analysis

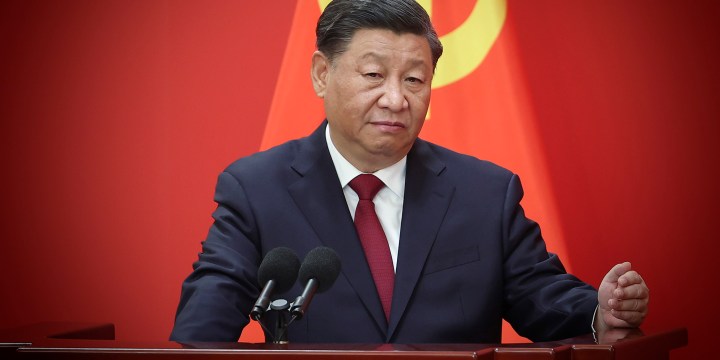

Mao Zedong 2.0: China’s Xi Jinping, now officially the new Great Helmsman

Xi Jinping, breaking with precedent, is now going to have a third five-year term as the leader of the world’s second-largest economy and global power. What does this mean for China and the rest of us?

Let us be clear about the political fortunes of China’s current leader, Xi Jinping, along with the rise and rise of his country in the contemporary world. Together, they can be seen as elements of the newest version of Chinese historical development over many centuries.

As part of that story, what has just happened this past week as he has claimed a historic third five-year term as communist party head (and thus, inevitably, the confirmation of his position as head of government and state) deserves a close look as well, even if there was absolutely no suspense associated with that result.

But first, a brief glance at history. History is not, of course, an inevitable guide to the future, but it always offers important clues about events and long-term trends.

Back in the 18th and early 19th centuries, Western traders wracked their collective brains to identify products that could be exchanged in the hongs (those foreigners’ entrepôt warehouses in Guangzhou) of China’s coastal city for China’s highly admired products. Like silk and finely woven cotton fabrics, highly desirable porcelains, tea, and a roster of other products were in demand by the growing consumer numbers of Europe and America.

By some admittedly sketchy estimates, China’s share of the global GDP may have been around 40% in the 17th century. Well before that period, China had been the key part of a sprawling trade network — the fabled “Silk Road.”

That network had tied the Middle Kingdom to Central Asia, the Middle East, and the people of the Roman, then Byzantine, Empire for two millennia. Those trade routes, in addition to commerce, also brought religious, artistic and cultural values and intellectual ideas across the great mass of Asia as well — even bringing the Greek notion of the contrapposto stance to cultures all along the Silk Road.

For millennia, China’s rulers had the power to marshal vast numbers of people and resources for the construction of massive public works projects, ranging from the famous Great Wall to vast canals and irrigation networks.

This pattern has been described by some scholars as the widespread phenomenon of oriental despotism as a way of organising human endeavour. (In the years following the communist revolution in 1949, a similar orientation has permitted equally massive, command economy-style public works projects. This has been especially true in the post-Cultural Revolution period, with the construction of vast new road and railroad networks, and entire new cities and manufacturing zones.)

Rather than overland, that wave of traders in the 18th and 19th centuries — coming by sea from Britain, the Netherlands, America, and elsewhere — after struggling with finding desirable product offerings to the Chinese, eventually identified the humble ginseng root — long famed in East Asia for its effects as a kind of early energy drink — as a leading item for sale to China, together with high quality beaver pelts, and, naturally, silver and gold bullion. But it is hard to build a great, modern commercial empire based on the root of something pretty close to being a weed or the pelts from a furry mammal.

Opium trade

However, by the 1830s, the British had found the magical item to establish an extraordinarily profitable trade with China, given the nearly inexhaustible demand for opium grown in India and then shipped to its users in China.

The obvious downside of this trade, besides opium’s baleful effects on its users and society writ large (a challenge the contemporary world is encountering yet again with both naturally grown opiates and even more potent, factory-produced alternatives), was that the Chinese government insisted opium was an illegal import because of the social ills associated with it.

This clash over principles and commerce led to Western conflicts with China, and its defeats further weakened Qing dynasty rule there. One side effect was a palpable sense among Chinese that the West was a predatory collection of barbarians eager to feast on the ruination of increasingly enfeebled China. The various wars and unequal treaties eventually led to ports forcibly opened to western commerce, as well as the ceding of Hong Kong to Britain and smaller ports to France, Russia and Germany, and a 900,000 square km expanse of territory in Northern China to imperial Russia.

