MY STORY

When Abraham lost Israel – the saga of a missing child

Stories of migration have always carried their share of trauma and miracles. The Lieberman family, the clan from which I come, has its own astonishing tale. It is one we reflect upon often, marvelling at the moments of terrible loss and stunning providence. Long settled as family legend, over the decades we have regularly returned to our elders to get a better grasp on the details.

Abraham Lieberman was, by all accounts, a troubled man. The father of five children and one on the way, he was, as with many other Jews in Russia in the 1890s, confronted with some of life’s big quandaries – the survival of his family, for one. The Jewish communities of the Baltic and their neighbouring states had been suffering from a slate of pogroms, with thousands being killed, and it was clear that the Liebermans’ hometown of Katerinoslav (now Dnipro in Ukraine) was eventually going to be engulfed in the violence. Like others in the same situation, responsibility rested on Abraham to branch out and find safe harbour for the family.

South Africa had somehow struck a chord in the broader Russian Jewish community. The promise of the gold rush and the many spin-off industries was enough to fire up the collective imagination. It was also as different a place from Russia as possible; another hemisphere, mild winters, a new colony, a fresh start. That the Anglo-Boer War was raging in South Africa at the time was clearly not a deterrent – what has that conflict got to do with us? Our troubles are here.

Abraham’s wife Rachel, pregnant at the time, told him: “If you’re going, take Israel with you. He’s the naughtiest.”

Israel, or Issy to the family, was their eldest child. He had just turned seven. A freckled, ginger lad, Issy was brazen, energetic and mischievous. The parents agreed that it would be more useful for Issy to travel with his father than to stay home. And so the large, red-bearded Abraham and small, pale Issy with his shock of ginger hair embarked on their long journey south. By road, rail and sea, they arrived in Cape Town in 1899.

It’s here where the story had its first major twist. The Cape Colony was under British rule, and neither father nor son spoke a word of English. After disembarking, Abraham told Issy to wait with their luggage by the harbour office while he went to find some lodging. “Don’t move from this place until I return,” were his instructions to the boy.

Issy waited. Hours went by. Eventually, night fell. Still, the child waited. His father did not return. The following morning, now aching with hunger, Issy continued to wait. Abraham had clearly disappeared. The boy had no choice but to leave and try to find his father.

After ordering Issy to stay put, Abraham had left the port in search of somewhere to stay. This was not meant to take much time. It wasn’t long, however, before he was noticed by a British patrol. Already on high alert – the Boer rebels had come within 80km of Cape Town – they quickly assumed that this large redbeard was from the enemy camp. They arrested Abraham on the spot, transporting him to a nearby concentration camp. He resisted, tried to explain, but to the overwrought British soldiers there was no way they could tell whether this panicked foreigner was pleading in Afrikaans or Russian.

For three days the British held Abraham in the camp, until it became clear to them that he was neither, after all, a Boer, nor was he a rebel. “Redbeard” over here was Russian, and they had no quarrel with his people. So they released him. Abraham hastily returned to the port to find Issy, but the child was gone.

The father searched Cape Town for his young son for three months. The city was teeming with the multitudes; soldiers, traders, foreigners and families. The boy had vanished. Eventually, Abraham concluded that there was no way that the little child could have survived – a helpless juvenile, non-English speaking immigrant. He wrote home to Rachel in Katerinoslav, explaining to his wife that Issy had been eaten by wolves, and was dead.

In the meantime, Issy, after failing to find his father, was now entirely guided by his stomach and the need to eat. He started searching for food. For days he survived on scraps that he found in bins on the street. One day he came upon a large, discarded barrel, tipped it on its side and laid down some material he had found on the street. It became his night shelter. The days and weeks ahead saw Issy get smarter to his surroundings, and he started pilfering bottles of fresh milk delivered at sunrise to the front steps of the wealthy colonial homes. He even found a puppy which he took in, and it became his companion.

Eventually, a group of coloured street urchins noticed this very white-skinned ginger kid who was clearly running solo, but doing so on their turf. They approached him and promptly inducted him into their ranks. Issy joined them and found comrades, community, and the chance to learn some English. They introduced him to their neighbourhood on the other side of town.

