NIXON, WOODWARD, BERNSTEIN

Watergate at 50: The scandal that changed everything, more relevant than ever

The Watergate crisis in America occurred half a century ago — but its effects have rolled on into our present. And it should remain a signal lesson for the future.

This week, while South Africans are contemplating the legacy of the 1976 Soweto Uprising and how it helped set in motion the end of the apartheid era, there is a second anniversary this week that should be recognised as well — 2022 marks the 50th anniversary of the Watergate break-in in Washington, DC.

That criminal conspiracy had been carried out by individuals operating at the instruction of President Richard Nixon’s White House — and it ultimately triggered a political tsunami that drove a president out of office.

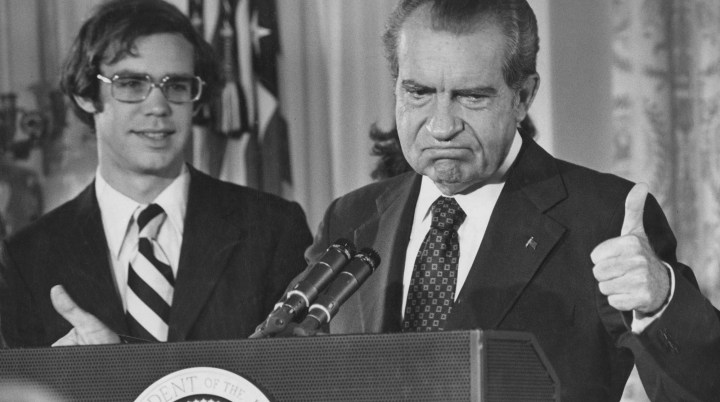

American president Richard Nixon announces his resignation on national television on 8 August 1974. (Photo: Pierre Manevy / Express / Getty Images)

Ironically, the tangible results of the actual crime had only a very modest impact. There was virtually nothing of value obtained through the wiretaps the burglars had installed in the Democratic Party offices.

Nonetheless, the vastly larger repercussions of the break-in continue into the present as they helped to significantly degrade national trust in government leaders.

In fact, the current congressional hearings are an effort to address public understanding about the failed insurrection of 6 January 2020. On that day, after it was abundantly clear that Donald Trump had been decisively defeated in his bid for reelection, he had convened a mob and egged it on to seize the Capitol Building to halt the formal, ceremonial certification of Joe Biden’s election as the next president.

But that act also has tendrils that reach back to that earlier Watergate break-in.

Fifty years ago, on the evening of 17 June 1972, a small team of men (who gave their occupations as “anti-communists” when they were booked by the police who arrested them) broke into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee. Those offices are very roughly analogous to Luthuli House, but with far less authority and power than the ANC’s headquarters holds in South Africa.

That office was in the swanky Watergate office block/luxury hotel/apartment complex in the Foggy Bottom neighbourhood of Washington, DC. Actually, this was the second effort to plant a listening device in a phone in the DNC offices, but that first effort had gone undetected.

Their mission had been to place wiretaps on the desk phones of top DNC officials, photograph confidential office files, and, presumably, install eavesdropping devices in conference rooms to catch all the “good stuff”.

Several other operatives with a direct tie to the White House had stationed themselves across the street in what was then the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge, where they could see the DNC office windows so that they could monitor the progress of the caper, and also so that they could maintain a lookout for the arrival of any building guards or the police.

An exterior view of the Watergate Hotel in Washington, DC which contained the headquarters of the Democratic National Party. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

At first, the plot seemed like your basic burglary gone awry — with overtures of a comedic gangster film like The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight.

The whole effort came to an abortive end, however, when a security guard noticed a strip of adhesive tape had again been placed over the office’s door lock after he had removed an earlier bit of tape placed there by the burglars. That second piece of tape impelled him to call for police back-up to deal with what was initially assumed to be just a common burglary.

The initial report in the Washington Post, written by longtime police reporter Alfred Lewis on 18 June 1972, began with the words:

“Five men, one of whom said he is a former employee of the Central Intelligence Agency, were arrested at 2:30 a.m. yesterday in what authorities described as an elaborate plot to bug the offices of the Democratic National Committee here. Three of the men were native-born Cubans and another was said to have trained Cuban exiles for guerrilla activity after the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion. They were surprised at gunpoint by three plain-clothes officers of the metropolitan police department in a sixth floor office at the plush Watergate, 2600 Virginia Ave., NW, where the Democratic National Committee occupies the entire floor.

