HORSE RACING (PART 1)

Odds against the Sport of Kings, the last stand for Thoroughbred horses

The ancestors of the horses we see today originated on the Asian Steppe and were probably captured and ridden about 3,000 years ago. As transport in peace and war, they utterly changed human civilisation. No longer a necessity, they’re now mainly used for sport and leisure. In the first of a four-part investigation into horse racing, we look at the rock stars: Thoroughbreds.

Horses are born to run and when they do, they’re beautiful to watch. Thundering across a plain, mane and tail streaming, hardly seeming to touch the ground: it’s a sight that has enthralled humans for thousands of years. Nervous wariness was their nature and speed their protection from predation.

It was for their strength and speed that we became their primary predator, not to eat — though they were eaten — but as transport.

The horse became a metaphor for royalty and power, a symbol of elegance, primary creatures of conveyance and chariots of war. They kicked human civilisation into fast forward and it’s never looked back.

But it’s over.

This is the horse’s final century — their strength replaced by machinery, their memory living on in statues, paintings and the pits of knacker’s yards throughout the world. Though engines are still measured in horsepower, they no longer involve horses.

Their last redoubt is the world of sport.

It’s unlikely they’d choose to run around a track with a human on their back smacking their flanks. But they’re required to do so in very large numbers, sometimes earning their owners and those who bet on them huge sums of money, and sometimes dying.

The fate of those who can’t stay the pace is worrying.

In South Africa, the National Society for the Protection of Animals (NSPCA) notes two types of horseracing: Thoroughbred racing and bush racing — and disapproves of both. That’s far too simple. While formal racing involves only Thoroughbreds and well-kept tracks, months of digging by Daily Maverick came up with an additional range of styles and places where racing takes place on a weekly basis.

There’s tripling, trotting and flat racing, as in flat out, (all of which can be formal traditional racing), dirt racing and street racing. Some traditional races have well-kitted horses and jockeys, some horses are much-admired and ridden bareback and still others are horses in terrible condition (sometimes ridden to death). There are reports of township races on tar by youths high on tik.

In this, the first of a four-part series, we investigate an institution in decline: Thoroughbred racing. They’re the kind of horse you see on advertisements for cigarettes and booze, replete with yelling crowds, stylish outfits and beautiful horses throwing back their proud heads for the TV crews.

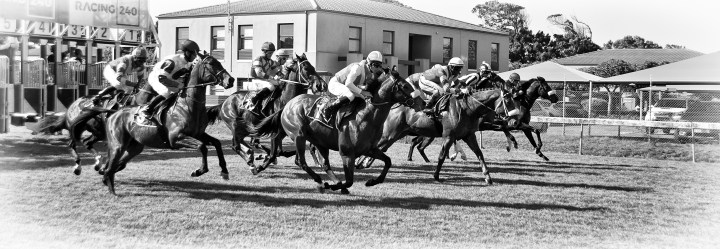

Casinos, slot machines and the Lotto have pushed horse racing off its former pedestal as the only betting game in town. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

Thoroughbreds were developed in 17th and 18th century England, when native mares were bred with imported Oriental stallions of Barb, Byerley Turkoman and Darley Arabian horses. Apparently, all modern Thoroughbreds can trace their pedigrees to three stallions originally imported into England in that period.

They’re preferred for racing because they’re tough, fast and perform with maximum exertion. A Thoroughbred can reach over 60km/h in six strides taking just 2.5 seconds, which beats a Ferrari.

American biokinetics engineer George Pratt was awed by their energy potential: “The horse that walks around, eats grass, looks at the view and gives every appearance of tranquillity was, in fact, designed by God to explode.”

But high speed and exertion can result in accidents and health problems such as bleeding from the lungs. This means they have to be handled with care.

In South Africa, Thoroughbred racing is shrinking and becoming less profitable, with declining breeders, jockeys and even race tracks. An obvious place to start exploring the world of fast horses is a race track.

The races

Kenilworth Race Course in Cape Town on a Wednesday had none of the buzz of excitement the hype of racing leads you to expect. Despite beautiful winter sunshine, the stands were empty, a few owners and trainers were standing around chatting and horses were peering over stable doors. Perhaps there are buzz days, but this wasn’t one of them.