Over time, Issy was noticed by a coloured family who realised something must have gone terribly wrong for this pale Russian child to have found himself alone on the streets of Cape Town, clearly far from his people. Themselves mired in poverty, they decided to take him in and make sure he survived. He lived with them for several years.

Even with the sudden blow of losing his father in a foreign land, learning a new language through the abrupt absorption into an entirely new culture, Issy never forgot his name nor where he was from: Israel Lieberman, from Katerinoslav, Russia.

Five years passed, and Abraham, now settled in Johannesburg, finally had the means to bring the rest of the family from Russia to their new home. These sorts of extended gaps in family life were the norm at the time. It was clear upon their reunion, however, that Abraham’s reality was mismatched from that of Rachel’s, and it centred on the question of Issy. They owned one photo of Israel, taken on his seventh birthday, which Rachel had kept close to her person since he had left home in 1899.

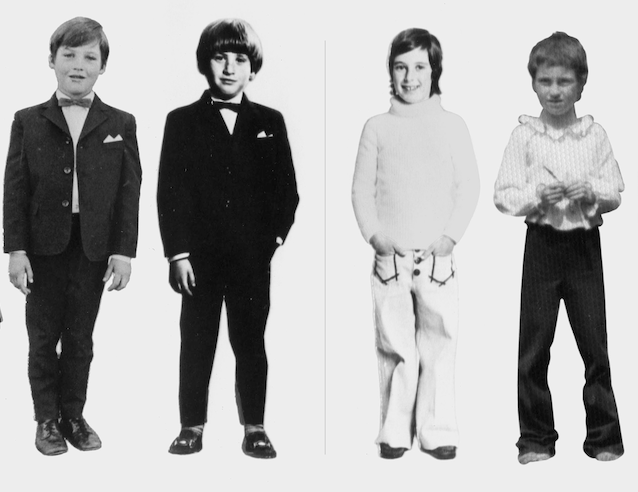

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Upon settling the family in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, Rachel set about placing ads in the local newspaper, the Rand Daily Mail:

“Israel Lieberman, your family is looking for you, come to this address.”

She simply never believed that Issy was dead. These ads were placed in the newspaper from the moment she arrived in South Africa, and she continued with this campaign for years. Abraham thought this was a fool’s errand – in his mind Issy was long dead, but Rachel was determined.

Eleven years had now passed since Abraham and Issy had landed on that fateful day in Cape Town. While the middle years were not as clearly chronicled as those first few dramatic months in Cape Town, at some point Issy found himself a trade as a licensed digger on the alluvial diamond mines. He was now closer to Johannesburg. On his way north to find digging work he had, for a time, survived on fish he caught in the Orange River. From taking in that first puppy in Cape Town when he was seven, he was never without a dog as his companion.

Eventually, he found himself on a dig in the vicinity of Lichtenburg, and it was here where he set up camp. He got to know others in the industry, and they got to know him. He had taught himself to read but never attended school.

Issy was now 18. Early one morning, while digging, his friend approached him holding a Rand Daily Mail. “Issy, is your full name Israel Lieberman?” he asked. Issy replied that it was. The young man had just returned from Johannesburg, and as he handed over the paper, he explained: “There is a family looking for someone with your name. See here in this column!”

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

There was a small block with large print, with his name – his name! – the message to return, and an address. Issy was electrified by this news. He immediately jumped up, explaining to his friend that he had to leave for Johannesburg without delay. He raced to the train station, found out which was the next train departing for Johannesburg, which happened to be a freight train. Undaunted, and unseen, he jumped aboard as it left the station, hiding in an empty cargo carriage.

It took most of one day to get to Johannesburg. As they pulled into the city, his first time there, he heard the stationmaster call out “Braamfontein!” whereas in fact he had called out “Randfontein!” Mistakenly, Issy got off at the wrong station. Undeterred, he started walking along the tracks to Braamfontein. Seven hours later, he clambered up onto the platform. He asked directions to the address in the newspaper ad, and followed them. By now, night had fallen.

