PIRATE MINING OP-ED

The shine dims on South Africa’s chrome as ruthless pirates muscle in on mining operations

By some estimates, South Africa — the world’s biggest producer of chrome ore — now loses about 10% of its production each year to illegal mining, amounting to 600,000 tonnes of stolen material.

Military helicopters descended on a mine in South Africa’s North West province earlier this year to disrupt a massive illegal mining operation.

Soldiers rappelled down ropes as police and security guards encircled the property. One miner, recording the raid on his cell phone, yelled, “things are looking bad here!” Another suspect fled the scene in his pickup truck, ramming through a gate before being captured in a shootout.

The miners had been excavating chrome ore, an essential mineral for manufacturing stainless steel.

Taking advantage of loopholes in South African law, they had posed as legitimate companies, operating with heavy machinery in broad daylight.

Investigators estimated that the syndicate was making off with R1-million of ore per day. Police confiscated 20 machines, including trucks, excavators and diesel tanks, as well as more than 2,000 tonnes of chrome.

This was not an isolated case, but part of an insidious and hugely lucrative illicit economy that has flourished in South Africa in recent years.

By some estimates, South Africa — the world’s biggest producer of chrome ore — now loses around 10% of its production each year to illegal mining, amounting to 600,000 tonnes of stolen material.

This chrome is exported in bulk, primarily to China, without generating tax revenue in South Africa. Its relentless extraction has devastated rural landscapes, in some cases practically swallowing entire villages, and is increasingly associated with reports of violent control.

For the most part, this harmful trade has gone unpoliced, although the raid in April showed that the authorities may be adopting a firmer stance against illegal chrome mining. Much of the damage, however, has already been done.

“The state relinquished control” of the industry, one analyst explained to the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organised Crime.

“Now it’s the law of the jungle.”

An age of chrome

In a country notorious for its problems with illegal mining — from gold and diamonds to coal — it might seem inevitable that chrome ore is being targeted.