This period, frequently referred to as “the century of humiliation,” remains a major trope in Chinese historical reckonings, and continues to crop up in speeches by the country’s leaders (both opportunistically when they are offering critiques of the West, or when used to express a widely held Chinese view of history). It also comes along when Chinese officialdom replies tit-for-tat to foreign critiques of Chinese domestic repression.

Communist victory

The communist victory of 1949 followed decades of internal strife and regional rule by warlord regimes, as well as the Japanese invasion after the collapse of the old imperial government in 1912. That revolution under Sun Yat Sen had been carried out to bring in a more democratic system, but the political and economic chaos in the nation largely doomed that government even before Japan’s invasion of the 1930s.

By the time the communist party’s forces had defeated the Kuomintang Nationalist government in 1949 (which then fled to the island of Taiwan, setting up the current issue), the new regime’s promise of providing stability and a new, fairer economic order guaranteed the acquiescence by, if not active support from, millions of peasants and city dwellers.

However, as well documented, during Mao Zhedong’s authoritarian rule, between 30 to 65 million people perished due to famines and calamitous economic policies. The upheavals of the Cultural Revolution caused a new wave of chaos and economic disaster for China.

Deng Xiaoping’s government and those of his successors returned a sense of stability and order to the nation as the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution receded. Deng’s government (and his successors) began supporting limited economic experimentation and allowing growing opportunities for private enterprise in controlled circumstances. This laid the foundation for China’s massive economic boom from around the beginning of the 21st century, especially after China fully engaged with the rest of the global economy and joined the World Trade Organisation — with the encouragement of Western nations.

Hundreds of foreign businesses and manufacturers quickly established their respective presences in China and formed partnerships with local Chinese businesses, turning the country into the globe’s newest version of a nation being dubbed the world’s workshop. This economic explosion created a new class of dollar millionaires and billionaires, fed the steep rise of China’s own consumer culture, and clearly lifted many millions of China’s poor out of their dire circumstances.

While economic experimentation was increasingly permitted in those heady days, the same cannot be said of increased political freedoms — as the brutal suppression of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations in 1989 clearly demonstrated, and then, later, there have been the continuing difficulties of the Uighur population and Hong Kong’s rally-goers pressing for democratic reforms in that former British colony.

One of the Chinese government officials who had been harshly treated during the Cultural Revolution had been Xi Jinping’s father, Xi Zhongxun, a stalwart of the communist party’s rise to power. After he was allowed to return to government positions following his political rehabilitation, one of his great successes had been the formation and development of the new economic zone of Shenzhen, located close to Hong Kong.

Shenzhen had been established in response to the attraction of and the better opportunities offered by Hong Kong to the population of Guangdong Province. Shenzhen’s extraordinary growth and new wealth from what had been a collection of small villages and farmland transformed into a massive conurbation of urban dwellers, factories, offices, and more, was seen by many as a model for the future of the “new China.”

Xi Jinping

Given that background, many observers predicted that as Xi Zhongxun’s son, Xi Jinping, rose to supreme power following his time in Fujian Province as governor and then in a position of power in the megacity of Shanghai, his father’s experimentation would carry over to the son’s thinking as well, once he took on China’s leadership in 2012. Moreover, Xi’s presumably positive experiences during time spent in the US were also thought to be an influence on and predictor of his future behaviour. But Xi apparently had different ideas.

As he rose in the communist party’s ranks, in 2007 he became one of the nine members of the standing committee of the CCP’s Political Bureau (Politburo), the highest ruling body in the party. That put him on the short list of likely successors to Hu Jintao, who had been general secretary of the party since 2002 and president of the People’s Republic since 2003.

Thereafter, Xi’s prospects brightened further when he became the country’s vice president in 2008, focusing his energies on conservation issues and international relations. Two years later, Xi became vice chairman of the powerful Central Military Commission, a post previously held by Hu, and a post seen to be a clear stepping-stone to the presidency.

In November 2012, at the party’s 18th party congress, Xi was again elected to the standing committee of the Political Bureau (now to be only seven members) and he succeeded Hu as general secretary of the party. Six months later, Xi was dutifully and unsurprisingly confirmed as China’s president by the National People’s Congress. He was elected to a further five-year term in 2017, and now, in defiance of a policy since the Cultural Revolution, he decided on getting a third five-year term.

There were, obviously, no alternative candidates vying for the job. In this, he is putting a thorough personal stamp on the party and the country’s government. Even the national constitution now includes wording directly traceable to Xi’s thoughts on governance.

