COSMIC POLITICS

Requiem for international cooperation in space: Is the ISS another casualty of Putin’s invasion?

Russia has decided that since it isn’t winning the war in Ukraine that it launched in February, the right response is to announce the end of its participation in the International Space Station, and go off and build its own instead.

Russia has made an unexpected announcement that, by 2024 (although now being muddied a bit to perhaps a withdrawal date of 2028, due to yet further statements from Russia), it will cease participation in the International Space Station (ISS).

Presumably, this represents yet another casualty of Russia’s war against Ukraine, and the background of efforts by many nations to come to the aid of the beleaguered Ukrainians in their struggle against the invasion.

If and when such a development happens, it would be a serious brake on efforts to forge a close, broad-based, transnational space exploration effort. Instead, such a decision would mean space exploration would, yet again, increasingly take on the nationalist colouration many had hoped, despite Earthly behaviour, could be banished in space exploration, if not on the surface of the planet.

Russian President Vladimir Putin (left) at a meeting with Roscosmos Director-General Yuri Borisov (right) at the Kremlin in Moscow on 26 July 2022. Borisov announced Russia’s plans to withdraw from the ISS project after 2024 and begin the formation of the Russian Orbital Station. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Mikhail Klimentyev / Kremlin Pool / Sputnik)

According to National Public Radio, drawing on the Associated Press, “Russia will pull out of the International Space Station after 2024 and focus on building its own orbiting outpost, the country’s new space chief said Tuesday amid high tensions between Moscow and the West over the fighting in Ukraine.

Yuri Borisov, appointed this month to lead the state space agency, Roscosmos, said during a meeting with President Vladimir Putin that Russia will fulfill its obligations to its partners before it leaves… ‘The decision to leave the station after 2024 has been made,’ Borisov said, adding: ‘I think that by that time, we will start forming a Russian orbiting station.’ ”

Cynics (and some hard-headed realists too) could be heard muttering that such a plan could only be carried out — given the enormous costs involved in creating its own space station — after Russia gives up its quixotic delusions about trying to conquer and pacify neighbouring Ukraine.

Such an effort would also presumably require managing to hold on to its billions of dollars now sitting in foreign banks, but being hunted down by those who see that hoard as a possible way to access funds for reparations after all the damage inflicted upon its neighbour. Moreover, it would also mean Russia will have to figure out ways to procure all the hi-tech, imported technology that would be needed for that effort.

ISS partnership

The international partners who operate the ISS (but apparently will not include Russia in future) have repeatedly said they want to keep the current space station in orbit and on the job until 2030, even after current international arrangements for its operations end in two years. The ISS is a joint project of the space agencies of Russia, the US, Europe, Japan and Canada.

The initial section of the ISS was placed into orbit nearly a quarter of a century ago, and the ISS has been continuously occupied for almost 22 years. Its multinational crews have carried out scientific research in zero gravity and tested potential new equipment for future, more distant space journeys.