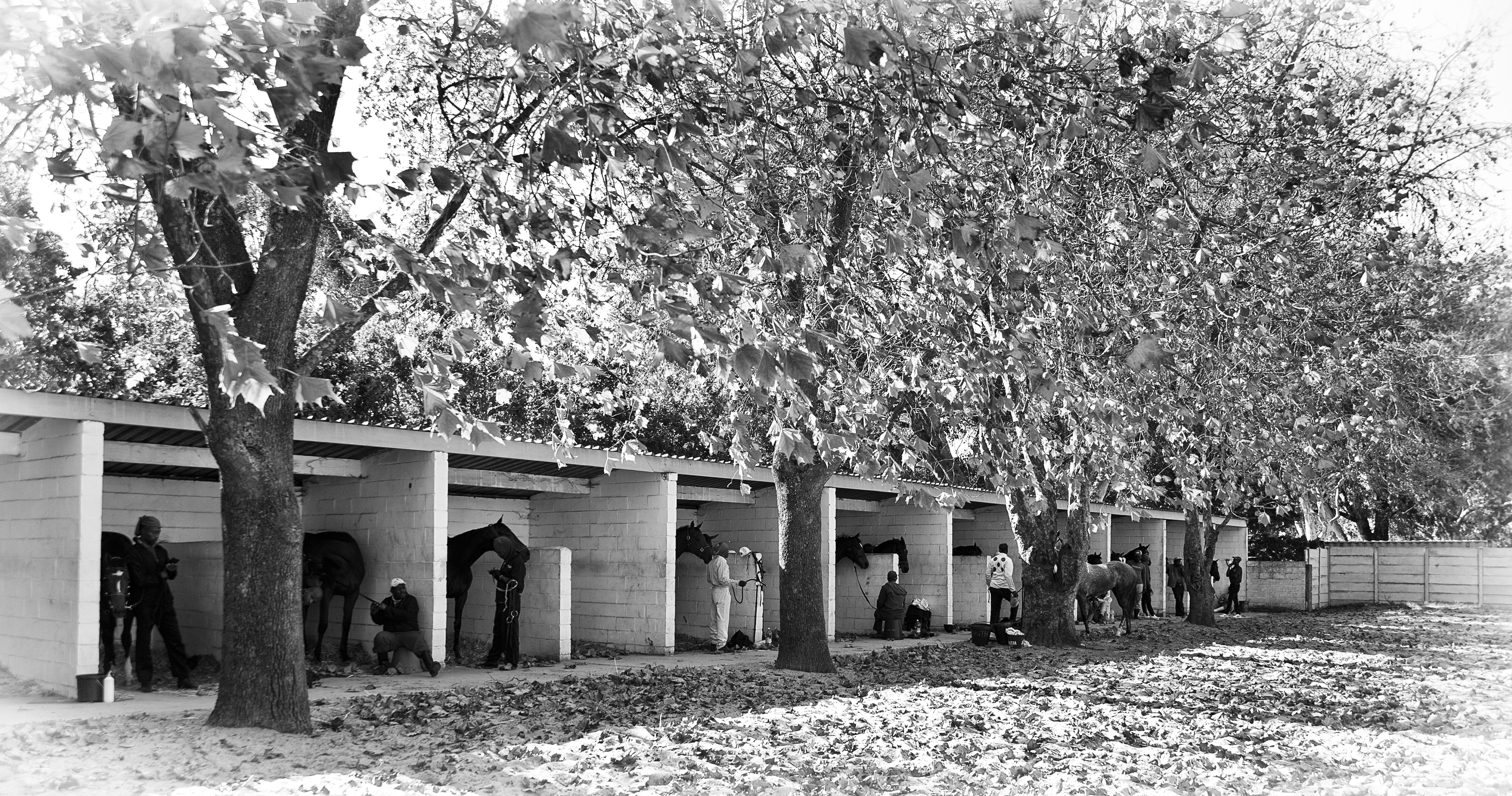

The buildings of Cape Racing’s star course are beautiful, the trees of the parade ring are old and shady, the track is thick lawn grass and the stables are spotless. It has genteel, old-world charm.

Despite a missing fourth element of racing — yelling crowds — the other three were in place: the horses with their owners, trainers, grooms and jockeys, the control systems and what can best be described as the punter’s film shoot, which records races and broadcasts them to betting shops, home computers and television screens around the world.

Deep below the stands, surrounded by screens, chief stipe (stipendiary steward) Ernie Rodrigues and his team were monitoring every aspect of the race.

“We’re here entirely for the welfare of the horses,” he said. “We see any problem, we pull the horse.”

They’re mostly former jockeys and know horses intimately. They’re supported by two vets who inspect each animal — one at the start and the other at the end of each race.

The jockeys, weighed (and barred if overweight) then ride their horses to the starting gates which, on signal, clang open and the horses explode into action. The winning jockey and horse are led into a small winners’ enclosure to be interviewed, filmed and photographed.

The whole affair — from owners, horses, safety checks, races and prizes — has the air of a closely choreographed live-stream film shoot packaged for worldwide betting audiences who participate using their credit cards by “owning” a share of the horse for the duration of the race.

Money is won, but more often lost.

The system

In South Africa, horse racing dates back to 1795 and evolved through individual clubs centred on city tracks, with betting run by totes. The term tote comes from totaliser, where the money bet is divided among those with winning tickets, less the tote fee and tax.

