POWER CRISIS OP-ED

As SA teeters on the brink of full-blown energy disaster, it’s vital the right decisions are made – now

Ours is a highly complex energy system that has been pushed to extremes. If it starts to collapse, it will be much harder to steer the energy transition in the right direction. We missed three crucial decision points — in 1999, 2015-17 and 2019. Let’s learn from these.

When it comes to the energy crisis, South Africans deserve better than the blame game that we see on our TV screens. During a time of instantaneous tweets, daily predictions by modellers who are assumed to be omniscient, and algorithmic decision-making for everything from stock markets to advisories from TripAdvisor selecting your favourite restaurants, the past seems increasingly less useful for making sense of the present, let alone the future.

No one will question the fact that the energy system is a complex system. This means the linear laws of cause and effect do not apply. It also means accepting that every complex social system has a history that cannot be escaped, no matter how amnesic the nation’s memory may be. Whether we like it or not, when it comes to our energy system it seems like the nation’s collective memory needs a reboot.

But first, a quick summation of our present condition.

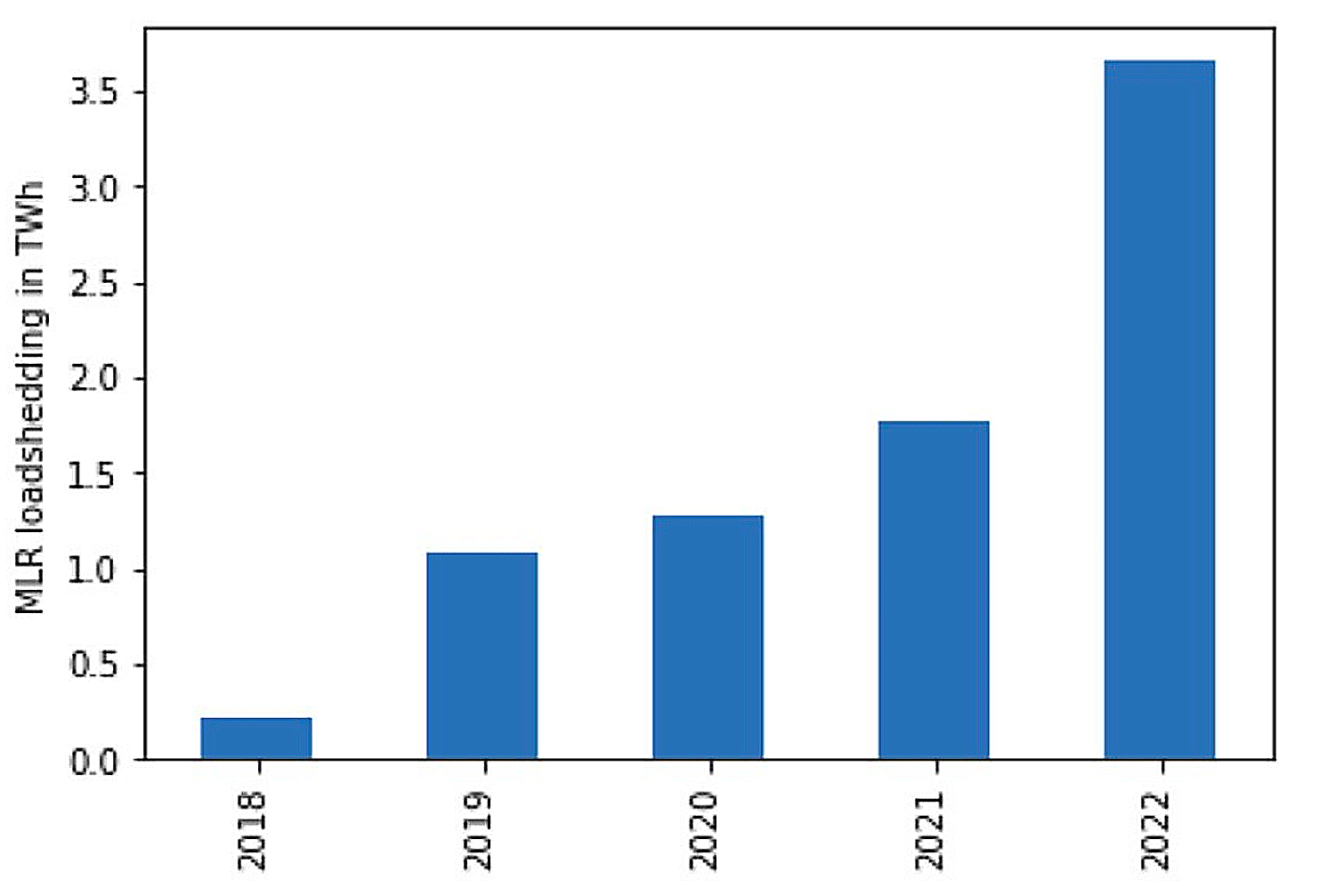

Load shedding has never been this bad, breaking the 3.5 TWh mark in 2022, with still three months of the year to go.

By 22 September, this was already the worst month of load shedding on record. With every 1,000 MW (or 1 GW) of capacity that gets taken off the grid, we go up a stage — Stage 6 means 6,000 MW of capacity are not available. By the time we hit Stage 4 we are losing R2-billion per day of economic production.

