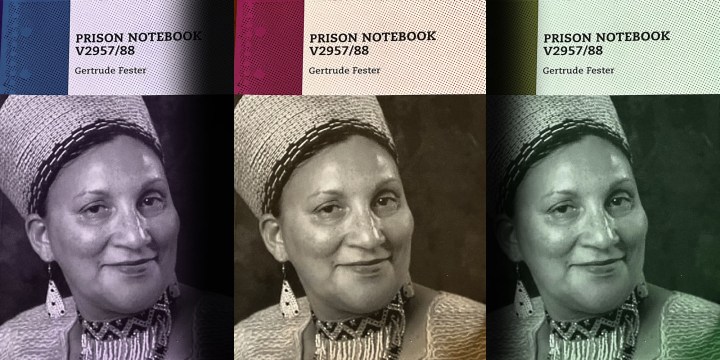

BOOK INTERVIEW

Rainbow trialist still holds a torch for a new nation despite the betrayal of Struggle ideals

In the so-called Rainbow Trial of 1989, the men and women in the dock gave an exciting glimpse of what the new country could look like. But it was not to be, as the ideals of people’s power and a united, non-sexist, non-racial nation did not fully find a home in the new South Africa. One of the trialists, Gertrude Fester, writes about those times in a new book.

One Sunday morning, a group of 10 to 15 patients, accompanied by a nurse because they were not allowed to walk on their own, left Valkenberg Hospital in Pinelands, Cape Town. They walked for about 30 minutes to the Video Shack to rent videos.

They were a motley bunch, Gertrude Fester writes in her newly released book, Prison Notebook V2957/88.

“Firstly, remember that the medication made us all walk as though we were floating in the air with blank facial expressions – or that is what I saw and experienced. Then some of us were dressed rather eccentrically – half pyjamas, and half dress or trousers. Some had a dress over their pyjama pants.”

The different pills affected those in the weird bunch, as she described them, differently. Some walked “with legs astride, others shuffled, while others walked with small steps. Some were wearing slippers, which made the shuffling appear worse.”

They found the shop closed, but undeterred and determined to rent videos, they walked next door to the owner’s house to explain their dilemma. They found a sympathetic ear and the business was opened. They were allowed inside and chose their videos for the afternoon and made their way back to a hospital known for giving psychiatric assessments of patients referred by the courts, or helping to rehabilitate mentally troubled patients.

The description of their adventure is a measure of the honesty, authenticity and frankness that permeates this book by Fester, a feminist and activist who spent two years in prison for treason.

The book is about her upbringing in a family classified as coloured, her political awareness, becoming part of the armed Struggle and the bitter disappointment of a revolutionary watching the noble goals of the liberation Struggle jettisoned.

Following her stay at Valkenberg – where she was admitted because she struggled with the mental effects of being held incommunicado for 104 days, during which she was tortured under Section 29 of the apartheid state’s notorious Internal Security Act – she made her mark as an ANC MP in the first democratic Parliament, and as a commissioner on the Gender Commission.

Now, as an emeritus professor at the University of Cape Town (UCT), the redoubtable activist has just released Prison Notebook V2957/88. “V” probably stands for “vrou” (woman).

Gertrude Fester and her mother Freda outside the then Supreme Court in Cape Town. (Photo: Rashied Lombard).

A tickey for lunch but no seat at the table

Fester, who turned 70 this week, said in an interview that writing about her life, encounters with the security police while on the run, her arrest and incarceration was a “traumatic experience”.

In the book, she reflects on her experiences with harsh apartheid laws, and on a relative who became a famous Afrikaans folk singer, hero-worshipped by some in the dominant culture into which he had married. This musician claimed in his autobiography he never knew he was black.

“But,” she writes, “he was a 16-year-old who occasionally serenaded his bewildered black cousins with boere liedjies and Jan van Riebeeck High School sports songs on his guitar on the farm.”

Segregation laws ignited in Fester an awareness of poverty, injustice, rights and privileges. There was no escaping the humiliation of apartheid for one not classified white.

Even the church was not immune. From her father, she learnt that when a delegate from St Stephen’s Church, the only coloured congregation within the government-supporting Dutch Reformed Church (NG Kerk), accompanied the dominee to synod meetings, he was not allowed to join the Afrikaner delegates for lunch.

This delegate would be told: “Here is a tickey [two and a half pence] for you. You cannot eat with us. Go and buy yourself something to eat at the shop.”