“There was no immediate explanation as to why the five suspects would want to bug the Democratic National Committee offices or whether or not they were working for any other individuals or organizations…

“The early morning arrests occurred about 40 minutes after a security guard at the Watergate noticed that a door connecting a stairwell with the hotel’s basement garage had been taped so it would not lock.

“The guard, 24-year-old Frank Wills, removed the tape, but when he passed by about 10 minutes later a new piece had been put on. Wills then called police.”

Follow-up stories began featuring the shared byline of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, the two reporters who, more than anybody else, would go on to unwrap the scandal that ultimately led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

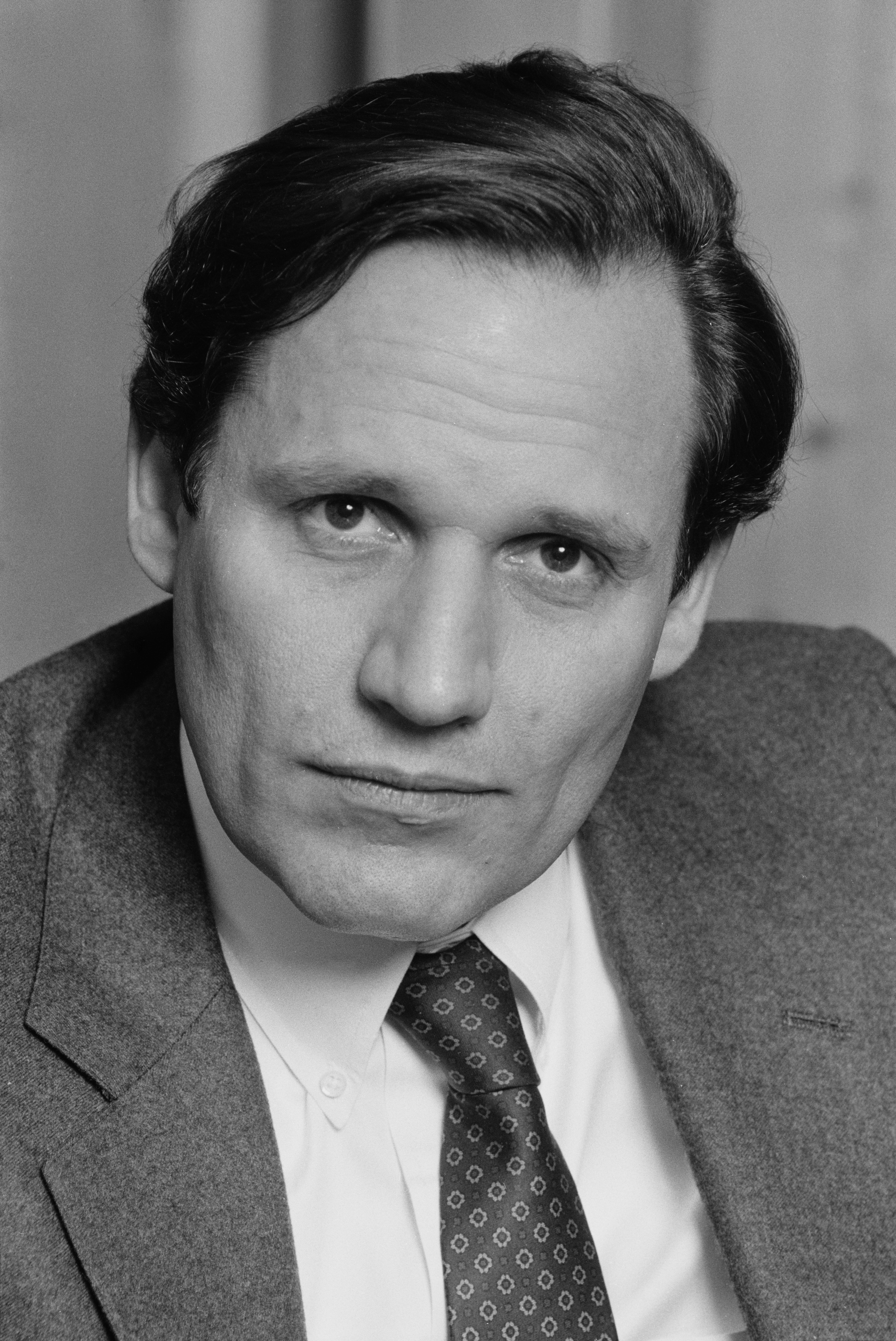

American investigative journalist Bob Woodward in 1985. He reported on the Watergate scandal in the 1970s while working for The Washington Post. (Photo: Steve Wood / Express / Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