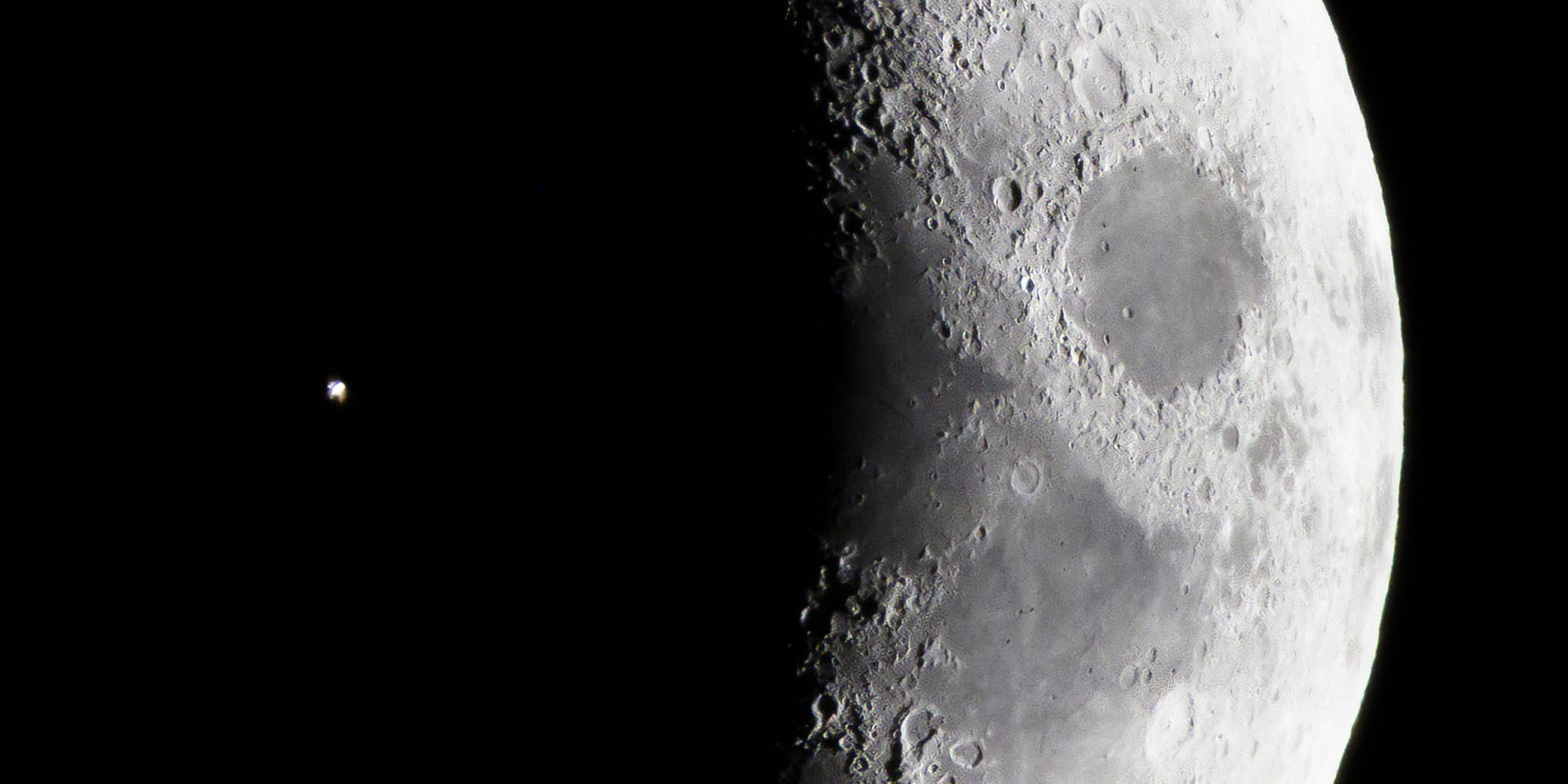

The International Space Station flies by the crescent moon as seen from Washington, DC on 8 December 2021. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Jim Lo Scalzo)

Over the years, the ISS has usually been staffed by a seven-person crew, most of whom usually spend several months at a time in orbit on the facility. At this moment, its crew includes three Russians, three Americans and an Italian, as the ISS completes its orbits about 350km above the surface of the Earth.

The ISS is about as long as a football pitch and consists of two sections. One is run by Russia and the other by the US, with other nations. In the immediate aftermath of the surprise announcement by Russia, it remains unclear what would be required to keep the Russian section running properly and safely once Moscow pulls out.

It is obviously not simply a matter of periodically checking on some dials and digital readouts, and punching a few buttons or manipulating a bunch of toggle switches and knobs, or just adding a few more cables and hoses to keep all the machinery ticking over, supplied with power and venting away any noxious gases. The ISS is not, obviously, a facility that can undergo a bit of spring cleaning to make it all shipshape and sparkling like new.

Sanctions speculation

Virtually the moment the Russian government made its announcement, speculation was rife that this was one more Russian manoeuvre to extract some relief from Western sanctions now in place as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In fact, and lending credence to that theory, the previous Russian space programme director, Dmitry Rogozin, had said just a month earlier that Russia could take part in negotiations about a possible extension of the station’s operations, but only if the US lifted its sanctions on Russian space industries.

