Poetry Review

Lest we forget – Covid-19 and the many different kinds of love it brought us

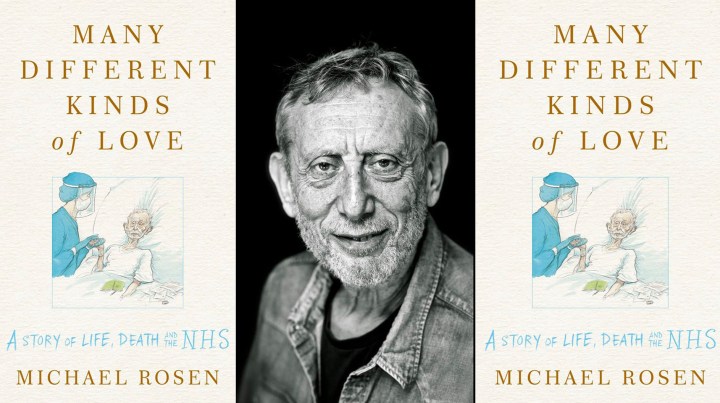

‘Many Different Kinds of Love’ by English poet and children’s writer Michael Rosen is an indelible testament to the suffering and deaths of millions during the Covid-19 pandemic. But it’s also a paean to the love and empathy of healthcare workers, families and friends whose dedication to loved ones and strangers saved so many lives.

Dear children, …

What we always have is now.

The moment before the next moment.

It’s only the next moment

we’re not sure about.

So whatever we’ve got to do

We have to do it now.

As Covid-19 drifts away (or does it?), with the world quickly taken over by other deadly crises, there are many who would have us gloss over the fact that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic took at least 15 million lives. Just as we are happy to forget about HIV, a virus that has caused 36 million deaths and is still killing people at a rate of nearly 700,000 a year.

Time to pull up our bootstraps and move on.

Thankfully Michael Rosen’s 2021 book, Many Different Kinds of Love, makes pandemic airbrushing impossible. Rosen’s extended poem is about nearly dying and then slowly recovering from Covid. It stretches over 200 pages but is of such simplicity and poignancy that it will stand as an indelible record for those who suffered with Covid-19 and still struggle to recover from its effects… and for those who died.

It is also a testament to the efforts and sacrifices of healthcare workers all over the world, particularly in Year One of the pandemic, before vaccines were added to their otherwise bare cupboard of medical treatments.

South African readers may not know much about Michael Rosen, a much-loved poet among British children and their parents, especially for his book We’re Going on a Bear Hunt.

They won’t know that These are the hands, a poem he had penned in 2008 to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the National Health Service (NHS), became the British equivalent of Jerusalema during the worst days of the pandemic, making him a national hero.

Or that it was into “these hands” that Rosen fell on 28 March 2020. These hands saved his life and, as he says in a segment comparing parental devotion to a sick child with the care he received at the hands of strangers, “as I lay there unconscious… night after night, /talking to me,/ telling me things,/

I try to fathom

This devotion.

They aren’t my parents.

Rosen’s Covid-19 coma story could be billed as an insider’s account of being snatched unexpectedly by a new virus and then the process of his imprisonment, rescue and recovery. It is recalled in his own sparse poetry and in the Patient Diary of the healthcare workers who cared for and kept watch over him during his coma – and wrote messages to him each day as they finished their care shifts.

The story’s simple: he was infected in late March 2020, when governments, including his, were still downplaying Covid and ignoring World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations (“It seems as if they thought they knew better”). Chance and the love of his wife Emma got him to hospital just in time where, such were the ravages of SARS-CoV-2 on his lungs and other organs, that within days he was put into an induced coma.

He spent the next 47 days unconscious. Eventually he was lured out, as much by love and music as medicine.

Rosen’s power is that he can speak, literally, for those who survived and those who died because he has been in both camps. With a faint nod to Hamlet, he says:

I’m a traveller who reached

the Land of the Dead.

I broke the rule that said I had to stay.

I crossed back over the water,

I dodged the guard dog,

I came out.

I’ve returned.

Having spent between 6 April and 20 May 2020 in an induced coma, Rosen knows the in-between land – except that by his own admission, he doesn’t. Because his coma days are a blank in his memory.

The coma keeps secrets.

