ESCAPING POVERTY OP-ED

Young people in Tshwane’s Ekangala battle challenges of finding work and affording a home

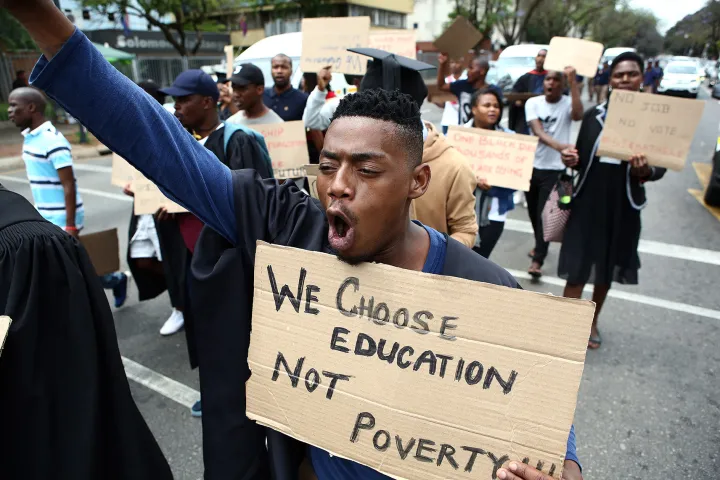

Twin challenges confront young people in Ekangala on the far edge of metropolitan Tshwane: Limited job opportunities and an inability to afford independent housing.

Across South Africa, young people’s lives are shaped by structural factors and policy-based interventions to do with housing and employment over which they have no control. These determine the local availability of work, the operation of housing markets and access to services in their neighbourhoods.

Read in Daily Maverick: Buy food or look for work — the awful choice facing young South Africans

This article explores what we, in our wider research project looking at South Africa and Ethiopia, call the work/housing nexus as experienced by young people in the greater Ekangala area of Tshwane. It illuminates the entanglement between the challenges and opportunities young people experience with housing, and their efforts to work or earn an income.

The young people we interviewed express clear aspirations around achieving independence, forging their own lives and obtaining privacy and self-determination. They say they dream of a time when “I am living my life and supporting myself.”

Yet, many battle with the costs of everyday living, particularly transportation. This is compounded when living on the urban periphery.

Costs, including those of internet data, narrow young people’s daily physical and online mobility, and their options for generating an income or securing independent living arrangements. Financial burdens directly reduce young people’s capacity to use education and training as a pathway out of poverty. Many young people in Ekangala described falling out of further education due to prohibitive fees.

Agency within constraints: the housing ‘choices’ facing Ekangala youth

In Ekangala, houses built by the post-apartheid government supply many deprived families with free shelter and a property of their own, along with water, sanitation and electricity. For young people without the means to live independently, this provides a home into adulthood, sometimes with a shared bedroom or for more privacy, in a self-constructed outdoor dwelling.

Living with family saves rent. For some young adults, the family ties are comforting, though others are frustrated by their dependence and lack of choice, but nevertheless value having a place to sleep.

Young people contribute to household costs when they can, but at times are supported by the social grants or earnings of relatives, including income from rental rooms in family yards.

“…it offers me… little privacy because I don’t stay alone. At the same time, it is also affordable to stay at home… I do not have to pay rent, water and electricity, and I am not forced to buy food.”

Some young people move with a partner or children into self-built structures on informally settled land, thereby gaining autonomy, but often having to contend with poor conditions including distant water, lack of electricity and provisional toilet facilities.

Renting a room in the yard of a formal house offers a better locality and relatively independent accommodation, but is unsustainable without a steady income.

A government house in Ekangala with extensions in progress (Photo: Mark Lewis)

Hustling and work in the greater Ekangala area

Employment opportunities in the greater Ekangala area are scarce and without qualifications, young people struggle to get a foot in the door. Factories at the Ekandustria business park, employing mainly men, have proven particularly uncompetitive and unable to attract investors. Work has declined significantly as a result of company closures. “Hopefuls” queue daily outside factory gates, but usually leave disappointed.

“…we have nothing. Here it’s dry, and ever since there haven’t been any firms by Ekandustria… A lot of people don’t work, a lot of the youth are just present here, so the only thing that I think can sustain is for one to sell stuff.”

Opportunities in the economic hubs of Pretoria or Witbank, nearly an hour’s travel away, are tempting, but prohibitively expensive taxi fares and limited bus provision require departing from home at unsociable hours such as 2am.

As renting in those urban centres while job hunting is unaffordable as a strategy, young people are forced to make impossible choices. In Ekangala, securing work occurs predominantly through connections and networks, and most young people feel excluded as a result. Young people hustle to generate an income, trying out various opportunities to assess their feasibility and potential for growth. Their portfolios are diverse, switching between selling low-cost items, offering services and seeking paid work.

A chicken business run by a young resident in Ekangala (Photo: Pretty Dube)

They’re often hampered by a lack of capital and poor access to Wi-Fi and viable local markets. Young people work hard to forge new skills through self-training, via YouTube for example, and they relish free skills enhancement opportunities and government-backed work experience.

The work/housing nexus

Work and housing are inextricably linked, especially for young people who often have little control over either, and are often waiting for “ownership” of both. Living in Ekangala proves a significant barrier to accessing work or training opportunities elsewhere, as costly and infrequent transport provision fails to overcome frictions of distance and time.

Locally, family houses provided by the state support some home-based businesses, although municipal regulations governing enterprises can hinder these at times. Spacious yards enable backyard dwelling construction which can provide rental income.

With earnings, young people can move to an independent self-built structure, but unstable circumstances or harsh conditions hamper the viability of this, requiring a return to the family house. Access to affordable housing through family provides young people with spaces of relative comfort as they navigate their dreams and efforts towards economic independence.

Overall, housing location relative to shifting sites of state intervention (such as Ekandustria, the industrial area historically government-supported, but no longer so) bears witness to altered politics, but also to rising and falling global-local economic rhythms and their immediate effects on residents. And state investment into housing where people are living, but where there is significant economic decline or collapse is evidence of the policy challenges of synchronicity.

We need to understand work in conjunction with housing, as a research problem and policy issue, to ensure they are addressed simultaneously so that young people have a chance of fulfilling their dreams. Resources supporting young people to find work or earn a living are critical, as is a recognition that affordable well-located housing is essential for sustainable urban living. DM/MC

Dr Paula Meth is a Reader in the Department of Urban Studies and Planning, University of Sheffield. She has a PhD from the University of Cambridge, and her research includes the themes of housing, urban change, gender and violence in the Global South.

Associate Professor Sarah Charlton teaches in the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of the Witwatersrand. Her research focuses mainly on housing policy and practice, state interventions in development, and people’s lived experiences of cities. She has a doctorate from the University of Sheffield.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.