Large and small businesses are suffering, with many closing down. Jobs are being lost and the growth rate will plummet, thus undermining all strategies to recover from State Capture and the pandemic. Everyday life has become unbearable for many, both rich and poor. There are 15-year-olds running around who have never known what life is like without blackouts.

Source: Meridian Economics, data source from Eskom Data Portal. MLR = Manual Load Reduction, better known as ‘load shedding’.

President Ramaphosa flew back from the Queen’s funeral for crisis talks when we once again hit Stage 6 — when 45 units tripped — déjà vu for those who recall his decision to rush home from an overseas trip when we hit Stage 6 back in 2019. We also hit Stage 6 in June/July this year.

What South Africa needs to realise is that no matter what the president or the Cabinet may decide today (and no matter how sound their policies are), nothing will stop load shedding tomorrow.

If all the reforms triggered by his game-changing statement in July are realised, there are two best possible outcomes we can hope for.

First, that load shedding will only end in two years’ time (at the earliest) when 5-10 GW of new renewable energy capacity has been built and commissioned.

Second, that Eskom’s Energy Available Faculty (EAF) does not dip below 60% (even though the ideal minimum would be 72%). As explained below, this might result in manageable levels of load shedding for the next two years, followed by reduction and a possible end to load shedding. Although these phrases are bandied about by experts and journalists, South Africans remain confused — they deserve better. So let me explain.