There is no place for the coma in

the geography of my memory,

I can’t visit the coma.

I can’t call for it.

If i try to find it,

if i plead for it to come,

it doesn’t hear.

Or if it hears,

it refuses to come out of its cave

And tell me what happened.

Thereafter the poem(s) are about his recovery and the thoughts it gives rise to: a survivor’s account on learning to breathe, feed, bathe, walk, talk, climb stairs:

I think they’re weaning me on to breathing air.

Coming off the stuff that comes through machines.

It is also about the journey to learn to live with his post-Covid self. Recovery involves a reassessment of life and living: “we are always becoming”, he realises. “I am not sure I am me.”

The power of Rosen’s poems lies in the way they are narrated.

Literary theorists would call it blank verse. Little rhyme. No literary tricks. No iambic pentameter. Just bare words. Broken into short lines of uneven length. Quietly sardonic. Occasionally humorous. Intensely individual yet deeply existential. One man’s story and many people’s story.

Connection.

Their poetic power stems from the unexpected feelings the words call up for us and for Rosen himself. For example, death’s proximity to him brings inevitable recollections of the death of his son Eddie at the age of 18 – “I know death” – a loss he has also written about in Sad Book.

This is an extended poetic meditation, talking about life’s profundities, uncertainty and fragility from the vantage point of one who was on the edge. Reductio ad essence:

We are a collection of tubes and pipes.

Some big.

Some tiny.

Sometimes the plumbing goes wrong

or a pipe gets blocked.

There is little rancour. Even the Covid denialists are given short shrift in poems that fittingly last only a few lines – and yet are deeply personal. “I’m busy trying not to be dead” he replies to a critic of lockdowns who tweets to him that “you are not half the man you used to be”.

Ultimately, there is a moral to Rosen’s journey. But he doesn’t dwell on it because the poem is the moral. But in case you’d like the summary, it is an epiphany that comes early in his recovery, as he describes his response to a doctor asking him “whether I’ve had:

Hallucinations or nightmares

Or terrifying delirium.

I say no.

…,

‘I’m disturbed by another dream.

I imagine that just before I got ill

I came across a statement, a kind of manifesto

from a German farmer.

It was a reply to the hate coming from

neo-Nazis in his neighbourhood.

He comes towards me

wearing a stone-washed bib-and-brace.

He stands alongside his 1950s tractor

With his family around him.

His manifesto tells how we can only

Go on if we love each other,

We have to find many different kinds of love

He says, love for lovers, love for our children,

Love for our colleagues, love even for people

we don’t know.

If we don’t, we will destroy ourselves.

What makes me sad about this dream

is that I keep getting to the point

Where I am thinking:

Where is this manifesto?

As we veer away from the things Covid should have taught us, missing the moment to build back better, Many Different Kinds of Love is a book that shows the deep kindness and connection that we often find in humanity. It plumbs depths of despair and loss, but refuses self-pity. It distils the essence of life, love and caring into the barest of terms, relying on recognition and connection, not pontification or polemic, to remind us of the meaning of life. And of death.

People stop me in the park

And say they’re glad

I’m up and about.

I guess it feels to them

as if I’ve postponed death,

Fended it off a little longer.

I don’t want to be the messenger

of false hope though.

I didn’t cancel death.

it just didn’t happen right then.

…

Here though,

I’m in the midst of beginnings: …

DM/ML/MC

This review is dedicated to my friend Vanessa Merckel, who died on 12 July 2021 of Covid-19, shortly after being awarded a PhD for her research that explored the power of love.

Many Different Kinds of Love is available at Exclusive Books. I’m grateful to my friend Stephen Faulkner who gifted it into my hands at just the right moment.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thanks for sharing this, Mark.. One quibble – it’s free verse, not blank verse.

Thank you, Mark. In the wash of sad and bad news, you find good, humanity and love.

Perhaps it is time to ponder on a “remembrance day” to capture what we all went through during the worst of the pandemic… obviously we survived, but we did not escape unscathed, we lost people we knew, we were “incarcerated” for weeks on end, separated from loved ones, fearful of our future, the lack of treatment options, images of medical staff fighting to save us, the “them and us” vaccination divide, many lives and livelihoods lost, the road to recovery…

This review made me think of all of these things and it reminded me “lest we forget”. Thank you