The semi-detached house was surrounded by a hedge and small garden, and was lit up inside. In great anticipation, Issy felt the need to prepare himself. First, he wanted to take a look at the people who posted the ad. He crept into the shrubbery, and peered through the window. He saw a family. Inside, one of the older boys noticed a face outside gazing in at them. Thinking it was a thief, on impulse, the young man decided to take things into his own hands. He slipped quietly out the back door, holding a plank of wood. He sidled around the house to where Issy crouched, transfixed, staring through the window. The plank landed squarely on the side of Issy’s head, and he was knocked out cold.

The children dragged Issy’s limp body into the kitchen, and laid him down on the table. At that moment, Rachel walked into the kitchen and saw this dishevelled, unconscious lad lying prone on the tabletop, and froze.

“That’s Issy.”

Pandemonium. They immediately revived him and attended to his bruised skull. He emotionally confirmed to his mother that he was indeed Issy. The reunion was euphoric – the disbelief, Issy’s stunning good fortune, Rachel’s untold joy and profound vindication, the jolt from the blue for the family. All shared in this heightened moment – all, but Abraham. He was not remotely convinced that Issy was who he said he was.

“This man is an impostor!” he later implored with Rachel. “Issy is dead, there is no way he could have survived. I searched for him. Issy died over a decade ago. This boy is not our son!”

Abraham stood alone in his conviction, and he held to it. It was clear to Rachel and the rest of the family that they had witnessed a rare miracle, and that this pale, freckled, strapping ginger lad was exactly who he said he was. Welcomed home with tears, a flood of questions and mountains of food, the family embraced Issy as their very long lost and now miraculously found son and brother.

***

Zeide Issy, my grandfather, died 10 years before I was born. My father Julius was the youngest boy of eight children – four boys, four girls – born to Issy and my Bobba Chisha. She too was a Russian immigrant. They met through the Johannesburg community and married in 1923. By then a highly resourceful and intrepid businessman, Issy had opened a timberyard, and later owned and managed two hardware stores, passing the business down to his sons.

According to his last surviving son, my 92-year-old uncle, Robert, Issy always had with him a small jar of diamonds – possibly something held over from his days on the digs, keeping a stash of precious stones on hand for hard times. He also maintained an enduring love and respect for the coloured community, an expression of his deep gratitude to his young friends and the family who took him in and cared for him as a child.

In my generation, I am one of 22 first cousins, all of whom descend from Issy. One of the startling points of evidence about Issy’s descendants is how unconventional we all are. Growing up in Joburg, anyone who knew the Liebermans would comment on the certain eccentric streak that ran through the family. Among us is a wild spread of colour, noise and adventurism. The intrepid line is our north star. Our ranks include artists, social entrepreneurs, filmmakers and city builders, directors of stage productions, ethnobotanists, musicians, activists, mystics and magicians.

Very few straight-up career tracks – no doctors, accountants or lawyers – and I doubt any five-year plans have been floated or followed.

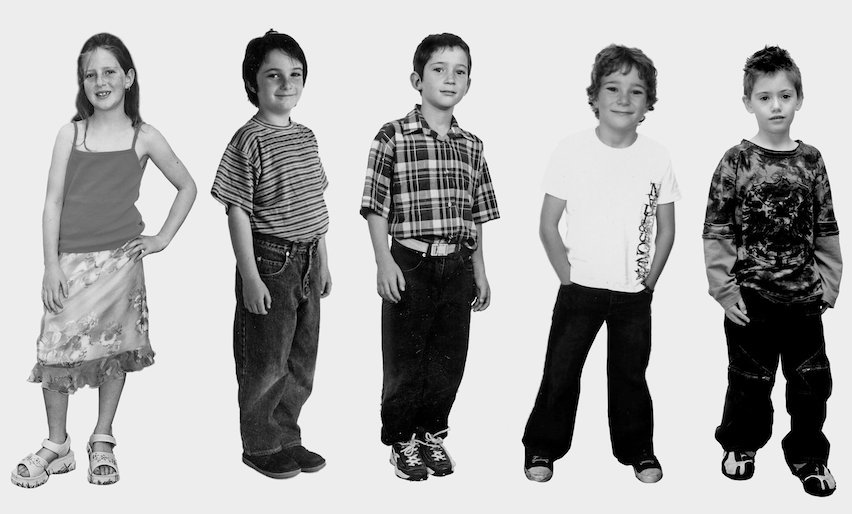

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Lieberman children, aged 7. Image: Kim Lieberman