If you were the betting type before other forms of gambling kicked in, horseracing was the only game in town. You could go to races and place bets or queue at grubby off-course totes and put money on your favourite horse.

The sport had always been heavily taxed at provincial level.

But then came bantustans — faux-independent “countries” dreamed up by apartheid. Free of South Africa’s gambling laws, they permitted casinos with card tables and slot machines. Then, in 2000, the Lotto arrived and, together, these systems dangled life-changing wins and were taxed at lower rates. Horseracing took a knock from which it has never really recovered.

Thoroughbreds are given five-star treatment, but what happens when their racing days are over? (Photo: Don Pinnock)

A few Highveld clubs got together and petitioned the Gauteng government to lower their tax burden. It agreed, but insisted they rationalise, leading to a corporatisation process.

This resulted in the formation of three geographical organisations based, respectively, in Gauteng, KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape. They’re licenced through the National Horse Racing Authority (NHA) of southern Africa (including Zimbabwe) and funded by punters through totes. Bets are also placed through bookmakers offering various combinations with far higher individual winnings.

The NHA keeps good statistics. For its officials housed in lavish offices in Turffontein, Gauteng, those stats must be extremely worrying.

According to NHA chief executive officer Vee Moodley, the horseracing industry is contracting at an alarming rate: “The current pandemic and economic climate conditions are wreaking havoc on a local and international front,” he wrote in the annual report.

“The South African Racing statistics for the past 30 years give an overview of the decline of the industry.” He warned it was in danger of falling into a state of anarchy.

The Thoroughbred Breeders Association echoed his concern.

“The TBA is of the view that the situation in which the sport of Thoroughbred horseracing currently finds itself is dire. Without immediate government intervention, the sport may not survive.”

From 1990 to 2020 the number of starters in NHA races dropped from 49,482 to 35,232 horses — there was a 37% reduction in trainers and 33% fewer jockeys.

Between those years, half the formal racecourses in the country closed and there was an 84% drop in breeders or stud farms (though average earnings per horse jumped from R13,000 to R44,000 — 238%).

According to owner and racing journalist Robyn Louw, this is probably because of the rising cost of producing them and an uncertain yearling sale market.

“I would guess that, due to the cost of keeping a racehorse, people are quicker to retire the less good ones and more careful about placing the ones who have a chance to earn. Therefore there are fewer starts per horse (which seems to be the trend worldwide), but they’re trying to make each start count,” she said.

Over tea at a fancy club, a horse owner who did not want to be named explained the current problem:

“There’s so much gambling competition and horseracing clubs haven’t looked after their customers. If you think of a casino with all sorts of packages and food and linked hotels — they’re customer-focused. And the Lotto is so much easier and more accessible.

“You don’t need brains to buy a Lotto ticket. Horseracing requires homework and understanding the mathematics of it.”

Racing was already in trouble from competitors for the gambler’s purse, then came the Steinhoff debacle. In 2017, the international Steinhoff group set up by its then CEO, Markus Jooste, was investigated in Germany for accounting irregularities and shares collapsed, losing R300-billion in market value.

Linked to it was a holding company called Mayfair Speculators owned by Silver Oak Trust, consisting of Jooste and his son-in-law.

Mayfair housed Jooste’s racehorse business with the largest horse breeding farm in the country, stabling hundreds of the country’s top horses. It went under, placing around 300 Thoroughbreds on the market.

Thoroughbred racing’s problems didn’t end there.

In 2019, Phumelela Gaming & Leisure, the JSE-listed horseracing and betting tote in Gauteng — with many directors reportedly linked to Jooste — was dragged to court by the Public Protector for privatising the country’s horseracing industry.

It controlled Turffontein, The Vaal, Kimberley (Flamingo Park), Fairview and Arlington in Port Elizabeth and had a management agreement in place with Cape Racing. This essentially meant it controlled all the formal racing venues in South Africa outside KwaZulu-Natal.

As its troubles mounted, Phumelela went into business rescue with a debt claimed at R1.7-billion, placing racing throughout South Africa at risk.

The sport was saved by the formation of 4Racing by Mary Oppenheimer and Daughters with an investment of R560-million.

A similar racing rescue was required in Durban, saved by what amounts to a takeover by the bookmaker Hollywood Bets, the main sponsor. Its CEO, Owen Heffer, is one of the biggest racehorse owners in the country.

Amid all that, the pandemic hit hard, closing down all racetracks for months with costs unremitting and no revenue coming in. The prospect for Thoroughbred racing in South Africa has never looked worse.

The owners

You have to be wealthy to breed and race Thoroughbreds, but that doesn’t mean racing them is likely to be the source of your wealth. The reason is that relatively few horses ever win race prize money and the cost of keeping them is high.

