EDUCATION OP-ED

Schools bill is no betrayal, it’s a belated move to update the law

Rather than introducing something new, the Basic Education Laws Amendment Bill is just bringing the law in alignment with what cases have already confirmed: the role of school governing bodies is critical, but the State has important and final oversight responsibility to ensure equity.

“A breach of the 1994 settlement”, an attempt to “hijack” functioning schools and “draconian”. These are just some of the ways that interested groups such as Afriforum, Solidariteit and the Democratic Alliance have referred to changes related to the powers of school governing bodies (SGBs), contained in the Basic Education Laws Amendment Bill (Bela), currently being considered by Parliament. In contrast, Equal Education (EE) and the Equal Education Law Centre (EELC) welcome these changes in our joint submission on the Bill.

At the heart of the controversy around Bela, are the changes it proposes in relation to greater oversight over language policies by provincial education departments, requiring schools to submit admissions policies to education departments for review, and clarifying that the final decision about the placement of a learner lies with the provincial department.

It is already well known that SGB powers are controversial — since the promulgation of the South African Schools Act (Sasa) in 1996, a striking feature of the education landscape has been the numerous court cases around the powers of SGBs versus those of the State. Central to many of these cases has been the question: where does the final decision-making power lie? Rather than introducing something new, Bela is just bringing the law in alignment with what these cases have already confirmed: the role of SGBs is critical, but the State has an important and final oversight responsibility to ensure equity.

Equal Education members march to the Department of Basic Education’s offices on June 17, 2013 in Pretoria, South Africa. The demanded that Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga publishes minimum norms and standards for school infrastructure. Equal Education is a movement of pupils, parents, teachers and community members working for quality and equality in education. (Photo: Gallo Images / Foto24 / Alet Pretorius)

To fully understand the debate — and what it has to do with the 1994 negotiated settlement — we must go much further back, to before South Africa’s democratic transition.

The debate around school governance featured prominently during the transition because education was highly important for both the liberation movement and the apartheid government. As former education bureaucrat Ken Hartshorne pointed out, “the domain of education was not to be surrendered easily and was hotly contested by the state: it was to prove to be one of the last bastions of apartheid”.

At the time, both the National Party and opposition forces (loosely termed “the liberation movement”) were in favour of greater involvement of school communities and parents in decisions affecting schools, but their positions were of course informed by competing political ideals.