For years, after the end of the US’s re-launchable/reusable space shuttle programme, crew travel to and from the ISS had been dependent on Russia’s workhorse Soyuz fleet. However, now that Elon Musk’s SpaceX company has taken over transporting Nasa astronauts to and from the space station, the Russian space agency has lost one of its major sources of income, as those transportation tickets were not cheap. In fact, for years, Nasa had been paying tens of millions of dollars per seat for rides to and from the station aboard Russian rockets, but that lucrative service is now at an end with the advent of Space X’s more cost-efficient fleet of reusable craft.

Members of an International Space Station expedition, Nasa astronaut Christopher Cassidy (left), Roscosmos cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin (centre) and Ivan Vagner (right) attend their final exams at the Russian cosmonaut training centre in Star City outside Moscow, Russia, 12 March 2019. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yuri Kochetkov)

A Soyuz MS-13 spacecraft with members of the International Space Station (ISS) expedition 60/61, Nasa astronaut Andrew Morgan, Roscosmos cosmonaut Alexander Skvortsov and ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano lifts off from the launch pad at the Russian-leased Baikonur cosmodrome, Kazakhstan on 20 July 2019. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Yuri Kochetkov)

Up until this announcement about terminating its participation in the ISS, despite the Ukrainian invasion, Nasa and Roscosmos had, according to the Associated Press, “struck a deal earlier this month for astronauts to continue riding Russian rockets and for Russian cosmonauts to catch lifts to the space station with SpaceX beginning this fall. But the flights will involve no exchange of money. The agreement ensures that the space station will always have at least one American and one Russian on board to keep both sides of the outpost running smoothly, according to NASA and Russian officials”. But, apparently, not after 2024, or 2028, depending on which duelling media announcement from Russia one credits.

‘Wiggle room’

Reuters (and Russia) added some further complexities and confusions to this saga after the initial reports, noting that “On Tuesday (26 July), Yuri Borisov, the new head of Russia’s space agency Roscosmos, announced that the nation planned to leave the ISS consortium ‘after 2024’.

“[But] that statement contains quite a bit of wiggle room, and it appears that Russia is going to take advantage of it. The nation intends to remain an ISS partner at least until its own space station is up and running, a milestone that’s not expected until 2028 at the earliest,” Reuters reported on Wednesday. Reuters cited Nasa human spaceflight chief Kathy Lueders, who said she spoke to Russian space officials on Tuesday after Borisov’s announcement.

“‘We’re not getting any indication at any working level that anything’s changed,’” Lueders told Reuters. She described the human spaceflight relationship between Nasa and Roscosmos as “business as usual”.

Members of the International Space Station expedition 61/62, UAE astronaut Hazza Al Mansouri , Roscosmos cosmonaut Oleg Skripochka and Nasa astronaut Jessica Meir seen on screens during their final exams at the Russian cosmonaut training centre in Star City outside Moscow, Russia, 30 August 2019. (Photo: EPA-EFE / Maxim Shipenkov)

“Many of Russia’s other space partnerships, however, have fractured or dissolved recently, a result of the nation’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine. Russian rocket engines are no longer sold to American companies, for example, and Russian-built Soyuz rockets have stopped flying out of Europe’s Spaceport in French Guiana.”

Years earlier, at the height of the Cold War in 1975, American Apollo and Soviet Soyuz spacecraft had docked together in orbit in the first crewed international space mission, boosting efforts to improve US-Soviet relations, even as so many other nuclear-tipped rockets were targeted on the respective nations’ cities and military facilities.

More recently, Nasa has been working with American companies on plans to create privately constructed and operated space stations (presumably with internationally staffed crews) that would eventually replace the ISS when it finally reaches its sell-by date, and Nasa hopes those facilities will become operational by the end of the current decade.

Shifting impulses

Importantly, space exploration has, virtually from its beginnings, been the subject of twin impulses — one an international dream of uniting humanity in the great journey, and the other a more nationalist strand, often tied closely to defence and security efforts. Back in the late 1950s, when space exploration first began with the launch of the then Soviet Union’s Sputnik satellite, space quickly moved from being the subject of science fiction writers and on to the headlines of newspapers.