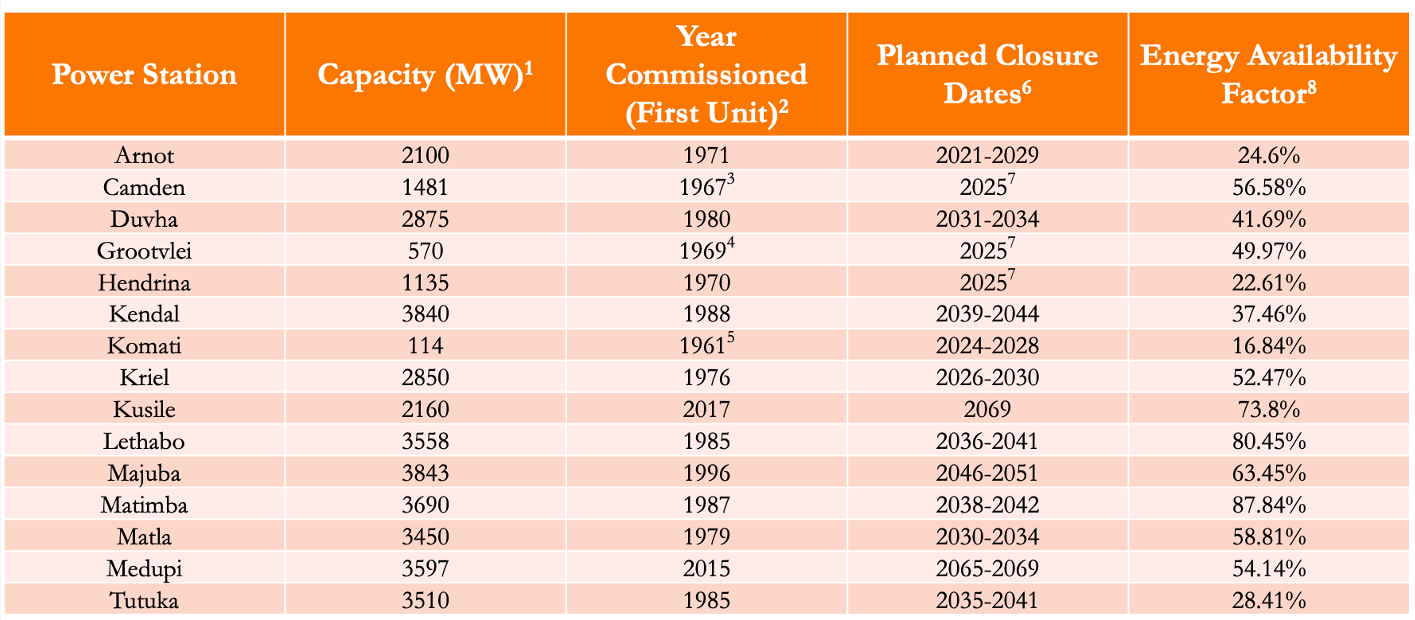

Eskom operates 90 generating units located within 15 coal-fired power stations. A relatively new power station should have an EAF of 80% or more if managed and run properly. What this means is that it should be able to generate 80% of the energy it was designed and built to produce. Like a car, the older it gets, the lower its average EAF becomes, because more and more time is required to repair, maintain and even rehabilitate its component parts. And, like any car, if it is not properly repaired and maintained, it degenerates faster than it should.

A power station also has a fixed life span with a so-called “dead stop” date marking a point where it costs more to keep it going than the value it is capable of generating.

It is a well-known fact that SA has an ageing fleet of coal-fired power stations. A strong narrative that many repeat is that the old power stations are the unreliable ones. The picture, however, is more complex as reflected in the table below:

The oldest power stations, like Arnot, Camden, Grootvlei, Hendrina, Komati and Kriel, are all operating at low EAFs, which is what reaffirms the dominant narrative that it is the old power stations that are the problem. But Medupi and Kusile are new power stations that should be operating at an EAF of 80% or above — Medupi is at 54.1% and Kusile is at 73.8% (but remains incomplete).

Shockingly, even a relatively young power station like Tutuka is operating at 28.4%. But Matimba and Lethabo, with closure dates similar to Tutuka, are at 87.8% and 80.4% respectively, which proves that it is indeed possible to have EAFs at this level if the plants are properly managed in a corruption-free and efficient manner.

There are three main reasons for the poor state of Eskom’s fleet of coal-fired power stations.

First, between 2015 and 2018 under the leadership of Brian Molefe (2015-2016) and Matshela Koko (2016-2018), power station managers were instructed to keep the machines running at all costs. This meant refusing managers permission to do routine repairs and maintenance in order to keep up the appearance that they had ended load shedding.

According to some former Eskom employees, Koko even had the procurement and engineering managers sign letters of resignation that he would counter-sign if and when he wanted to sack them. For station managers, he had his infamous “red” and “yellow” card system. Molefe and Koko ruled through fear, which led to the resignations of many competent managers.

Second, the Zondo Commission reports make it very clear that Eskom was a prime State Capture target. It was effectively looted to enrich the Zuma-centred power elite that coordinated the process of repurposing state institutions to suit the financial and political interests of this formal and shadow-state network. The many investigations and court cases confirm this finding.

Third, there is more than enough evidence in Kyle Cowan’s book about Eskom, titled Sabotage, plus numerous other reports, that there is an active network of people engaging in acts of sabotage to subvert the new Eskom leadership that has been in place since 2020.

The present management

This is not to say that the Eskom leadership under André de Ruyter is blameless. No management team in any organisation can claim it never makes mistakes. However, to argue that Eskom’s management is somehow willingly refusing to do its job for the sake of some ulterior motive is simply not credible.

Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe has publicly questioned whether De Ruyter is fit for the job. Many have called for his resignation. And former CEO Jacob Maroga (who resigned in 2009) has repeatedly insisted that load shedding can be ended if Eskom’s management decided to just fix the machines. However, on a TV show hosted by JJ Tabane on 21 September, where Maroga repeated his strident claims, Tabane neglected his duty as a journalist by refraining from asking Maroga how this could be done in practice without instigating more load shedding.