The story first began unravelling once a connection between the burglars and individuals operating within White House offices (and incumbent president Richard Nixon’s reelection committee) became apparent through a notation in a personal address/phone book that identified a contact for the burglars, with the incriminating initials WH after his name.

The journalistic pairing of Woodward and Bernstein went on to become what was, arguably, the most famous (and consequential) reportorial team in history.

Bob Woodward (right) and Carl Bernstein speak to members of the media from the steps of Woodward’s house in Georgetown, Washington DC on 1 June 2005. (Photo: Win McNamee / Getty Images)

Over the next two years, “Woodstein” — as their editors sometimes called them, so closely did they work together, despite different backgrounds, life histories and working styles — broke scoop after scoop in getting the details of the Nixon administration’s criminal actions that had spun out of what Nixon’s 1972 re-election committee chairman John Mitchell (and former attorney general) had dismissively called a third-rate burglary.

The reporters’ diligence ultimately led to an unprecedented presidential resignation in disgrace from office in August 1974. And these two reporters (although, increasingly they were just the leaders of a growing pack of “hounds chasing the fox”) largely did their work the old-fashioned way. They wore out their shoe leather, as the phrase goes, in their dogged persistence in chasing down leads.

They banged on doors at night to speak with recalcitrant, but potentially important, sources; they slogged through massive piles of documentation of financial records to “follow the money”, as one of the characters in the movie made about them had said; and they waded through mounds of records of books borrowed from the Library of Congress to suss out the organogram of the White House, to identify who worked for whom in a network of illegal acts.

Senate committee hearings

As special Senate committee hearings began grinding through testimony and documents; as special prosecutors were appointed to lead the investigations, and as some justice department leaders resigned or were fired rather than rein in those special prosecutors, a metastasising spread of political and financial criminal misbehaviour came to light.

In an unexpected, yet dramatic moment, the heretofore unknown (to the public or Congress), voice-activated taping system installed in the Oval Office in the White House was accidentally revealed by a minor White House aide, Alexander Butterfield.

This knowledge fuelled an increasingly frenzied search for the “smoking gun” of presidential complicity in the tangled mess the scandal had become.

Eventually, John Dean, the young legal counsel to the president, effectively switched sides. In his Senate testimony, he told the hearings he had advised the president there was a cancer growing on Nixon’s presidency — implying the cover-ups occasioned by the Watergate break-in had unleashed a growing disaster.

Incredibly, many of the successive revelations were now taking place, live, on national television, casting a harsh light on how the Nixon White House had been organised and how it had acted much like a mythic mafia family. But that was a family where the capos and soldiers were dressed in pressed, white, button-down shirts, bland ties and remarkably unremarkable suits, rather than the flash attire favoured by gangsters — at least in the movies and on television.