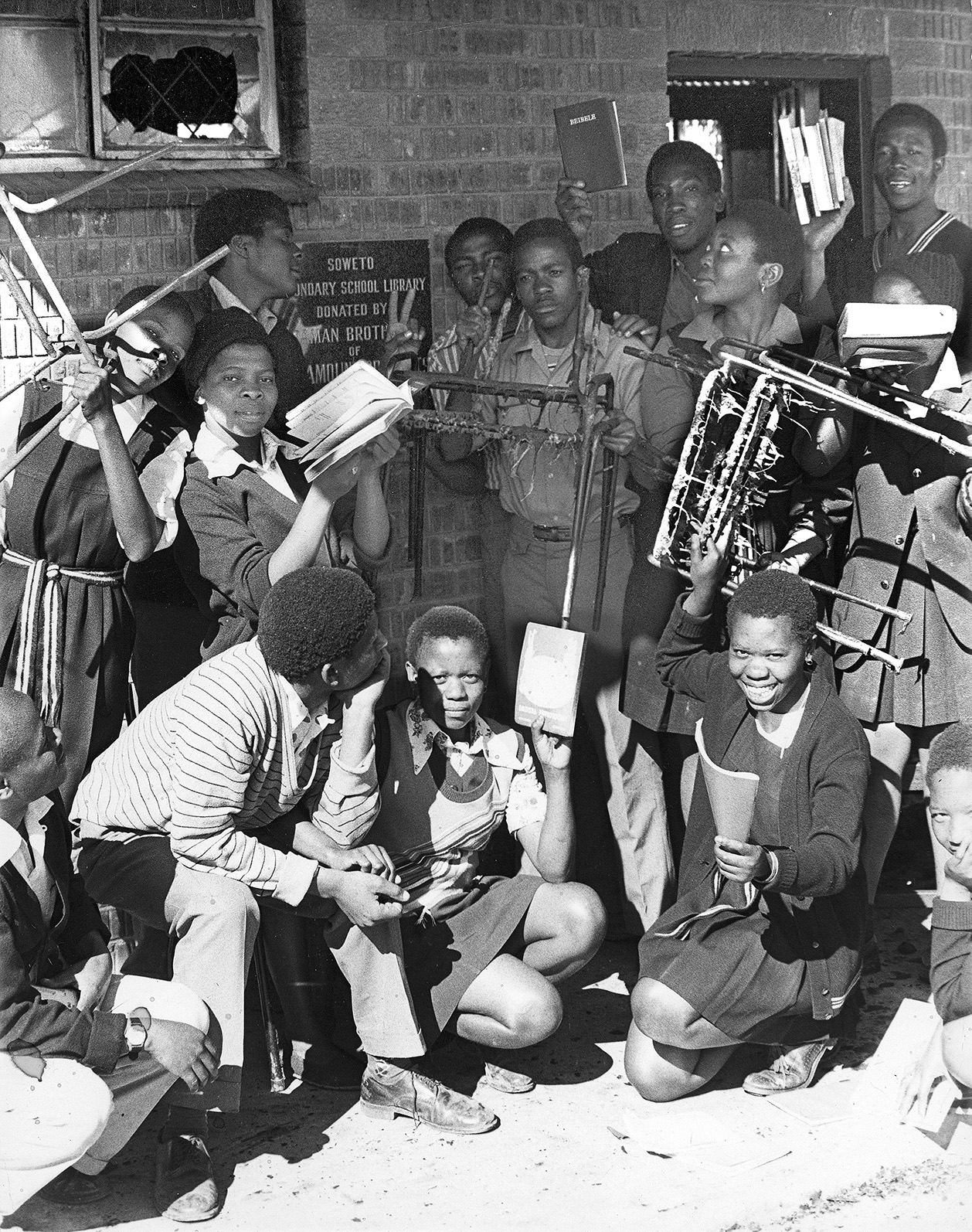

Students standing in front of their burnt school during the June 1967 uprising in Soweto, Gauteng. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

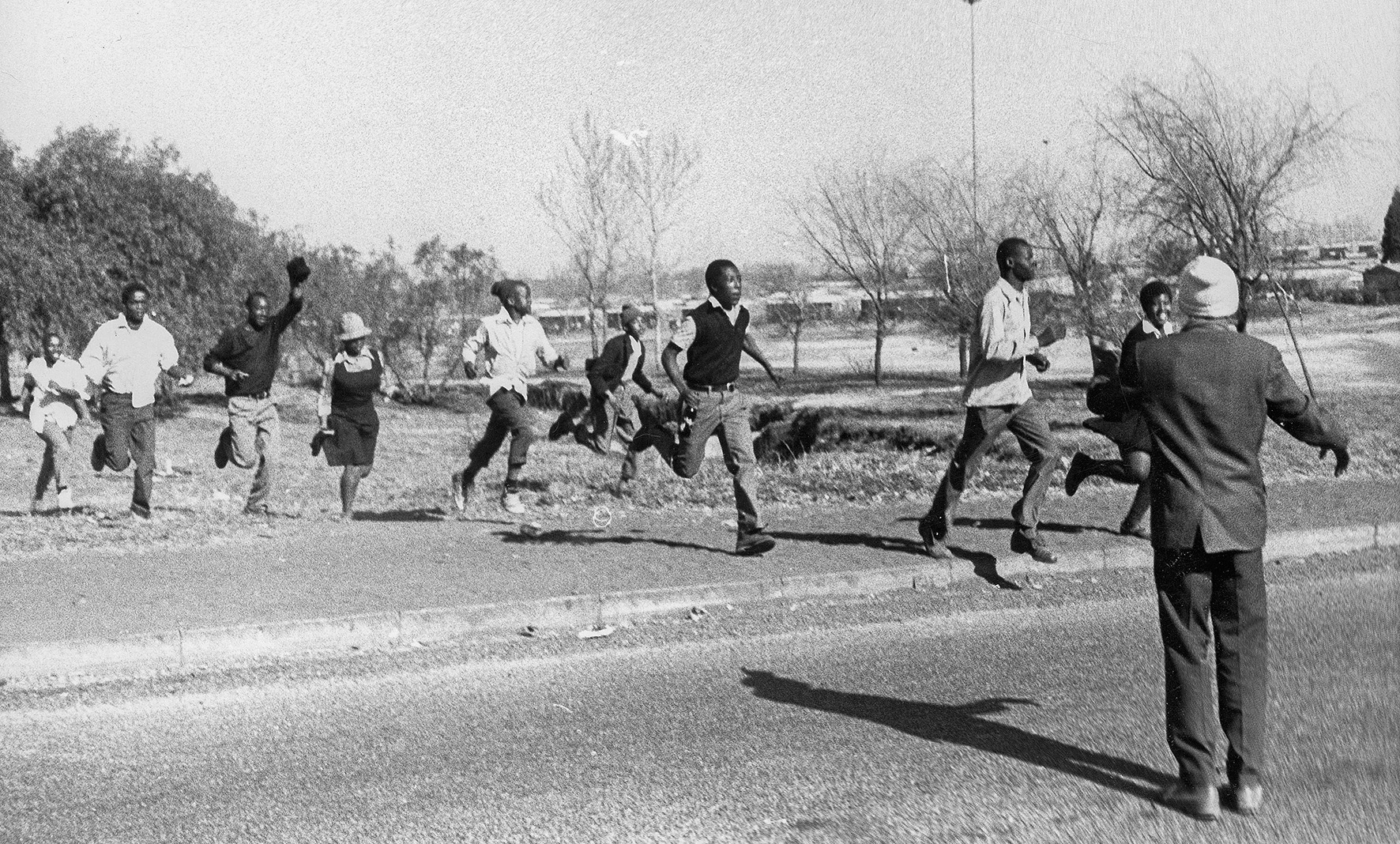

The youth of 1976 solidified education as key site of struggle against the apartheid regime. In the aftermath of the Soweto uprising, the liberation movement called for parent and community participation in school governance, as a response to the apartheid government’s autocratic decision-making about schools. However, policy proposals coming from the liberation movement also emphasised the importance of structures to upskill SGBs in all schools and a strong central State to ensure redress and equality.

