ZIMBABWE IN RUINS OP-ED

Are free and fair elections possible in Zimbabwe in 2023?

Given the history of elections in Zimbabwe in the past two decades, there should be considerable misgivings that the 2023 election could be any different, especially in the light of the statements by Zanu-PF that they will not accept loss and feel entitled to rule forever. This cannot be seen as mere rhetoric.

For 22 years the only solution to the political crisis in Zimbabwe has been the resort to elections, and the forlorn hope that an internationally accepted election result would guarantee the legitimacy for the country to re-engage with the international community.

Unfortunately, it is also the solution advocated by the two major political parties in the country: both parties claim that the legitimacy that will flow from an internationally accepted election will prove to be the panacea that will end the crisis and resolve the deep-seated problems — political, economic, and social — that afflict Zimbabwe.

We reject this misguided optimism as we have since 2016.

The hope about elections has been fostered by the surprising result in the Zambian election and the re-emergence of a popular opposition, the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC). Whilst it is heartening to see this, it is evident that this merely deepens the political polarisation in the country, and a country that is the most politically polarised in Africa. This polarisation is reflected in the total absence of political trust by the citizens in political parties, the government, and the state.

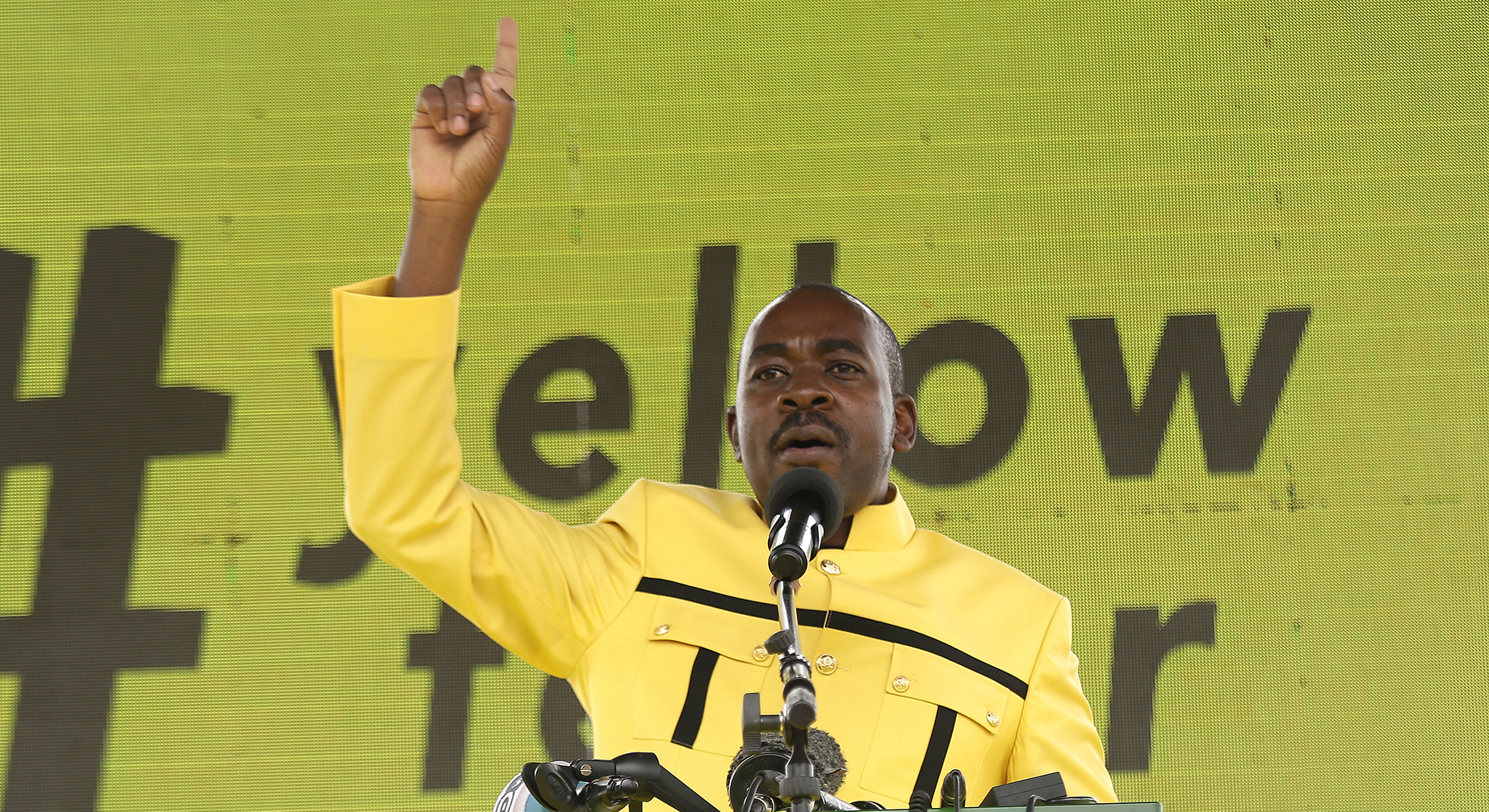

Citizens Coalitions for Change (CCC) leader Nelson Chamisa speaks during his campaign rally in the township of Highfields, Harare, Zimbabwe, 20 February 2022. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Aaron Ufumeli)

The hope is also given new energy by the results of the by-elections and the confirmation that, despite all the manoeuvring to destroy the Chamisa faction of the MDC, the new party, the Citizens Coalition for Change (CCC) restores the polarisation of two big parties in Zimbabwean politics. Zanu-PF will have to face the fact that no GNU or political settlement can take place without the CCC, and that buying time to resolve its internal chaos has not changed the political reality in Zimbabwe.

The low poll, which is usually the case, also demonstrates the total absence of political trust in the state, the government, and political parties.

Citizens in Zimbabwe trust only NGOs and religious leaders, and too often the vote for the opposition is a mixture of support as well as a rejection of Zanu-PF, with the opposition seen as the lesser of two evils. The Afrobarometer survey in 2021 found that nearly half (49.8%) of Zimbabweans would not vote, and didn’t know, or would not say who they would vote for. Mostly this is argued to be due to the “fear factor”, but it is also due to the total lack of political trust. However, it is the case that many who are reticent hide their affiliation with the opposition.