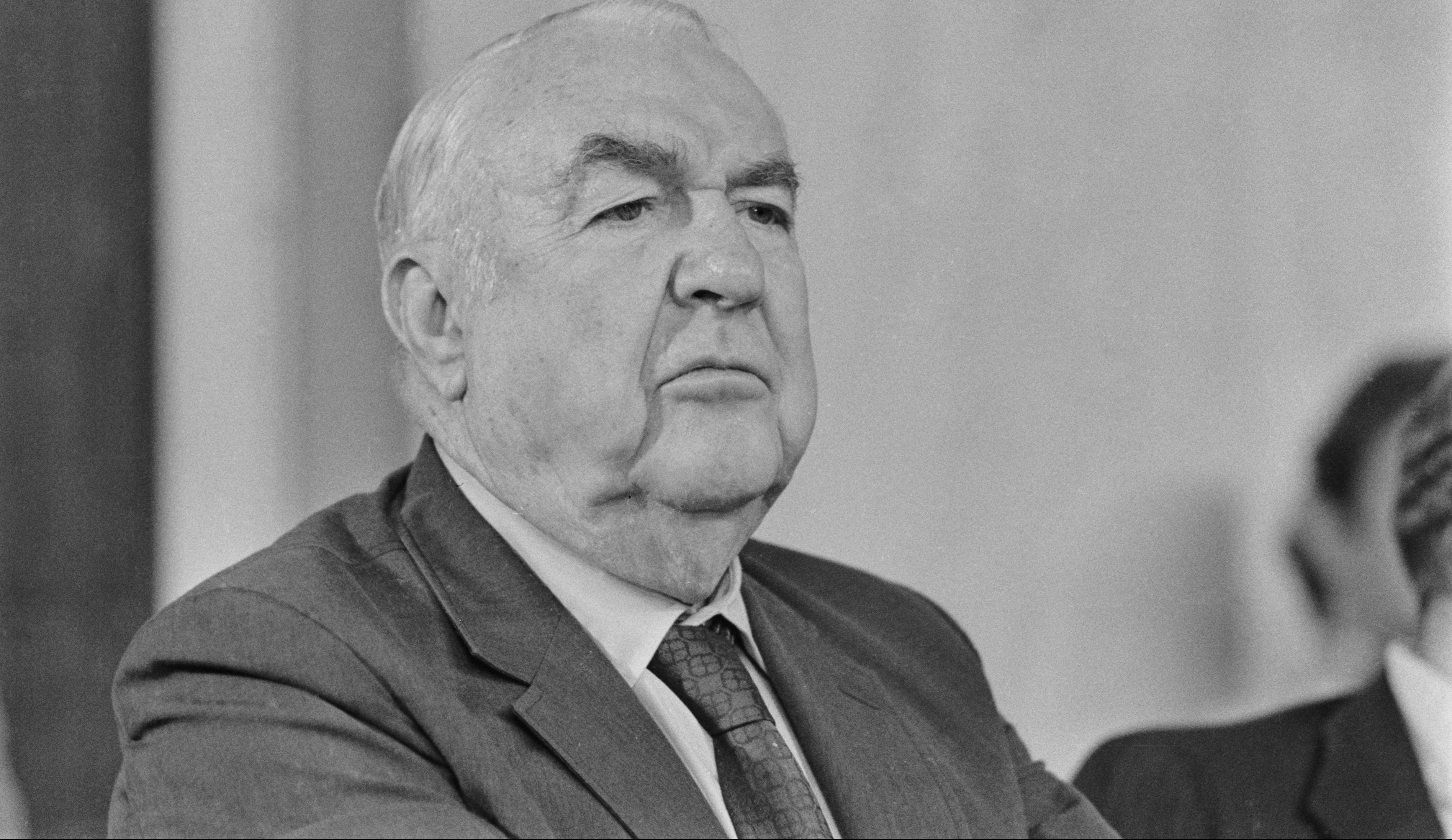

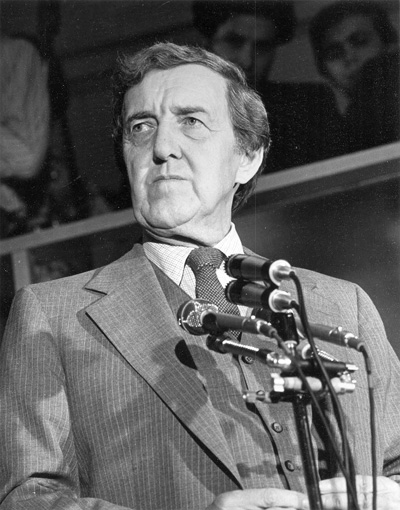

Sam Ervin (1896-1985), United States Senator from North Carolina, during the Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities hearing, established to investigate the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex, held at the Capitol Building in Washington, DC, in 1973. Ervin, a Democratic Party member of the committee, also served as its chairman. (Photo: John Downing / Daily Express / Hulton Archive / Getty Images)

The testimony extracted from aides who had been called to account for themselves came initially at hearings chaired by North Carolina Democratic Senator Sam Ervin. Ervin had almost gleefully called himself “just an old country lawyer”, embracing his role of a lifetime as a defender of the rule of law, the US constitution, and public morality — as he proceeded to verbally eviscerate hapless Nixon staffers, live on national television.

With the revelations from Woodward and Bernstein’s (and the others’) reporting, those exposés demonstrated the truth of the aphorism — popularised by the Watergate scandal — that “the cover-up was worse than the crime”.