The indisputable fact is this: to properly repair any of the 90 generation units in Eskom’s 15 power stations that are underperforming, they need to be switched off so that they can be completely overhauled. This means the energy they generate is not available to the grid. Given the extent of the problem, to do what Maroga wants them to do, Eskom’s management would have to plunge South Africa into permanent load shedding while the machines get repaired. This is not a viable option.

The only way Eskom can secure the space it needs to properly repair and rehabilitate those machines (in particular the ones that are actually reparable, because some just need to be closed) is if there is new generation capacity on the grid. The problem, of course, is that Eskom has no power whatsoever over the procurement of new energy generation capacity. That is the responsibility of Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe.

So the obvious question is, when will this happen?

Mantashe should be complimented for making many of the right moves this year. Unfortunately, he could have made all these moves back in 2019, which would have prevented most of the load shedding we have today.

He was strongly advised to do so then by many, including myself in a face-to-face discussion, but this advice was ignored. Mantashe still talked then about procuring new coal-fired power as the solution. Since then he has realised this will never happen because no one (not even the Chinese) will fund new coal-fired power in South Africa. Even if they did, it would take 10 years to build. Needless to say, we do not have 10 years.

The only solution, Mantashe has belatedly realised, is to procure new renewable energy. It is much cheaper than new coal-fired and nuclear power. Global investment in renewables is now over the $500-billion mark, double total investment in new fossil fuels and nuclear combined. As renewables have dropped in price by 90% over the last decade, coal-fired power and nuclear have both steadily become more and more expensive.

Most energy experts are of the view that South Africa needs to build at least 5 GW of renewables per annum for at least the next 20 years. This has two goals. The first is short term, which is to give Eskom the space to repair those machines that are reparable to improve the overall EAF. Easy to say, but it means going up against corruption, sabotage and the obstacles imposed by inappropriate bureaucratic procurement procedures.

The second is to have enough new generational capacity on the grid to allow Eskom to close those power stations that must be closed before 2030 (Arnot, Grootvlei, Hendrina, Camden, Kriel, Komati, Duvha and — because it is probably irredeemably corrupt and therefore damaged beyond repair — Tutuka). Closing these power stations means losing 14.6 GW, which is over a third of the fleet’s capacity.

Renewables

So what is the state of play with regard to renewables? How soon can we expect them to start producing energy? There are now two ways to procure large-scale renewables in South Africa — via the auction mechanism in terms of Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Procurement Programe (REIPPPP) which requires Eskom to buy the energy generated (via Power Purchase Agreements — PPAs), and via so-called embedded generation with, in theory, multiple off-takers.

The preferred bidders for Bid Window 5 were announced in October 2021, consisting of projects totalling 1,608 MW of wind and 975 MW of solar PV. The call for Bid Window 6 was in April 2021, and the call was for 1,600 MW of wind and 1,000 MW of solar.

In July 2022, the president announced that Bid Window 6 would be increased to 5,200 MW. He also announced that the 100 MW cap on embedded generation would be removed, thus enabling large-scale private investment in utility-scape projects not procured via the REIPPPP.

Operation Vulindlela in the Presidency has claimed that it is helping get approvals for embedded generation projects that can generate a total of 9,200 MW. In short, this is a total of 16,983 MW (nearly 17 GW), excluding Eskom’s 1,800 MW that could be generated from repurposed post-closure power station sites.

Most experts agree that if 10,000 MW of this total are connected to the grid by the end of 2024, we can expect load shedding to end. It follows, therefore, that everything must be done to make sure these projects are approved, funded and implemented before the end of 2022.

So how did we get into the mess we are in?

To understand any complex system, the history of the key turning points in the past need to be understood. There is nothing inevitable about the outcome. Despite those who use deterministic arguments that predict the outcomes in advance, the reality is that when it comes to social systems, the outcomes are the function of decisions that could have been different. In the case of SA’s energy system, these are specific moments when decisions were made under specific conditions. There are three that are of great significance.

Missed opportunity #1 was in 1998 when government approved the White Paper on Energy, which made it very clear that unless new generation capacity was procured by 1999, there would be an energy shortage by 2008. The first load shedding was in 2007.

