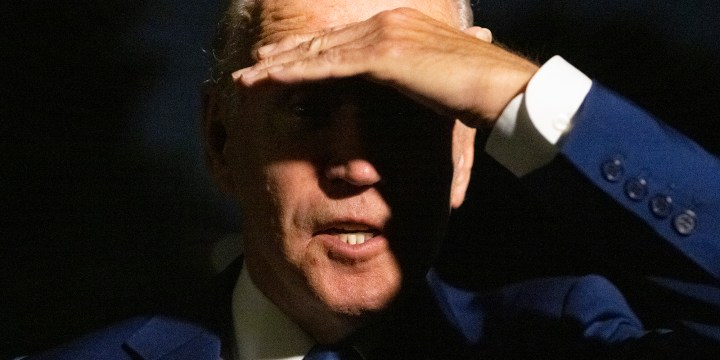

BIDEN IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Biden’s metaphorical Middle East minefield – Mind your step!

President Biden’s just-completed trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel (and the West Bank) has not delivered concrete outcomes – at least not yet – but the issues for the trip still remain.

It is ironic that many of the complexities, ambiguities, challenges, and possibilities incorporated in US President Joe Biden’s Middle East trip stem from a collection of decisions and statements made by his predecessor.

Of course, other factors are now baked into the tangled historical circumstances of the region, or – importantly – a result of new power relationships evolving in the region. Naturally, too, that collection of issues has American domestic angles as well, like the continuing repercussions from the deaths of two journalists with US connections (and American citizenship in the case of one of them). Add the effects of the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine, and it would have been a very tall order for Joe Biden to have escaped fully successful in achieving his objectives for the trip.

This is Joe Biden’s first trip as president to both Israel and Saudi Arabia, although, over the years, as a senator and then vice president, he had, of course, visited the region many times. But going there as president is different. If for no other reason this is because when the president speaks, he speaks for the government (and, potentially, for the nation as well). Crucially, under the American constitution, the executive branch (ie, the president) has primary responsibility for foreign policy direction and choices, even though budget decisions ultimately rest with Congress and treaty approval and confirmation of senior officials resides with the Senate.

Congress always has the option of holding hearings on issues, policies, challenges, and decisions – sometimes for purely partisan political advantage. One such example was that exhausting, 11-hour hearing marathon with then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton about the death of a US ambassador in Benghazi, Libya. Cynics would say that effort was designed to derail her presidential ambitions.

Accordingly, presidents and secretaries of state keep a watchful eye over congressional feelings on every foreign policy idea, as well as the ideas and intentions of a host of policy advocacy groups, special interest groups, ethnically connected advocacy groups, and business associations. All these can conceivably retard or advance foreign policy efforts through public campaigns and other efforts to mobilise their respective constituencies. Given all this, a trip (and the possibility of agreements, handshakes, disagreements, embarrassments, and public criticisms) that includes both Israel (and the Palestinian Authority) and Saudi Arabia (and a side meeting with various other Arab leaders while in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia) would seem to be a potential minefield or jackpot for vigorous contestation.

As the Economist judged it, “The real focus of Mr Biden’s trip would begin on July 15th with his arrival in Jeddah. Even Israelis acknowledge that they are a warm-up act. ‘He’s coming here first because it’s now clear to the Americans they can’t deal with their allies in the region separately, as we’re much better co-ordinated now,’ says a minister.

“The administration would like that co-ordination, long conducted in secret, to be more publicly acknowledged. Mr Biden will urge the Saudis to draw closer to Israel, and to pump more oil. He wants to avoid an American recession and a thumping for the Democrats in the mid-term elections.”

First, let us consider the circumstances of the Saudi Arabia stop, the more crucial of the two stops. Biden, as a presidential candidate, had vowed to make the Saudis – and most especially Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) – pariahs among nations. They would be held at arm’s length or further, a veritable skunk in the international community. There would be no kisses, no hugs, no sword dances or glowing orbs as part of any welcome when the president came calling this time.

In part this was – and largely remains – because of the repressive, misogynistic nature of the regime, and the royal family’s control over virtually every aspect of the kingdom. In part, too, it has been because of the country’s involvement in the Yemeni civil war with its manifold human rights disasters there, and the near-famine conditions in many parts of that very unhappy nation.

But more recently, too, the horrific death of Jamal Khashoggi, a US permanent resident and periodic contributor to various publications, especially the Washington Post, helped focus much public criticism and approbation. Khashoggi was almost certainly killed (and presumably dismembered) inside the Saudi consulate in Istanbul by agents of the Saudi government, presumably, too, on the orders of MBS, the man largely in charge of the Saudi government.

