BOOK EXCERPT

Farmworkers have a claim to the stolen land of their ancestors as reparation for generations of exploited labour

Farmworkers’ land aspirations are greater than producing food for themselves and their families; they see themselves as farmers in their own right, as workers of the land, as producers of food and as farmers of livestock, and they strongly believe in their ability to contribute substantially to domestic and continental markets. An effective land redistribution programme must support their ambition.

Growing up on a farm in Nyarha, in the Eastern Cape, I had a beautiful childhood. There was the innocence of childhood, just being a little girl running freely and playing with oonopopi (“dolls”), iraysisi (“racing”), undize (“hide and seek”), upuca (“the stones game”), and ugqaphsi (“jumping rope”). The sense of community, freedom and interdependence in communal living was another joy.

My parents could send me to a neighbouring homestead without any fear for my safety. My mother would often send me to the neighbour’s house to ask for igaqa le beef stock (“a cube of beef stock”) to season our food if she didn’t have any, or intwana ye swekile (“some sugar”) if she ran out.

The only time when I felt the absence of that freedom and the sense of belonging begin to dwindle was at the sight of the white owner of the farm on which my parents laboured. Instantly, I became overwhelmed by a great fear.

The fear was both a learned and taught behaviour; we were taught that it was a form of respect. While taking instructions from the farmer, my grandfather would be deferential, bowing his head to avoid eye contact. When my father heard the sound of the farmer’s motorcycle approaching, he would quickly hide his beer.

As a child, I found it peculiar when my father used to tell me that all of the vast farmland around eNyarha belonged to white people. None of the Black people had any land.

As an adult, I was enraged to learn that five generations of my family had worked for the same family, but we had no claim to that land whatsoever. I questioned why my family’s decades of labour bore fruit only for the wealthy white landowners and their descendants. I could not reconcile the story of five generations of hard labour with the life we were living: a life of poverty.

Farmworkers relate to the land with a sense of belonging and cultural heritage, often referring to it as umhlaba wookhokho bethu (“the land of our ancestors”). This phrase has multiple meanings in the context of farming communities. Not only do they think of the land of their ancestors through a historical lens; they also conceive of it as an unresolved question of injustice, understanding it to be deeply rooted in history and in generations of exploitation by white farm owners — a history that continues to the present day.

Farmworkers see the land as having been stolen from their forefathers through the process of colonial dispossession and deception that advanced the development of capitalism. This not only led to the loss of land and livestock, but also a disruption of pre-colonial African conceptions of land relations and land use. The understanding of the land as a commons — that it can be held and worked communally — was largely destroyed.

Though the Freedom Charter promises that “the land shall be shared among those who work it”, and section 25 (5) of the Constitution promises equitable access to land, these promises have yet to be fulfilled.

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

Several generations of landless farmworker families have used their labour in service of the productivity and maintenance of farms across the country. In the process, they have contributed immensely to the generational wealth of farm owners. Farmworkers tie this process to the labour struggles of their forefathers; long-term generational labour on farms should be considered a sufficient reason not only to justify farmworkers’ tenure, but also to claim land ownership.

Baw’uMkwayi, a retired farmworker on another livestock farm in Nyarha, in the Eastern Cape, told me that:

‘all of them [my family] worked on the farm… I also worked there for 20 years… [and] my wife also worked on that farm… for 20 years in the kitchen at the farm owner’s compound. When we left, she too got nothing; she left empty handed’.

Ryno Filander, president of the CSAAWU, a farmworker’s union in the Western Cape, said that he, his father and his mother all work on the same wine farm in Langeberg. He explores two parallels on the farm: the multigenerational wealth and power of farm owners and the multigenerational poverty and powerlessness of farmworkers.

“If you have land, you have power,” he says.

The other problem, Ryno explains, is the “dop system”. With the dop system, employers pay their employees with cheap wine, or dop. Though the dop system was outlawed in South Africa in the 1960s, in the late 1990s researchers estimated that anywhere from 2% to 20% of wages in the Western Cape were still being issued in alcohol.