Eskom kept on pressuring government to be allowed to procure new generation capacity, but government accepted the advice of influential advisors that it would be preferable for the private sector, in particular BEE-empowered companies, to invest in new generation capacity.

The problem is that the prices were too low to attract investors. Trevor Manuel, then Minister of Finance, insisted that exports would suffer if prices went up. Without increased prices, margins were too low to justify profitable private investment in power plants. And so the decisions were delayed and delayed, until then President Thabo Mbeki apologised to the nation in 2008.

Debt crisis

After Pravin Gordhan (as Minister of Finance) signed the funding agreement with the World Bank, Eskom was rushed into building Medupi and Kusile, despite having lost a lot of technical capacity to do the job properly. As a result, costs ballooned: what was supposed to have cost R163.2-billion with a completion date of 2015, has ballooned to an eye-watering R450-billion (Kusile is still not complete). Herein lies the origins of the Eskom debt crisis.

Missed opportunity #2 was in 2015-2017, when CEOs Molefe and Koko refused to sign the Power Purchase Agreements for the shovel-ready renewable energy projects. At the time, then president Jacob Zuma was obsessed with the implementation of an agreement he signed with Vladimir Putin to build a Russian nuclear fleet to resolve SA’s energy problems.

Influential presentations by Bain and Co to Zuma affirmed (with suspect calculations) the financial and technical viability of this idea. As Meridien Economics has now confirmed, if these PPAs had been signed then, 95% of current load shedding would not be happening.

Many of those accusing De Ruyter of purposely sabotaging Eskom to prepare the way for privatisation supported the rise to power of Zuma in 2011 and never opposed his delusional obsession with nuclear power, nor did they challenge Molefe and Koko to sign the PPAs. Some even call for the return of Matshela Koko as CEO of Eskom. Needless to say, the Zondo Commission recommended criminal action against both him and Molefe.

Gwede Mantashe

Missed opportunity #3 was in 2019. Mantashe was appointed Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy in 2018. In 2019, he was strongly advised to immediately clear the way for the procurement of large quantities of renewables if he wanted to be seen as the person who brings load shedding to an end. Instead, he kept reiterating the need for — and viability of — coal-fired power and nuclear.

Citing the red herring of “base load”, he refused to accept the need for renewables delivered either by Independent Power Producers or Eskom. If he had accepted the advice given — which was to implement his own policy, namely the Integrated Resource Plan — renewable energy plants would have been connected to the grid by now. The result would have been a much reduced level of load shedding.

Instead, after dragging his feet, Bid Windows 5 and 6 are now under way, and the cap on embedded generation has been scrapped (despite many years of defence of a 1 MW ceiling by Mantashe). Despite claims to the contrary by those who advocated this reform, there is no evidence that the much-anticipated private sector rush to register their embedded generation projects with Nersa has materialised.

In short, to paraphrase the Minister of Finance, we do not have an Eskom problem — we have (a much wider) power system problem.

When a complex system like our power system is pushed to extremes, like it has, it is almost impossible to predict what happens next. It is a hard story to tell both to South Africans and external parties.

After listening to my attempt to narrate these complexities, a very frustrated donor said to me during the climate talks in New York last week: “So Mark, what is the pathway going forward?” My answer was that no one can really say, but this is what should happen:

- Ensure that all the Bid Window 5 projects reach financial close by end October (latest) and start construction before end 2022 (2,500 MW);

- Find another (at least) 2,500 MW of embedded generation projects and ensure they start construction by the end of the year;

- Enable Eskom to implement its re-purposing strategy (at least 1,800 MW);

- Cabinet approval in October of the Just Energy Transition Investment Plan drafted by Daniel Mminele and his task team, for presentation at COP27 in Egypt in November, bearing in mind the importance of only approving what the donors are offering if the offer includes funding that cannot be obtained in another way from South African financial institutions;

- Final establishment of the publicly owned National Transmission Company of South Africa (NTCSA) in a way that will allow it to acquire large quantities of funding to rapidly expand the transmission grid to prepare for the rapid uptake of renewables (which means ramping up delivery of new transmission lines from the current 400 Hms per annum to 1,500 Kms per annum) — this will mean making sure this entity is not overly encumbered by the nearly R400-billion debt that is sitting on Eskom’s balance sheet;