Despite these problems, Saudi Arabia has substantial cards to play in today’s world – and especially in their dealings with Joe Biden on his trip. As the Economist argued, “It would have been less controversial if it [the Saudi stop] offered the promise of real achievements. It did not. Israeli officials play down talk of a breakthrough with Saudi Arabia, with good reason. The kingdom is in no rush to make a deal. It will settle for incremental steps: Mr Biden is expected to announce in Jeddah that more Israeli airliners will be allowed to fly over Saudi airspace. On oil, even if the Saudis agree to pump more, it is unclear how long they can run fields at full tilt, and whether the world has enough refining capacity to turn extra crude into fuel that can be gobbled up.”

Most important, therefore, in spite of practical difficulties, the trip was planned to achieve at least the possibility the Saudis would eventually promise to ramp up their petroleum production sufficiently to help drive down petrol (gasoline) prices in the US – now peaking in the middle of the American summer travel/vacation season. In the end, the Saudis did not make such an explicit pledge in the two leaders’ conversations. Such a move, were it to happen, might trigger other Persian Gulf producers to follow suit, although not, of course, Iran.

The crucial, politically volatile price of petrol has been a major sore point with Americans – with considerable downside implications for Biden’s Democratic Party and their chances in upcoming midterm elections for Congress. The petrol price is a key part of the overall inflation level, now nuzzling up against 9% year-on-year in the US. Calling it “Putin’s price rise” as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has not particularly struck home with many voters, who seem to see it more as a reflection of President Biden’s inability to wrest the price down by some arcane, mysterious means. Crucially, the higher petrol price does not simply affect individual drivers. Instead, it also affects prices in virtually every part of every one of the country’s supply chains, thus helping drive the overall inflation level up.

Saudi Arabia could also have arranged to offer a change in the direction of its involvement in Yemen, leading towards bringing the civil war there to a negotiated end, rather than in just the fragile, temporary truce that exists now, thus reducing the food scarcity crisis gripping much of that unhappy nation. (Demonstrating just how interwoven things are internationally, the Ukrainian invasion by Russia has choked off grain exports from Ukraine, and commercial purchasers and UN food programmes have historically relied on such supplies, including UN operations in Yemen.) Similarly, the Saudis could have made public demonstrations towards the idea of loosening some of the more odious and repressive measures in effect towards women and domestic political opponents.

There might even have been an expression of official regret (but likely not an admission of complicity on the part of the prince, beyond saying those officials directly involved in the killing have been punished) for Khashoggi’s death, and quiet offers of compensation, but no one should really have expected very much on that score. Instead, Saudi government officials speaking to the media chose to repeat remonstrations by the prince to President Biden about various American misdeeds – what might be seen as offering an audacious version of whataboutism to an ostensible international partner and security protector. Of course the infamous fist bump between the two leaders became the big news, in the absence of major announcements.

Still, as the New York Times could report on the visit, “‘We’re getting results,’ he [Biden] insisted on Friday night as he emerged from a meeting with the Saudi crown prince, Mohammed bin Salman, who clearly sees the opportunity to get diplomatic rehabilitation after Mr. Biden refused to see him for months, accusing him of complicity in the murder of Jamal Khashoggi, the Saudi dissident and Washington Post columnist.

“Mr. Biden’s effort here to negotiate greater oil production – jarring enough for a president who came to office vowing to help wean the world from fossil fuels – is driven by the need to make Russia pay a steep price for invading Ukraine. So far, that price has been scant: Not only are the Russians continuing to collect substantial oil and gas revenues, they are even supplying Saudi Arabia, Reuters reported recently, with fuel for its power plants – at discounted prices.”

One other aspect to the visit was US-Saudi trade and investment cooperation, and here there were some modest signs of success. As the Times added, “Perhaps the most notable of Mr. Biden’s flurry of announcements with the Saudis was an agreement signed Friday night to cooperate on a new technology to build next-generation 5G and 6G telecommunications networks in the country. The United States’ main competitor in that field is China – and Huawei, China’s state-favored competitor, which has made significant inroads in the region.

“It is all part of a larger Biden administration effort to begin pushing back on Beijing in parts of the world where for years the Chinese government has made progress without feeling much competition.”

Another element, of course, stitches Saudi Arabia and Israel together in the American mind, as well as with those two nations, explaining why this trip had included them both. That, of course, is Iran. In one way or another, all three nations have made it clear that a future pathway for Iran to actually acquire nuclear weapons should not be opened.

With that in mind, it is also true the earlier six-party agreement Donald Trump had withdrawn the US from – but with continuing US threats that a nuclear line should not be crossed by Iran – had mysteriously been meant to preclude any such a development. So far, the inconclusive and spluttering negotiations restarted by the Biden administration to reach implementation of a modified or new agreement do not yet seem to have any kind of immediate result.