Epigenetics, the study of heritable changes that modify and alter the genetic impulse brought on by extreme life experiences, propose that changes to the wiring do occur in subsequent generations. The science seems to have revealed a profound proof in Issy’s significant life experience, and in his resultant progeny. After centuries in the Baltic, a child is plucked from a long line of ghetto-dwelling Jews, and transported to the bottom of Africa in the middle of a territorial war between two alien colonisers. How Issy survived as a lost and lone seven-year-old, and then thrived, is a staggering combination of will, resilience and sheer luck. That his encounter with such radical challenges, at such a young age, somehow translated into this atypical breed of a family remains a fascination, a study in itself. For us it has become Lieberman lore.

One of the ways that Issy memorialised his story was through a custom that he instilled with his children. It was a simple act, intended to bond his descendants over the ages, and one that has so far served us for four generations. On their seventh birthday, every Lieberman boy was to have his photograph taken. This was matched up to that single photo Issy had of his childhood, taken on his own seventh birthday. Over time a long line of Lieberman lads spooled out, spanning the 20th century.

At some point, my father took on the job of compiling the photographs, and he approached my sister Kim, then 10 years old, now an established and well-respected conceptual artist. He co-opted her by saying: “You have a steady hand and a good eye. Cut out these photos of the Lieberman boys accurately. Then line them up next to each other.” She set upon the task with a scalpel, finely slicing along the profiles of generations of seven-year-olds. She and my father placed them side by side, creating one flowing genealogical photomontage.

As a child, I remember bringing my face up close to the grainy images of my father, uncles and cousins. Being the youngest boy of my generation, I noted both the shifting realities and evolving fashion; the scuffed knees and rough-hewn gabardine of my dad’s blazer, to the relatively suave bowties and Brylcreemed hair of my confident elder cousins.

As the family grew and Liebermans begat more Liebermans, boy after boy was added to the ever-extending phalanx. Eventually, as an adult and preparing to have her own family, it dawned on Kim that she was not just the steady-handed collagist assigned by our father to neatly line up the little boys in a row. She too was a Lieberman, and a proud one at that, as were so many of the other Lieberman women. So she informed our father and Robert, the de facto patriarch of the clan, that she was expanding on Issy’s tradition by including the girls, and that she was convinced that not only would he not mind, but she would have Issy’s blessing. And so the line grew to include both genders from all the kids in Issy’s lineage, including all possible retroactive photos.

Lieberman children, aged 7, through the ages – 2022. Image: Kim Lieberman

***

One of the shadows that hung over the Liebermans from the time of Abraham and Issy’s separation, is how distanced Abraham became from the family. Apparently, his not accepting Issy was but one of many points of conflict, and over time these all settled into a pervading faribel, an ongoing grievance layered with multiple unforgivable incidences that spanned the years. We cannot know why Abraham was such a hard man. It could have been the accumulation of the many traumas he suffered throughout his life, amplified by the loss of Issy during such a severe transition. Or, it might simply have been his nature. By now, so far down the line, it’s all conjecture. Either way, so deep did this faribel go, that on his death the family refused to say Kaddish, the prayer for the departed, or to place a headstone on Abraham’s grave.

In the early 2000s, after several years trying to be a Buddhist in the Tibetan tradition, I made a slow return to my Jewish roots, moving my base from the Himalayas to Israel. It included a stint in a Jerusalem yeshiva, and living for a time in Tsfat, the ancient mystical town in the Upper Galilee. I became a Baal T’shuva of sorts, a returnee to the faith. It was here that I discovered and started gathering enough doctrinal evidence to advocate for the family to finally put a headstone on Abraham’s grave, and to honour our ancestor by saying Kaddish for him.