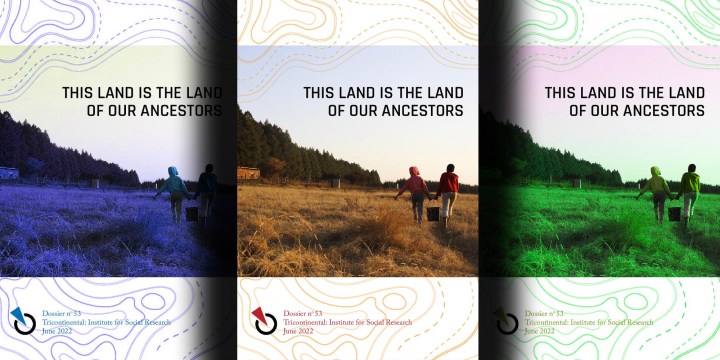

An effective land redistribution programme is required for farmworkers to realise their land rights and aspirations. (Photo: Reuters / Siphiwe Sibeko)

Grave matters

Farms have also become places of great spiritual significance for farmworkers whose ancestors were buried on that land. For farmworkers, their ancestors’ graves are in many instances proof of the intimacy between work and life on the farms.

The concepts of home and belonging are also influenced by the ancestral connection between the living kunye nezinyanya (“and ancestors”). This is one of the main reasons families live on farms for years despite exploitation and abuse.

As MaNkomo, a farmworker I spoke to in Mooi River, KwaZulu-Natal, explained, “We don’t want to leave these farms because our parents and grandparents are buried here”.

Farmworkers and farm dwellers see ancestral graves as both proof of labour and a political claim — that scores of people buried on farms were once labour tenants and exploited workers who ensured the farm’s flourishing. These graves are a testimony to the lives of those who bore the brunt of racial capitalism.

Currently, land governance does not take cultural aspects and generational labour as a model for land redistribution into consideration and continues to reproduce pain and trauma for the landless. This contributes to the dismal failure of the land reform programme that is currently being implemented by the state.

Despite the fact that farmworkers in South Africa — and around the world — provide food for society, they are one of the groups most vulnerable to food insecurity. What we eat, drink and wear is all thanks to farmworkers. Though their skills and expertise are crucial to the economy, their labour continues to be devalued. Seasonal farmworkers (usually women), who are often employed for only half the year, regularly face the challenge of job insecurity, given that they do not have access to their own land to produce food year-round.

Climate change has also rendered farming an increasingly precarious field, mainly for frontline and low-income communities around the world.

One of the main critiques presented to argue against the redistribution of land is the dangerous myth that it will negatively affect food security. This myth not only disregards the fact that billions of people around the world already experience food insecurity, but also relies on large-scale production and manufacturing under capitalism as the only path forward.

Rather than centring a concern to guarantee food security for all, capitalist paranoia fixates on its fear that redistributing land will disrupt profit revenues generated by large-scale farming and food production. While some farmworkers, mainly the elderly, are asking for the recognition of peasant landholdings, where small landholders survive from and produce on the land, ukulima (“crop farming”) and ukufuya (“animal husbandry”) are not limited to familial subsistence.

Generally, farmworkers are critical of the myth that white farmers are the only ones capable of farming with superior technology and are the only efficient producers, while Black farmers only farm for subsistence and contribute minimally to the economy. Farmworkers’ land aspirations are greater than producing food for themselves and their families; they see themselves as farmers in their own right, as workers of the land, as producers of food, and as farmers of livestock, and they strongly believe in their ability to contribute substantially to domestic and continental markets. An effective land redistribution programme must support their ambition.

Descendants of the forgotten workers from centuries past call for reparation. A land redistribution discussion which deliberately ignores African modes of being and relationality to land upholds the colonial project and portends dehumanising exclusion. Any land redistribution programme which ignores these claims is insufficient.

Loo ngumhlaba wookhokho bethu! This is the land of our ancestors! Land to those who work it; it is high time that those who work the land get to own the land. DM/MC

Yvonne Busisiwe Phyllis is the co-director of The Forge, a space for public engagement in Braamfontein, Johannesburg. She is also the author of This Land Is the Land of Our Ancestors, recently published by Tricontinental: Institute for research, a global South thinktank.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I see where you are coming from, but I also see where you are going with this. Its called Zimbabwe, once known as the bread basket of Africa. Once the descendants of the forgotten workers get reparation, Unlike the Zimbabweans who keep moving South in droves to escape from themselves, South Africans have nowhere to go.