- An announcement in the mid-term budget speech of the Minister of Finance in October that the National Treasury will be taking over from Eskom around R200-billion worth of debt — this will make it possible for Eskom to establish the NTCSA in a way that enables it to be properly funded to get the work done;

- Accelerate the processing of Bid Window 6 bidders so that they can reach financial close as soon as possible (not later than January 2023);

- A coordinated strategic response by South African public and private financial institutions to the need for large-scale funding of the energy transition, with the development finance institutions (DBSA and IDC) taking the lead;

- Brokered by the Presidential Climate Commission, a fully fledged negotiated stakeholder compact on the JUST transition, with special reference to Mpumalanga — this compact needs to have clear-cut implementable projects in mind, including governance and funding mechanisms, for things like skills training, local economic development, socially-owned renewable energy enterprises, entrepreneurial hubs like the DBSA’s D-Labs and the setting up of new manufacturing industries that make components for the energy transition in SA and rest of Africa;

- We need to develop an agreed long-term perspective on how to fund the energy transition through to 2050, which is consistent with achieving Net Zero by then — our initial estimates are that this will require investments equal to R3.7-trillion, half of which would be investments in generation, with the remainder going into storage, the grid, early closure of coal-fired power stations and the just transition.

From a long-term progressive strategic perspective, there are many aspects of the above approach that have not been adequately addressed in the many discussions under way within the PCC, civil society fora and business talks. Things are moving so fast that most stakeholders cannot always keep up. It is, however, worth concluding by mentioning some of these challenges:

- Embedded generation: it is clear that these reforms have been haphazardly conceived and implemented — the real implications for the financial sector, the grid (both transmission and distribution) and the REIPPPP, developers and communities have still to be worked out. There is a potentially unhealthy narrative which simply says “just deregulate asap, create an energy market, and allow energy to be provided by private investors”. How this reconciles with the right of all South Africans to affordable electricity remains a mystery.

- Just Transition: just transition is referred to in every document and in every speech, but no one has spelt out what exactly it means. The Life After Coal campaign, a coalition of leading civil society organisations, are starting to formulate practical suggestions based on research by university researchers. This is a step in the right direction. However, how to translate this into the detailed implementable compact referred to above remains very unclear.

- Upscaling capacity for the grid: as already mentioned, the grid must be reconfigured. It was designed to serve coal-fired power stations located in the North East (see Map).

Location of power stations and main transmission lines. (Map: Supplied)

But the wind and solar resources are in the South West (see maps).

This will be about upscaling the construction of grid transmission lines and related sub-stations from the current 400 Kms to 1,500 Kms per annum.

The companies that do this work include, amongst others, ADENCO, AMP Property Management and Land Acquisition, ARB Electrical Wholesaler, Babcock, CONCO Group, KONUPI Contracts, OptiPower (Murray and Roberts), P&S Electrical and Siyavuya. There is no information available about their ramp-up capacity to deliver if the contracting and funding was in place.

- Privatisation: given the current emergency conditions, decisions are being taken that are driven by the technical and financial requirements to end load shedding. As a result, power sector reform processes are resulting in a new configuration of public and private institutions (e.g. unleashing embedded utility-scale generation outside the REIPPPP framework), the liberalisation of the energy market via amendments to the Electricity Act, and the gradual transfer of energy generation into the hands of private (largely foreign-owned) capital.

- Although Eskom is a state-owned entity, the bulk of its work is contracted out to the private sector (see example above — who builds the grid, contracted by Eskom). Nevertheless, as IPPs take over generation, will the NTCSA remain publicly owned? If not, that could well contradict the just transition.

- Finally, there is the vexed question of the municipalities. The majority did not get clean audits from the Auditor-General, and many have massively underinvested in their distribution grids. They are losing richer customers who are investing in embedded generation and solar hot water heaters. And they owe Eskom billions of rands.

No matter where you go in the world today, energy transitions of one sort or another are under way. None of them is free of conflicts, contradictions, policy mistakes and capture by powerful interests. South Africa is no exception.