At this week’s party congress, Xi set out an agenda for the future of the country, arguing it was facing a troubling international environment; he took steps to thoroughly reshape the party’s innermost council and to install a membership thoroughly loyal to Xi; and to stress the need for further enhancements in national security capabilities.

In examining the actual language of Xi Jinping’s report to the party congress, the Economist noted (and we quote it at length because of its analysis) that,

“…the party’s 97m members will be reminded [of this language and thoughts] during endless study sessions in the weeks ahead, [because] these reports are important. Mr Xi’s was the product of nearly a year of work, involving research by more than 50 institutions and feedback from thousands of people. Cadres ignore at their peril any linguistic tweaks, changes of emphasis, new terms or omissions. The full version of this latest report contained about 30,000 characters (around 25,000 words in the official English translation). They will be pored over carefully.

“…Some of these [word choices] reflect Mr Xi’s view of an unsettled world: ‘drastic changes in the international landscape, especially external attempts to blackmail, contain, blockade and exert maximum pressure on China’, as his report put it.

“One such word is anquan (security). It appears 91 times in the document, compared with 35 in the farewell report delivered by Mr Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, in 2012 (Mr Xi took over after that year’s congress). Another rise has been in uses of the word junshi (military). There were 21 this time. In 1982, at the first congress of the Deng Xiaoping era, there were just four. The word douzheng (struggle or fight) appears 22 times in the latest report. ‘We have shown a fighting spirit and a firm determination to never yield to coercive power,’ it says, in a clear swipe at the West. Mr Hu used douzheng only five times in 2012.

“Mr Xi offered no hint of any political relaxation. The term zhengzhi tizhi gaige (political structural reform) made a dramatic debut at the congress in 1987, with 12 mentions. This time Mr Xi did not use it, the first such omission since that time. He had much to say about traditional ideology: eg, ‘Marxism works’ (though it should not be treated as ‘rigid dogma’). Harking back to communist ideals, he referred eight times to a need for ‘common prosperity.’

“But Mr Xi’s report reveals anxiety. ‘Uncertainties and unforeseen factors are rising,’ it says. ‘We must be ready to withstand high winds, choppy waters, and even dangerous storms.’ It refers to one of Mr Xi’s preoccupations: escaping the ‘historical cycle of rise and fall.’ His remedy is ‘self-reform,’ which involves eliminating corruption, ideological wavering and disloyalty to himself. After a ten-year fight against graft that has toppled many serving and former high-ranking officials, including political rivals, he signalled that there would be no let-up. The report mentioned fu (corruption) 29 times, a record for post-Mao Zedong congresses.

“Lest anyone begin to waver in their faith in the party’s—and Mr Xi’s—ability to cope with the dangers ahead, the report kept repeating another of his cherished terms: zixin (self-confidence). Not everyone has got that message. After a rare protest on October 13th, involving a banner on a bridge calling Mr Xi a dictator, security in Beijing was tightened still further.”

Meanwhile, amid this congress, in a thoroughly confounding and rather troubling moment, Xi also had his immediate predecessor and mentor, Hu Jintao, forcibly removed from the congress in full view of the entire party congress, just as Xi was about to deliver his address. What that was meant to signify continues to mystify observers, so far. Maybe it was a rebuttal to Hu’s more conciliatory policies, or maybe it was meant to say, “I am the boss.” But no one knows for sure.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Commenting on the new line-up of the party’s all-important Politburo Standing Committee with Xi as general secretary, the BBC noted, “China’s leader Xi Jinping has moved into a historic third term in power, as he revealed a new leadership team stacked with loyalists. On Sunday the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) unveiled its Politburo Standing Committee, with Mr Xi re-elected as general secretary. Observers say the line-up, handpicked by Mr Xi, shows he prizes loyalty over expertise and experience.” Loyalty appears to have trumped any real appreciation of expertise or a visible sense of a full-throated meritocracy at work.

Following the formal introduction of the new team, Xi Jinping vowed to achieve the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation on all fronts.” The standing committee now comprises largely new faces at the top level and just two — anti-corruption chief Zhao Leji and political theorist Wang Huning — are holdovers. Premier Li Keqiang, heretofore the country’s number two leader, was not visible during this beauty pageant and he is one of four men who have now retired from the committee.