This seems strongly plausible with the complete failure of governments since 2000 to address the deepening poverty that afflicts most Zimbabweans, to stem the vast corruption that is documented nearly every week, the slow but steady collapse of the state and its ability to deliver public goods and services to the population, and the inevitable violence that accompanies elections.

People gather around a fire on the street during a protest against polling results in Harare, Zimbabwe, 1 August 2018 (issued 02 August 2018). The day saw protests turn violent when police fired rubber bullets and teargas, before the army was called in and began firing live rounds. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yeshiel Panchia)

We reject this forlorn hope about the curative power of elections because the impediment to such a solution remains the securocrat state, the deep structure that controls civilian affairs in Zimbabwe.

Thus, before any thought about the outcome of elections, there must be frank discussion about what actual conditions the election 2023 must achieve if there is to be any sense that the election is an acceptable basis for examining reforms. The Constitution states explicitly what is expected in an election in Section 155 (1):

“peaceful, free, and fair; conducted by secret ballot; based on universal adult suffrage and equality of votes; and free from violence and other electoral malpractices.”

This is the basic litmus test for any election in Zimbabwe, and for these conditions to be met, the election must be able to pass a straightforward audit, covering the transparency of several crucial processes, and these conditions must be observably present before voting takes place. Such an audit is already in progress with the first discussion already raising red flags.

Pre-auditing the 2023 elections

A very useful framework for conducting a pre-election audit was provided by Phillan Zamchiya at a recent policy dialogue on elections. Part of a series being mounted by the Sapes Trust and the Research and Advocacy Unit (RAU), this framework combines the technical matters referred to above with the political economy context.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Simply, the framework proposes five pillars essential to a bona fide election:

- Information: This refers to the ability of citizens to obtain all kinds of information, and not merely the openness of the media to reflecting the multiple perspectives of the electoral constants. It also refers to the ability of citizens to engage with politicians and attend meetings and rallies without fear and constraint.