Every aspect of daily life will be changing. Massive new (largely unpredictable) challenges lie ahead. Until SA fully embraces what is already unfolding at breakneck speed, it is unlikely we can fulfil our destiny as a global leader of this transition to a new energy and economic order.

Ours is a highly complex energy system that has been pushed to extremes. If it starts to collapse, it will be much harder to steer the energy transition in the right direction.

We missed three crucial decision points — in 1999, 2015-17 and 2019.

Let’s learn from these and then make the right decisions going forward. We cannot afford to look back in a few years from now and conclude that there was a fourth missed opportunity that effectively brought the energy and economic system to its knees. DM/OBP

Professor Mark Swilling is co-director of the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Most incisive article Mark. However until the present Govt is removed from authority I fear we are indeed facing many more missed opportunities. At least start by getting rid of Mantashe, he is an absolute barrier to progress.

Great article Mark. Why not also privatise some of the existing Eskom coal-fired power stations, with appropriate PPAs, to ensure the correct skills, procurement processes and capital are available to speed up the maintenance programs?

The most coherent review of our power supply crisis so far. Clear and implementable steps. And once again Putin is in the mix. He really does need to go.

Thank you Mark, great article as always. If it was implemented as is, we would be on the road to recovery.

One small issue of the elephant in the room – Kyle Cowan’s quote “there is an active network of people engaging in acts of sabotage to subvert the new Eskom leadership that has been in place since 2020” is relevant. Coupled with that, there is no direct mention of the unions. Obviously, there is also the fact that the real “embedded power” in Eskom is the embedded capture cronies.

In short – We South Africans will find a way to deal with almost any crisis, it is who we are. However, the unions have “captured” the state long before the Guptas did. See for example what is happening to the list of previous specialists to be re-appointed; it is halted by the unions for “protection” of their members.

Aslo, those supporters of capture, who are still trying to pretect coal contracts, etc. to reap their share, remain in place as gate-keepers against true reform. These are among the ranks of senior officials, politicians and union leaders.

So we sould ask ourselves why these measures as Mark proposes are not happening. One major reason is that it is blocked by a variety of people amongst the officials, politicians and unions – i.e capturers – who do not have the interest of the public at heart.

These must be removed or neutralised by removing them from powerful positions.

I applaud you and your department for your research and persistence! Always focused on the crucially important South African issues; from unbundling and explaining State Capture to this energy crisis. Most importantly you provide solutions based on sound evidence. Thank you! Please don’t stop.

An excellent summary of how we got here. Thank you Mark.

No dramatic events or failures. Just the everyday hubris, incompetence and corruption of government – all governments – since 2008/9.

One small but non-trivial point missing under the ‘Corruption’ sub-heading of what is quaintly termed ‘missed opportunity #1’ bears recalling: the deal to supply boilers for Medupi was concluded with the local subsidiary of Japan’s Hitachi, in which the ANC’s fund-raising front company, Chancellor House, was a shareholder. This naked conflict was brushed aside as irrelevant by everyone, including the World Bank and SA’s DFIs responsible for financing the deal. Needless to say, the procurement price was inflated, the installation and operational inefficiencies were endless and, most serious of all, the cornerstone was laid for the subsequent State Capture and corruption feeding frenzy.

Good to be reminded that our current plight is the product of failures in ANC governance since 2008/9, and not just the Zuma kleptocracy.

Thank you Mark. I completely agree with your article.

However even with the best will in the world it isn’t possible to have financial close on round 6 in Jan 2023 – there are lenders involved and loads of red tape.

So that’s load shedding for another 4 years.

What are your views on a different short term strategy 2 – 4 years. Let’s build distributed embedded generation with batteries everywhere. Pumped storage too if possible – down mine shafts.

We have already installed in the region of 500 MW of rooftop solar this year alone based on panel imports to end June.

The red tape here is actually manageable.

Allow most of these systems to feed into the grid. Several munics allow this and don’t pay for the kWh hence supporting low cost electricity for indigent.

I estimate we have somewhere between 1500 and 2000 MW of rooftop installed already.

We have the ability to ramp this without placing distribution at risk.

Indebted munics may even benefit if this is structured correctly e.g. line losses reduce. Tariffs could be structured carefully.

Oh and whilst we are at it encourage everyone to install them east/west.