaba’s keynote efforts was to try to get freehold rights for township dwellers, a campaign that came right out of the FMF’s playbook.

So now, post-split, post-Louw, what happens to the FMF? My guess is that almost nobody in the broader political establishment knows, or, to be honest, really cares. Maybe it’s just my own predilections, but I don’t think free market ideas are anywhere near dead, least of all in South Africa.

The waiting game

The FMF has just appointed a new CEO, David Ansara, who worked at the Institute of Race Relations and its subjunct, the Centre for Risk Analysis.

I spent some time shooting the breeze with Ansara, and he is really interesting and entertaining, but I can tell you now, a lot of people are not going to like his views.

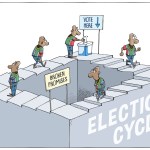

One of the things I asked Ansara was about the sheer weight of ideological opposition in South Africa to the ideas of the FMF, and he had an interesting answer: The point of free market ideas, which he calls “classical liberalism” partly to distinguish them from more extreme libertarianism, is that they need to be available when the time comes. It’s a waiting game. Cometh the hour, cometh the playbook.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

For example, he said the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), a free market think tank, existed for years in the UK and trundled along without anyone taking much notice of it. Then came the Winter of Discontent in 1978, with strikes everywhere and rubbish piling up in Leicester Square.

The result was the end of the Callaghan government and the advent of Thatcherism. Within a decade, huge industries were privatised, not only in the UK, but all over Europe, and they remain private today. The ideas of the IEA suddenly caught fire.

A similar set of events took place in China. For decades, the Chinese economy faltered under communism, until suddenly Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping declared that it didn’t matter what colour the cat was, so long as it caught the mice. But, by that stage, Chinese citizens were taking things into their own hands and far from dictating the change, the change was being dictated to Deng, Ansara points out.

The ‘compacting trap’

One of the issues between the factions of the foundation was the extent to which it should be part of South Africa’s social-compacting tradition, which older members had supported, partly because it provided some sort of access to the political system.

But given South Africa’s enduring economic malaise and growing corruption in government, the opponents of social compacting argued that a new approach was necessary. There were other issues too, but my guess is that this was the heart of the debate.

Ansara is distinctly in the new camp. There is no necessity to be divisive, he says, but adds: “I don’t think we are in the business of making friends. We are in the business of defending freedom.”

Too many organisations in South Africa have fallen into the “compacting trap” and the result has been a sclerotic economy, he says. Instead, Ansara argues in favour of a “transactional approach”. Business, for example, should recognise its bargaining power and broker agreements, rather than merely engage for engagement’s sake.

He describes broad-based black economic empowerment, for example, as an “elite enrichment scheme” that has become an obvious example of how government overreach creates more problems than it solves.

“It’s been a disaster for South Africa,” he says.

Affirmative action similarly gets short shrift: “It undermines black people’s agency to improve their own circumstances.”

In the meantime, the FMF is going to carry on with its Khaya Lam programme, getting township dwellers freehold rights to properties they have lived in for generations and it will work on its job seekers programme.

And, one presumes, it will wait for the moment when people start caring about whether the cat catches the mice as opposed to what colour it is. BM/DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I disagree with Ansara on two points. The first is Deng Xiaoping. It’s true that there was some spontaneous free market activity emerging in China at the time. People tend to forget that the CCP had totalitarian control. They could have crushed those emergent enterprises. Deng chose not to because it suited the CCP. He was not forced. He absolutely could dictate what did and did not happen. That is still true in China today.

The second is the point about not being in the business of making friends, but about being in the business of defending freedom. Nice soundbite, but absolutely meaningless in practice. Defending freedom is an inherently political activity. You achieve political goals by making “friends” – allies, if you will. Defending freedom requires the making of friends. If he thinks the two are mutually exclusive, I question his competence.

Great stuff thanks Tim. We need more people to recognize that BBEEE is fir the so-called elite to take what is not theirs