- Inclusion: This refers to the notion that elections are about free and equal participation in the electoral process. There are difficulties in registering as voters, with indications that the numbers registering are low. This is partly due to the perception that elections are never free and fair, and the difficulty in obtaining identity documents, the prerequisite for registering. The conditions for Inclusion are absent.

- Insulation: This refers to both the ability to freely participate in elections and to freely vote, which have been problems in most elections in the past two decades. It refers also to the ability to be free from intimidation and violence, and for all forms of treating to be absent. Clearly, with the imprisonment of opposition leaders, the banning of political meetings, and the escalating political violence, the conditions for Insulation remain seriously flawed.

- Integrity refers to the impartiality and accountability of the election management body, ZEC. There are many signs that ZEC is not impartial as is required by the Constitution, including the significant numbers of military personnel working in the institution. However, it is not merely ZEC that must be impartial in the electoral process: all government agencies must be impartial, and this is doubtful in the aftermath of the coup. The Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) and the Zimbabwe National Army (ZNA) must be firmly under civilian control and politically impartial as required by the Constitution. The available evidence is that Integrity is wholly absent in Zimbabwe and will not be present until the coup is cured.

- Irreversibility refers to several things. Firstly, that there is no reversing or tampering with results: the count and the outcome must reflect the will of the people. Secondly, it refers to the acceptance of the results by the loser. Irreversibility has been a problem in every election since 2000, with the courts a major obstacle in resolving election disputes. We should not forget 2008 when the MDC-T won the parliamentary and presidential elections, but Zanu-PF would not concede nor would Africa force them to do so: the consequence was a bloody run-off for which Africa should accept some of the blame. The available evidence is that Irreversibility is by no means assured for the coming elections.

Elections in the current state of the nation

There must be some reasonable conjecture, however, about whether Zimbabwe will even reach an election next year without a national crisis taking place. The deepening crisis within Zanu-PF ahead of the elective congress later this year suggests that the leadership conflict is far from settled, and may force the securocrat state to consider other options.

The economy may force other options as well: the rampant and rising hyperinflation seem beyond the control of the government, and, despite the rhetoric, the living conditions of virtually all citizens are worsening weekly, if not daily. Mozambique and Sri Lanka are instructive here. Furthermore, the country is yet to feel the full effects of the international crisis.

None of these factors are propitious for the holding of elections.

Zanu-PF President Emmerson Mnangagwa arrives at the National Stadium, Harare, Zimbabwe, 28 July 2018. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yeshiel Panchia)

Conclusions

We stated at the outset that it was extremely doubtful that any election in Zimbabwe could resolve the crisis. For this reason, we have posed what can be seen as the minimum conditions for an election to meet acceptable standards, whether those of SADC or the AU.

Given the history of elections in Zimbabwe in the past two decades, it is obvious that there should be considerable misgivings that this election could be any different, and especially in the light of the statements by Zanu-PF that they will not accept loss and feel entitled to rule forever. This cannot be seen as mere rhetoric.

Furthermore, the reforms needed to the state have not happened despite all the promises of a “second republic” and a “new dispensation”. Multiple reforms are needed before there is any prospect that any election can create a legitimate government.

However, we are locked into an election, with both major parties claiming that they will be victorious, and hence nothing will happen until the election is over: all regional and international factors have no choice except to sit and wait for the outcome. If this election can meet the standards we have outlined above, there may be a faint hope that 2023 will see a government in place that all can accept as legitimate, but our bet is that even these minimum standards cannot and will not be achieved. Then, the only solution will be political settlement, national dialogue, and a National Transitional Authority.DM/MC

Ibbo Mandaza and Tony Reeler are Co-Conveners of the Platform for Concerned Citizens (PCC).

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.