As a young girl, she enrolled in St Augustine’s Roman Catholic School in Parow, a conservative Afrikaans area, where for a year the deeply spiritual Fester thought about becoming a nun. She then transferred to Harold Cressy High School, one of the high schools in the so-called coloured education system that had a history of resistance against apartheid.

In love with drama, next on her horizon was UCT. However, the university offered drama as a second-year subject, which she could only take after having passed English 1, which she was yet to do. So, she attended the University of the Western Cape (UWC) for her first year before she could enrol at UCT and start her second, courtesy of a permit required by the government to study at a white university.

Disquiet about patriarchal power

During her sojourn at UWC in the black consciousness era, she was involved in the launch of the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso), which was initiated by Steve Biko and Peter Jones.

She writes: “It was an important vehicle challenging the apartheid ideology of ‘divide and rule’ [and] attempted to unite groups that had been divided by apartheid into Africans, African ethnic groups, Indians and coloureds. It was such a mental and psychological liberation to be introduced to the ideology of black consciousness.”

Invigorating as this time was, she was saddened by Saso’s all-male leadership and its abuse of power in the way they treated women. “I was quickly learning about patriarchal power and the abuse at all levels of society.”

She was also responsible for a small but historic change at UWC, where female students were required to wear dresses until 1971. Late for her lift one day, she pulled on trousers and unwittingly started to change this high school-like rule.

After a sojourn abroad, she returned to Cape Town and linked up with the United Women’s Organisation (UWO) where she again encountered patriarchy and the expectation that it should not be discussed. As she writes, “women themselves often colluded with patriarchy and camouflaged violence against women within progressive structures”.

Alluding to a factor still prevalent in democratic South Africa, she discusses remarks made by a woman, Lydia: “Lydia drew attention to the fact that while the anti-apartheid Struggle aimed at equality, patriarchy, non-sexism and democracy, the actual Struggle was permeated with inequality and patriarchy. This was the foundation of the tensions that existed between the male-led political structures and women’s structure from the 1950s to 1980s.”

She adds: “In terms of the feminist demand for equality in the form of comprehensive citizenship for women, sexism and patriarchal attitudes still pose a severe limitation on democracy and impact on women’s citizenship in the new South Africa.”

Going underground and meeting Hani

Working in the UWO was above-ground resistance. Later, she was initiated into underground work for the ANC and was sent to Harare, where she met Chris Hani. She was overwhelmed at meeting the Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) chief of staff.

“My heart was beating wildly. I took low breaths to prevent myself from enthusing unsophisticatedly. I tried to keep my voice from not reaching top decibels and I struggled to contain the excitement in meeting this legend,” she recalls in her book.

In her efforts to appear nonchalant, “I started crying. I stammered an apology.”

On her return to South Africa, Fester carried cash to bankroll MK activities. She was also drawn into more underground work against the South African state and became a marked woman who went on the run. Fellow guerrilla Bongani Jonas, who had been badly wounded while being captured, smuggled a message from prison to her that his interrogators were continually questioning him about her. He feared she would be assassinated and advised her to flee South Africa. She resolved to stay.

On the morning of 18 May 1988, the security police snared her, holding her in solitary confinement at Wynberg Police Station for more than 100 days. Denied any human contact except with her interrogators, she began hallucinating and was referred for medical treatment. A psychiatrist told her that being in solitary confinement for three months was causing pseudo-hallucinations. He recommended she get books to read. The security police ignored this recommendation.