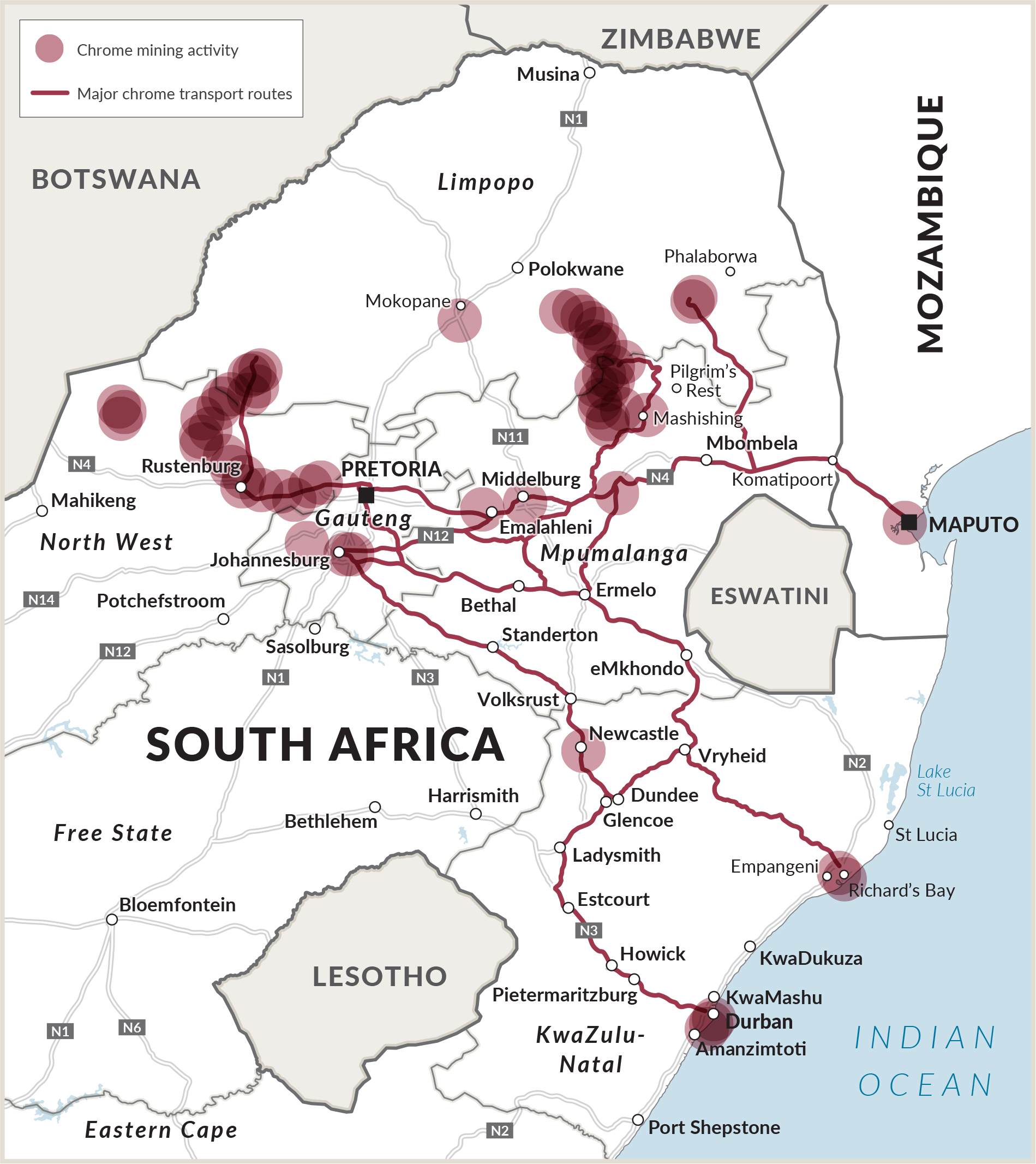

South Africa is home to around a third of the world’s chrome reserves, mostly occurring in the northeastern parts of the country. But South Africa’s illicit chrome trade only became possible due to a series of recent events in the chrome industry.

Source: Data from AmaranthCX

Chrome mining began in South Africa in the 1920s. During the apartheid years, buoyed by access to cheap electricity, the country developed a major chrome refining industry.

By the early 2000s, 90% of the chrome ore mined in South Africa was being smelted locally into ferrochrome, an alloy of chromium and iron vital in the manufacture of stainless steel.

Over the past decade, global demand for stainless steel has doubled, driven primarily by urbanisation in China. As a consequence, the market for chrome ore has boomed. To feed this growing industry, South Africa initially provided China with ferrochrome, smelted locally.

But in the first decade of the 2000s, South Africa’s chrome-refining industry suffered a major setback with the onset of power shortages. Owing to government corruption and mismanagement, the country’s power plants could no longer keep up with demand.

Refining chrome ore is exceptionally energy-intensive; furnaces typically reach temperatures exceeding 1,700°C and the ferrochrome industry consumed around 5% of South Africa’s entire electricity budget.

As the power crises deepened, many smelters shut down. Some were paid by the national power utility not to operate in an attempt to free up electricity for other users. At a moment of surging demand for ferrochrome, the world’s major producer was in serious trouble.

China, meanwhile, started producing its own ferrochrome. By 2016, its output had overtaken South Africa’s.

This meant that China’s import needs shifted towards chrome ore — which some producers in South Africa began exporting directly, rather than using it to supply local refineries.

During this period, China also switched to using lower-grade chrome ore to manufacture ferrochrome and stainless steel. South Africa has ample surface deposits of this material — both naturally and as a by-product of platinum mining — which produces so-called “fine” chrome during the refining process.

For decades, platinum producers had simply dumped fine chrome at the surface, but now it became feasible to re-mine those areas. Legitimate companies began mining surface chrome in its various forms — as did illegal mining syndicates.

“People with nefarious goals took the gap,” an expert on chrome production explained. The foundations for a new illicit trade had been set.

The rise of chrome syndicates

South African investigators first became aware of illegal chrome mining in 2016.

In a parliamentary briefing the following year, police officials said that “unemployed youths and elderly women” had begun mining in harsh conditions, equipped with inadequate tools.