Loyalty

While reshuffles of the standing committee after serving for a five-year term are not unusual, by removing Li Keqiang and the others, Xi has now ensured he is surrounded by a group where nobody with a different perspective from his is included. As Wen-ti Sung, a lecturer at the Australian National University noted, Xi “felt no need to assign a spot to an alternative faction, which shows his priority is projecting dominance over magnanimity, when he is facing international pushback.” Loyalty to Mr Xi trumps ability and experience.

The official titles of the standing committee members will only be confirmed at next year’s parliamentary National People’s Congress meeting, where, given what has happened this past week, Xi will obviously be confirmed as president again. But many believe Li Qiang — who walked out right behind Xi during this highly-choreographed ceremony — will become the new premier in charge of China’s economy.

Li Qiang is currently the party secretary in Shanghai and, perhaps as a harbinger of things to come, he has overseen the city’s controversial lockdown where tens of millions of people experienced significant food shortages. On this basis, some observers are already saying that given Li’s new role, Xi is sending the sign that national security will be prioritised above economic growth.

Professor Yang Zhang of the American University also noted, “This promotion alone is significant for us to reconsider the power structure of China under Xi’s third term.” Interestingly, Li Qiang is also the first official to be promoted to this paramount committee without working experience in the central government.

Another new appointee is Cai Qi, Mayor of Beijing. While his performance during the city’s hosting of the Olympic Winter Games has garnered praise, his plan to reduce the city’s population by forcing out low-income earners has been criticised. Moreover, as Neil Thomas, the Eurasia Group’s China watcher observed, “Cai was not even among the Communist Party’s top 370 leaders before the last party congress. Now he is the fifth most powerful person in China.” Loyalty matters.

The BBC added that “no woman has made it to the standing committee — likely to be a disappointment to China’s feminists but not a surprise. Indeed the lone female member of the 25-member Politburo, Sun Chunlan, has retired so that grouping is also without any female participation.”

“This is a very sad and shocking arrangement,” Prof Yang said.

Meanwhile, ordinary Chinese watched the proceedings via state-run television, even as it is also true that patience with the government’s stringent Covid lockdown measures may be wearing thin. There was even a rare public protest in the capital, calling for an end to that policy and Xi’s removal, although Xi has been clear there will be no immediate relaxation of these measures. While the local social media app, Weibo, only carried praise for the leadership, on Twitter, accessed by virtual private networks, there were criticisms. One such comment read, “Xi’s Army lives up to its name, and the whole country welcomes the return of the empire.”

Growing world tension

Xi’s unprecedented third term as party (and thus national government) leader comes at a time of growing tension with much of the West — and most especially with the United States. Recent US official statements now say, “The People’s Republic of China harbors the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order in favor of one that tilts the global playing field to its benefit, even as the United States remains committed to managing the competition between our countries responsibly.”

Categorising China as a strategic opponent (although not an enemy) adds to the pressures. Moreover, the Chinese must also come to grips with new efforts by the US to limit their access to high end microchips — items crucial for a vast range of defence, high-end and other consumer products.

In addition, for China, the strategic landscape has become more complex than it was during Xi’s earlier terms as China’s leader. The Quad, that tacit alignment of the US, Japan, Australia, and India, with Aukus — the partnership of Australia, the United Kingdom, and the US — now serve as a network of defence and security relationships whose focus is the entire Indo-Pacific region. That, obviously, centres on China’s efforts to build up its military capacity for operations in the South China Sea and beyond, and its efforts to bolster China’s connections with a whole roster of small states in the Pacific.

Moreover, China’s continuing insistence Taiwan will be “reunited” with China by peaceful or other means, if necessary, makes those two multilateral partnerships more important. This is in addition to the American insistence on supplying Taiwan with defence materiel remains consistent with its commitments both to the island and with its understandings with China once relations were established. As the Russian invasion of Ukraine grinds on and the possibility of Russia’s actual defeat in that effort looms, Xi’s China may need to reassess its relationship with its northern neighbour as well.

Further, Xi’s China also finds itself still embroiled in its hard lockdown policies towards entire cities in efforts to quell the Covid pandemic there. Meanwhile, its banking and real estate/property development sectors have demonstrated significant wobbles stemming from an investment bubble. Finally, China’s earlier “one child per family” policy is likely to produce a retirement financial crisis in the next several years as retirement numbers grow and workers must carry that weight.

Xi Jinping’s next five years as the leader of China will be filled with opportunity, but also significant challenges, especially as his nation, under his leadership, strives to increase its impact on the global political economy. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.