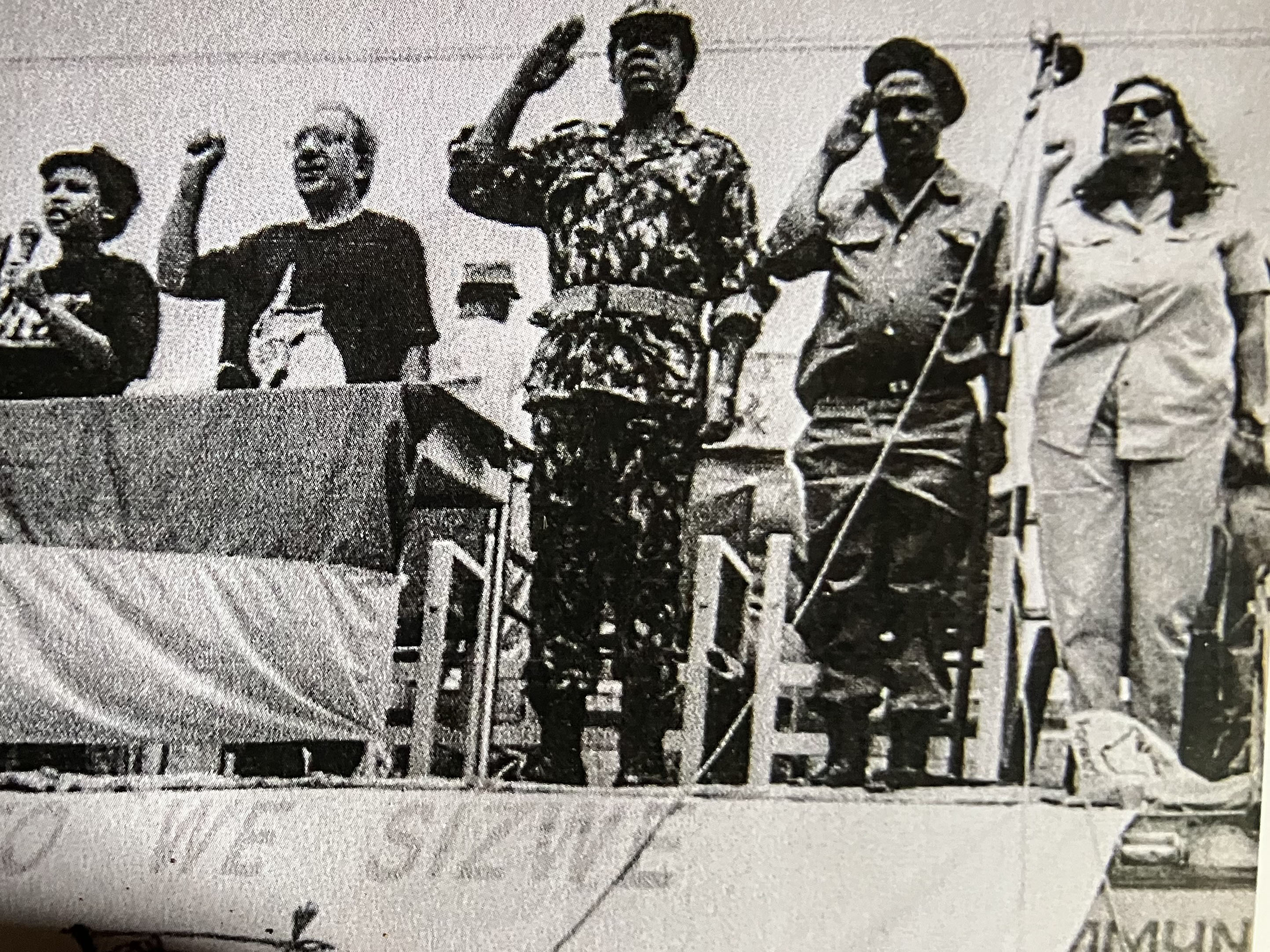

To escape the sheer torture of isolation and the debilitating effect on her mental health, Fester eventually signed a confession and was added as one of the 13 accused in the Tony Yengeni treason trial, with charges later being amended to terrorism. Because of how representative of the population it was, the media also referred to this, one of the last prosecutions of MK soldiers by the state, as the “Rainbow Trial”.

Reflecting on that trial this week, Fester said: “Our trial was a microcosm of South Africa. Four of us went to Parliament, four have died, two were living in informal settlements. One of the two, Alpheus Ndude, who turned 80 a month ago, only recently got a military house.”

In the end, the Rainbow Trial fizzled out. Charges were dropped and Fester was released after the unbanning of the ANC in February 1990, which culminated in the collapse of apartheid South Africa.

Undimmed commitment

Still an activist, Fester is angry that some of the men and women who had been in the Struggle when capture, torture, death or long incarceration were always be a strong possibility, are languishing in poverty, while others have feasted on the rewards of state power in high-paying government jobs, among others.

However, she still carries a torch for a rainbow nation, an ideal that the Rainbow trialists carried inside them when they became freedom fighters for change. Their commitment is a riveting part of her book. Many in politics should read it. DM

Dennis Cruywagen is the author of Brothers in War and Peace and The Spiritual Mandela. He is a former deputy editor of the Pretoria News, as well as the recipient of two Harvard Fellowships, a Nieman and a Mason Fellowship, and holds a master’s degree from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. He was also an ANC spokesperson.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.