Reports soon followed of powerful equipment, such as front-end loaders and cargo trucks, being used to illegally mine and transport vast amounts of chrome ore.

Industry analyst Paul Miller recalls “double-decker trucks stealing chrome”. According to Miller, entire valleys were taken over by “pirate miners”.

These miners were able to operate, in part, by exploiting weaknesses in South African mining policy which had created new provisions for small-scale and artisanal miners — an attempt to address long-standing problems of racial exclusion in the industry.

These permits were intended for mines smaller than five hectares and less burdensome to apply for, requiring, for example, no environmental or social plans.

But in practice, they provided a veneer of legitimacy for illegal chrome miners. Flouting permit conditions — mining beyond the boundaries of a concession or digging too close to homes — came with few consequences. Disputes were treated as civil, rather than criminal, matters.

Sensing an economic opportunity, some traditional leaders began granting permission for chrome mining on communal lands. Chaos ensued.

One ward councillor in Limpopo posted pictures on Facebook of excavators digging close to buildings in pits deeper than 10 metres.

In an interview for local television, a village headman in North West said: “The land has been turned upside down.”

But the mines had grown too big to control. “We are afraid to complain,” one villager explained, “because when we do, they use force to silence us.” Heavily armed guards have appeared at some sites.

According to some in the industry, Chinese chrome buyers have been providing miners with weapons to defend their turf, although it is unclear how common this practice has become.

Miller described “Congolese men with AK-47s” standing outside illegal chrome mines. “It’s crime organised on a major level,” he said, “but if you go there, there’s a permit.”

There have been signs of more serious criminality encroaching on the trade, including hostile invasions of legal chrome mines — “mine hijacking”, as the Mineral Resources Council described it — and reports of chrome ore being stolen at gunpoint.

For miners, meanwhile, the work is perilous. One miner died in 2017 during a rockfall, with another death in similar conditions barely a month later. In 2018, a woman in her 50s died when, according to a police spokesperson, “a huge rock and rubble collapsed and buried her alive”. Another miner died in an explosion in the same year. Further deaths were reported in 2019 and 2020.

Investors in this wildcat industry included a former apartheid assassin who was later implicated in stealing military weapons and dealing illegally in uncut diamonds.

After he struck a deal with residents of one village in Limpopo, “there were at least 100 trucks leaving this area every day, filled with chrome”, a community member recalled.

Industry insiders speak of “scary Afrikaners you don’t want to mess with” controlling the flow of ore.

‘A bulk commodity illegal industry’

To facilitate the flow of illegally mined chrome, an entirely new infrastructure has developed, connecting mines in Limpopo and North West with deep-water ports in South Africa and Mozambique.

First, the ore is processed at aggregators known as spiral plants. A recent mapping exercise identified at least 20 of these facilities in areas with no legal mining operations, which suggests that they are processing stolen ore.

From the spiral plants, upgraded chrome is trucked to Mozambique or inland to Johannesburg, where it is warehoused, containerised, and delivered to Durban or Richard’s Bay for export.

Along the way, this chrome vanishes into the legal supply chain, leaving no trace of its illegitimate provenance.

“It’s a bulk commodity illegal industry,” Miller said.

There are no restrictions in South Africa on the transport, sale or processing of chrome ore, leaving little recourse for the authorities beyond controlling the mines.

In 2017, police recorded 42 arrests and confiscated 22 trucks and 14 excavators, and more seizures have been reported since then.

However, even stricter enforcement will do nothing to reverse the damage wrought by illegal chrome mining, visible in satellite imagery as vast scars on the earth. Halfway across the world, this material has been fed into blast furnaces and cooled into metal, feeding the expansion of Asian cities.

If there is an end to this story, it may come with the exhaustion of surface chrome deposits, which have declined rapidly. But there are concerns that mining syndicates, enriched by chrome, may already be turning their focus to other commodities, such as coal and sand.

“You’ve capitalised these pirate miners,” Miller said. “If they exhaust the resource, they’ll find others.” DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally. To receive monthly Risk Bulletin updates, please sign up here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.