A Thoroughbred can reach more than 60km/h in six strides taking just 2.5 seconds, which beats a Ferrari. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

A large number are bred to be sold at yearling sales to new owners who hope to race them. But you can never tell if that will pay off either. It depends on your skill at spotting a potential winner — and that’s often a hit-or-miss business.

“You used to be able to make money out of breeding racehorses,” said the horse owner I quoted earlier, “but it’s increasingly becoming an expensive hobby for people who have other forms of income to support it.

“A mare has one foal a year. I may have 20 mares and it costs a considerable amount to have them covered by top stallions. There can be birth or deformity problems, so maybe I get 15 foals. It costs around R10,000 a month to raise a Thoroughbred to race age. You sell some when they’re a year old, keep some.

“Somebody buys a yearling for, say, R200,000… it costs them R120,000 a year to keep, so you’re in for over R300,000 by the time it hits the track.

“Maybe you get lucky, it wins a few races. That money doesn’t come back easily. Horses are fragile, it tears a tendon, have a break — there’s a whole host of things that could happen.

“You used to be able to write off your losses to tax, but that’s no longer possible. In the past, if one of your horses won, it would pay for nearly a year’s keep for your stable. Now, with rising costs, you might pay for two or three months. We used to export horses overseas, but with African horse sickness restrictions, that’s now a problem.”

With the radical decline in the number of breeders, stud farms, racecourses and jockeys, and with tote problems, formal Thoroughbred horseracing is clearly not a sport you’d place your bets on. But some have, in spadefuls.

The totes and bookies

Horseracing is about horses and racing, right? Wrong. It’s about money… huge amounts.

You’d be excused for thinking horse owners race to add to their wealth, but in comparison to the totes and bookies, they’re small cheese. Let’s look at the numbers, starting global.

In 2021, the world’s income from online gambling alone was R3.7-trillion, the 49th biggest industry on the planet. About 26% of the global population has gambled at some time, but only 13.5% win in the long run.

The South African Gambling Board estimates one in 10 South Africans engages in gambling activities and the revenue spent is growing at around 6%.

Gambling addiction is huge, with at least half of problem gamblers becoming involved in crime to feed their addiction. Basically, gambling is a mug’s game which drains income if you gamble but can make you rich fast if you organise it.

Let’s spool back to horseracing. Every single day of the week in South Africa there’s an NHA-sanctioned Thoroughbred race meet in progress, with anything from 75 to 95 horses competing. In 2020 there were 3,457 races.

Thoroughbred racing in South Africa is shrinking and becoming less profitable, with declining breeders, jockeys and even race tracks. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

An example of a Group 3 stake is Strelitzia or Godolphin Barb at Scottsville racecourse. The total pot for each is R175,000, portioned out at R109,000 for a win, R35,000 for second place and R17,500 for third place (that win is less than it costs to keep the horse for a year).

The average pot for a Group 1 race like the Durban July is a lot more — about R1.8-million — but there are far fewer such races.

Each year, more than 26,000 entries from among 44,444 registered Thoroughbreds will be chalked to races across six NHA tracks netting R255.8 million in prize money. That sounds a lot, but not relative to the country’s 368 totes and bookies.

According to 2019/20 Gambling Board statistics, they netted R2.5-billion in revenue for horseracing.

An eye-watering sum? Nope, a drop in the ocean of total gambling revenue of R32.7-billion a year, earning the South African government just R3-billion in taxes. How’s that for a low tax return?

By comparison, the business information outfit Who Owns Whom says the more traditional gambling industry — which includes horseracing — is facing unparalleled losses.

Of course, revenues are better if you do it illegally. The Gambling Board estimates that illicit gambling drains R1.9-billion a year from the fiscus in undeclared money.

A quarter of a century ago, horseracing was the only gambling outlet.

Today, the king is casinos at 64% of turnover, with betting on all sports trailing at 16.8%. But if you’re the betting type, it pays not to be too snooty. The most consistent money earner is online bingo.

There are two takeaways from all of this.

The first is that, for Thoroughbred owners, you have to be doing it for the love of the sport — because you can’t be doing it for money.

Racing and race tracks are being kept alive by totes and bookies who need owners to shell out for top-class horses so they can rake in the loot. That might explain the 84% drop in breeders and stud farms in the past 20 years. In a tough financial climate, why pay to feed the sharks?

And second, as Thoroughbred racing declines, informal racing is booming. But, not being regulated, it’s often anarchic and sometimes spontaneous. There are no welfare regulations for the horses. And there’s no control over races or incomes earned by owners and under-the-counter bookies from events taking place at hundreds of venues around the country.

Before we look at that, though, questions need to be asked about where Thoroughbreds go when they’re no longer winning races or useful breeders (only about half of those registered are entered in formal races).

Between the NHA racing industry and the sometimes heartbreakingly cruel informal system is a thread that needs following. DM

Tomorrow: Part 2: In search of lost racehorses.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.