What I had not yet tasted, however, was the depth and commitment to the enduring family faribel. It met me like a plank of wood to the side of the head when I approached Robert on the subject. He confronted me with a barrage of reasons as to why this was totally out of the question. But it landed on this one statement, one that had carried through for almost a century.

“He rejected your grandfather outright! We will never honour his memory!”

I was struck by the force of the conviction. Abraham died in 1924; Robert was born in 1929. They had never met. It was the last time I brought the subject up with him. And then my sister Lila entered the conversation.

Lila, the youngest of our generation, six years my junior, was undergoing the early stages of her thwasa initiation. Thwasa is the indigenous training in the rites and practices to become a sangoma, a deeply mystical and ancient tradition. During her process, she met with yet another, elder South African Jewish sangoma – one who happens to also be a urologist who held a post at Stanford Medical Center.

They met at his forested mountain lodge in Limpopo, in the northern region of South Africa. He conducted the ritual divination by “throwing the bones” in his ndumba, or ceremonial hut, an act which is very much not part of the Jewish tradition. Throwing the bones, usually a collection of small animal bones, carvings, stones, shells and various trinkets, is the method of communicating with one’s ancestors. Ultimately, based on what comes through, it is the opportunity to appease your predecessors from their perch in the otherworldly realms, by acting on their requests. A skilled sangoma can divine from the bones some remarkably accurate messages, and what came through to Lila was extraordinarily, and Jewishly, on point:

“Your paternal great-grandfather is deeply unhappy. He is ‘stuck’ between the earth and the sky. You need to help him to settle his soul.”

An astounding communique, considering it would be precisely what any rabbi would have said had they understood that Abraham was, indeed, not at peace.

Lila shared with me the message she had received through the bones and was taking this directive seriously. She advised that she was planning to bring this up with Uncle Robert. Considering that the faribel was almost 100 years old and that Abraham had been dead for 82 years at the time, I gave her fair warning. “Robert is going to get agitated with this proposal, like he was when I approached him. Expect some pushback – but don’t take it personally.” To add to this, Robert was and remains an avowed atheist. The likelihood of him being moved by the message in the bones was as unlikely as him accepting a ruling by a rabbi.

Lila called me after their meeting. I was stunned to hear of his reaction. A century-old tradition of resentment was abruptly turned on the quiet appeal of our youngest Lieberman. “Settle this thing, Lila,” Robert had said to her. “Find the grave, design the headstone, I will pay for all of it. Then let’s gather his descendants.”

An African divination ceremony, eight decades after his burial, initiated the end of the struggle for Abraham’s neshamah, his soul. Descendants gathered at the grave from across the world, and the required quorum, a minyan, was finally able to say Kaddish over a beautifully crafted headstone. The circle of a century of loss, recovery and resolution was ultimately closed for the Lieberman family. DM/ML

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

What an incredible story. Thank you so much for sharing it with us.

I loved every sentence of this story – what an adventure and how inspiring.

Family is everything…it saddens me that the family bonds enjoyed by our black brothers and sisters ( especially under Apartheid) have slowly unravelled…HIV deaths and Government Grants making it easy not to commit to marriage and shared parental responsibilities. Homeless children resort to glue-sniffing and drugs rather than being able to rely on the Ubuntu that was once the pride of the majority of South Africans.

This story has inspired me with hope….and filled me with sadness at the same time. Thank you.

What a huge pleasure to read.

So well laid out and very moving.

It should reach a wider audience.

Well done for sharing.

A story of hope and humanity. Thankyou

I’ve wept copiously reading this – what a beautiful story!

Thank you for such a brilliant and moving story.

What a lovely story

I enjoyed it immensely

It is interesting that the traditions of ancestors importance is the same for so many different cultures

We have more similarities than differences across society which we all would do well to remember

Amazing story and a great revelation about Sangomas.