As a result, the Biden administration has been hoping to bring together the Israelis and Saudis via strong declarations that Iran must not move further towards the creation of such weapons. The other Gulf States and other nations like Egypt are also increasingly on the same page vis-à-vis Iran and, in that position, the Biden administration can be seen as building upon those “Abraham Accords” brokered by his predecessor (establishing formal diplomatic relations between Israel and several Arab nations). This is to help stitch together what is clearly a tacit but stronger defence and security posture that brings Israel in sync with other Arab nations.

That brings us to the first stop on this two-nation trip, in Israel. In contrast to the way he was greeted in Jeddah, Joe Biden’s arrival in Tel Aviv was more ceremonial, a recognition of Biden’s long-time support for Israel throughout his political career. In Biden’s talks with interim prime minister Yair Lapid, the Israeli politician seemed to go further about stopping Iranian nuclear success, hinting broadly that it must be stopped one way or another – thereby implying that if peaceful means didn’t result in success, there were always other avenues.

Lapid, of course, is not necessarily going to be in office all that much longer, as yet another Israeli election is scheduled for November, after the collapse of Naftali Bennett’s unwieldy coalition. That was a government that had included a wide swathe of Israeli political parties – and even the Arab Israeli grouping, Raam, whose representative was included in the coalition government. It is certainly possible former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu (or even Bennett) could come back into power after the election. But no one can say for certain at this point how it will all turn out. Netanyahu’s ascendancy would certainly give encouragement to those who argue dealing with Iran’s nuclear ambitions is something that must be done decisively – and sooner rather than later.

In the leaders’ conversations, there were discussions of the newer anti-missile system, the Iron Beam, being phased in to support the current system, the Iron Dome – a defence system that had been largely successful so far in largely stopping rockets fired from Lebanese territory into Israel. From the American side, such procurement would be subject to American congressional debate, even if passage would be likely.

But the question of a Palestinian state, or serious negotiations for one, was not a major theme of the trip. Some of this is a reflection that the Palestinian cause is, increasingly, getting less attention from other Arab nations, given their increasing concerns about Iran. This was true for Joe Biden as well, even as some had hoped he would have made a stronger focus on a second reporter’s death – the recent shooting of Palestinian-American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh while she was covering a clash between West Bank Palestinians and Israeli security forces – with the evidence pointing to the likelihood she was killed by a bullet fired by Israeli security forces personnel. The eventual forensic determination by American personnel that the shooting could not be conclusively pinned on the Israelis, as a deliberate effort to remove a reporter from covering the clash in Jenin, has not sat well with Palestinians who clearly expected a more definitive statement from Biden.

As far as Biden was concerned regarding the Palestinians, he did make a visit to the Palestinian Authority’s leader, Mahmoud Abbas in Ramallah, and pledged additional medical aid (largely reverting to the situation pre-Trump), but not efforts to strong-arm the Israelis on negotiations, or even to agree to the reestablishment of the US Consulate in Jerusalem that had been focused outward towards Palestinian territories, in contrast to the embassy’s focus on the Israeli government in Jerusalem. That closure was another legacy from Trump.

Following the Jeddah meetings with Saudi Arabia, the final part of the Biden itinerary was a meeting with senior representatives of the Arab Persian Gulf states and Egypt, again with the focus clearly on building a more unified stance vis-à-vis Iranian nuclear ambitions. Such a meeting did not, however, result in something some breathless reporting had argued was just about to happen – an Arab Nato. Nevertheless, as Biden framed the conversation, “We will not walk away and leave a vacuum to be filled by China, Russia or Iran, and we’ll seek to build on this moment with active, principled American leadership.”

But the most important issue – presumably uppermost on the minds of leaders in Saudi Arabia, Israel, and the US – is obviously Iran. From the perspective of those three nations, even if they disagree on almost everything else, mutual concerns about Iran should be enough to carry things forward. Even if the disappointments of human rights advocates, a portion of the Democratic Party, Palestinian rights advocates, and those who remain furious about the deaths of the two reporters – Jamal Khashoggi and Shireen Abu Akleh – have yet to have their concerns sufficiently assuaged, perhaps the best that can be said about this trip is that things did not get worse. This is true even if Joe Biden and MBS’ fist bump became a symbol, quickly exploited by Saudi officials, to say graphically they are back in the game.

Oh, and there is one more thing. Russian officials are reported to be travelling to Iran on the hunt to purchase military drone craft – presumably to use in their ongoing invasion of Ukraine. It does seem interesting that the Russians are on the prowl for military equipment in Iran, rather than making it themselves. How that comes out is going to be very interesting. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.