Given the circumstances of the Cold War, for both nations, nearly all of the effort quickly shifted from being a glorious effort by humanity on to a two-country race comprising discrete stages where “trophies” could and would be claimed after each milestone event, proving the superiority of one political-economic over the other.

Which nation would manage to launch the first satellite, to put the first man in orbit, to send the first manned flight around the Moon, and then, finally, triumphantly, to send the first men to land on the lunar surface all became world-shaking events. In America, in the Soviet Union, around the world, success in this newly proclaimed space race was viewed by many as a tangible measuring rod of the relative competitiveness and capabilities in the great “capitalism versus communism” debate. (While the American manned astronaut programmes were run by a civilian agency — Nasa — all members of the astronaut corps were military test pilot veterans.)

Soviet successes

For Americans, the early successes of Soviet launches of unmanned satellites, then Laika the dog (sadly on a one-way voyage to fame), and then followed by Yuri Gagarin in that first launch into orbital space around the Earth simply compounded panic on the part of Americans about losing their competitiveness vis-a-vis the Soviets.

The popular cry was that the nation had lost its way, producing Cadillacs with massive tail fins, automatic dishwashers and washing machines instead of the kinds of missiles and rockets (and a 50 megaton nuclear bomb as the Soviets did) to assure the country’s ascendancy in space. That was coupled with an apparent ability by the Soviets to blast their unstoppable, deadly rockets down to Earth — ie, the United States — from the heavens.

Moon landings, Voyager odyssey

The American response took time to lumber into position, but, by 1969, it had “won” a key leg of the space race as it began delivering two-man crews to the surface of the Moon, among other success stories that included fantastic unmanned planetary explorations (and their astonishing photographic results), as well as bringing on the revolutionary age of satellite communications, navigation and weather forecasting.

But the first Apollo lunar lander also bore a plaque that read, “We came in peace for all mankind”, giving symbolic service to the idea that Nasa’s space exploration was being conducted on behalf of the entire population of Earth, rather than for the more parochial benefit of the Americans.

It has been this larger, competing idea — the broad planet-wide view rather than one nation besting another in space in a Herculean struggle — that was also expressed through the contents of the gold-plated disc attached to the exteriors of the Voyager spacecraft for the time when they might eventually encounter an alien civilisation, many light years beyond our own solar system.

The creation of that disc, by a team spearheaded by the then-young, exo-planetary astronomer Carl Sagan, had deliberately produced a recording containing images representing the faces and works of all of humankind, as well as the planet’s other animal and plant species, rather than it being a bit of chauvinist cheerleading for Nasa and America. Of course, Star Trek fans already understood this impulse well, what with the space ships being crewed by a mixture of Earthlings and aliens alike, and the Terran parts of the crew including representatives of many of the planet’s former nations.

Earthly frontiers

In fact, the idea of space exploration as a global endeavour also has some deep roots. Pioneers and theoreticians like America’s Robert Goddard and Russia’s Constantine Tsiolkovsky had both seen rocketry and space exploration as the task and opportunity of a common humanity. The assumptions of most science fiction writers, too, from Jules Verne onward, have been that space was a place beyond those narrow, earthly frontiers.

But the advent of practical military rockets like the V-1 and V-2 under engineers and scientists such as Germany’s Werner von Braun proved the harsh military utility of rockets. Then, in the aftermath of World War 2, the Americans and Soviets engaged in frantic efforts to find and then recruit the German rocket teams and their plans, machinery and projectiles for their own national projects.

Sadly, even though the impetus for the ISS was for it to be a broad, multinational effort including crews from many nations, the Russian invasion of Ukraine (plus the loss of revenue as a result of the Americans’ switch from the Russian rocket to Elon Musk’s Dragon SpaceX vehicles) may have wrecked an admirable experiment in international cooperation in the exploration of space.

Space may no longer be the final frontier for a common humanity, but perhaps it is now, again, being reinforced by those earthly frontiers instead. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.