For the National Party, placing as much decision-making power as possible — and the ability to raise funds — at the school level, would largely isolate former white schools from significant changes after the transition. While in policy documents the Nats had learnt to speak the language of ‘justice’ and ‘equality’, it made almost no proposals on redress.

Students protesting during the June 1967 uprising in Soweto, Gauteng. (Photo: Gallo Images / Rapport archives)

In 1992, shortly before the transition to democracy and while negotiations with the African National Congress (ANC) were ongoing, the apartheid government converted most white public schools (a small minority of schools) to what it referred to as Model C schools (where the commonly used term ‘former-Model C schools’ comes from). Control of these so-called ‘State-aided’ schools was handed to governing bodies elected by parents, who received a government subsidy for staff salaries but had to raise all school capital costs through fundraising activities. Parents gained control over admission and language policies and, in an extraordinary step, public school property was transferred to governing bodies free of charge (following the transition, these properties had to be transferred back to the State).

Educationist Pam Christie aptly refers to these shifts as “transition tricks”, a process through which the apartheid government at the last minute before the transition, essentially turned South Africa’s most privileged schools into semi-independent schools. So powerful was this push to secure power at the SGB level, that South Africa’s Interim Constitution specifically mentioned SGBs, noting that no changes could be made to their powers and functions “unless an agreement resulting from bona fide negotiation has been reached with such bodies”!

These arrangements as well as the pressure to reach a negotiated settlement, shaped negotiations on SGB powers. In the end, the version of SGBs captured in SASA resembled more closely the National Party’s ideals, left the State with a weakened role in schools and watered down clauses on support for SGBs. Blade Nzimande, who was chairperson of the education portfolio committee in Parliament when Sasa was drafted, explains about its finalisation:

“Remember these were the days of the Government of National Unity. It was important at that time to secure the transition. The situation was explosive and we were on the brink of civil war. Our policies were therefore crafted in a context where ensuring a smooth transition was as important as developing progressive policies for social transformation.”

South African Communist Party Secretary General Blade Nzimande. (Photo: Gallo Images / City Press / Tebogo Letsie)

The arrangements contained in the original version of Sasa, therefore, came about in a particular time and context, with very specific dynamics playing into decisions made at the time. Rather than signifying a betrayal of the 1994 settlement, as some would have us believe, it is to be expected that in the almost thirty years since then, some rethinking of these arrangements is necessary.

Moreover, the exclusionary practices by some SGBs provide further impetus to do just that. There are numerous examples where language policies have been used as a proxy for racist practices and actions, specifically by Afrikaans single medium schools. The Federation of Governing Bodies of South African Schools (Fedsas) has acknowledged, in litigation initiated by it, that some schools have used their language policies as a “mechanism for screening applications in a manner that suggests that the screening occurs with racist intent”.

In the 2009 case about language of instruction at Ermelo High School, former Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke berated the school’s SGB for arguing “that it is entitled to determine a language policy having regard only to the interests of its learners and of the school in disregard of the interest of the community in which the school is located and the needs of other learners”.

Former deputy chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke. (Photo: Gallo Images / City Press / Tebogo Letsie)

Exclusionary practices continue. Through its law clinic, the EELC regularly deals with cases where language and admissions policies are being used to unfairly discriminate against learners.

On the other hand, there is a danger in assuming that the State will always act with benevolent intent. Governing parties and officials have their own ambitions and incentives which may not necessarily align with the best interest of learners or be in pursuit of equity. In a number of cases relating to language and admissions, the actions of provincial education departments were overturned due to unfair administrative practices.

What’s more, SGBs have a crucial role to play in schools, and we must remember they are a key feature of all public schools, not just the wealthy ones. SGBs understand the particular context of a school much better than most government officials, they bring community and parent perspectives into decisions and often have to lead where provincial education departments are absent or lack capacity. A previous version of the Bela Bill, published in 2017, proposed that SGBs only be involved in entry-level teacher appointments, but this has been abandoned in the 2022 version. EE and the EELC opposed the original amendment, because it undermined the important input by SGBs in key decisions related to the school. Our proposal in 2017, that SGBs must be consulted before a learner is placed in a school, and that the SGB must be given the opportunity to appeal, have been included in the 2022 version of the Bill.

As our courts have confirmed, schools must serve the public good, not only the interests of the individuals in their school. While SGBs continue to have power — they still formulate admissions and language policies — they must be held to their public duty by the State. And the State must use its power to equip SGBs and ensure that resources within the public education system are equitably distributed. It is in the interplay and collaboration between SGBs and the State, that there seems to be the greatest potential for fairness and justice. DM/MC

McFarlane is Equal Education’s Senior Manager for Research and Development.

This article is a longer version of an article originally published in the Sunday Times.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.