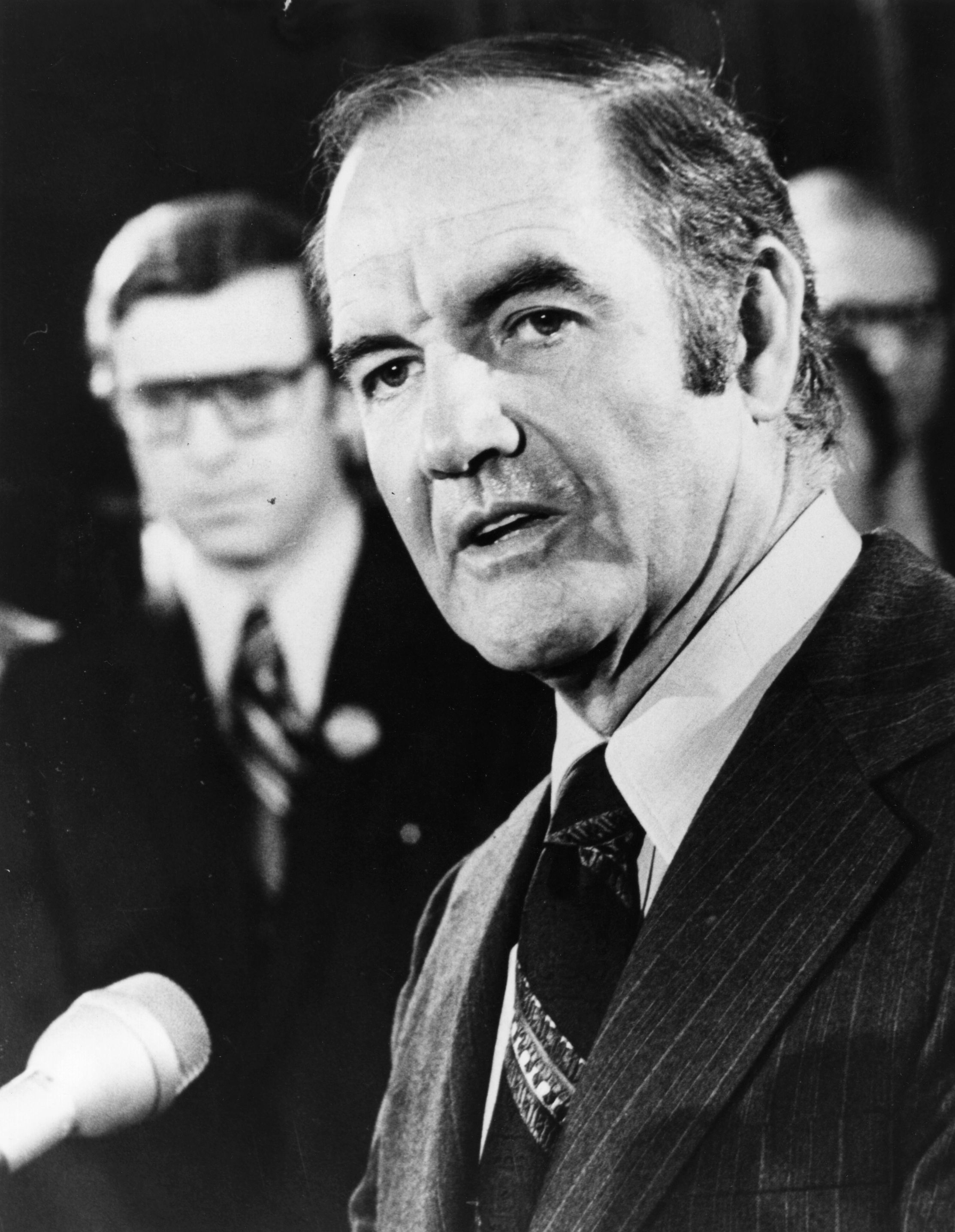

American Democratic politician and candidate for the 1972 presidential elections, Senator George McGovern. (Photo: Keystone / Getty Images)

The irony, of course, was that the trigger for the whole mess — the break-in and wiretapping — was that any information that might have been gleaned from a working wiretap was virtually worthless in revealing anything “useful” about the already doomed candidacy of Democratic Senator George McGovern to become the US president in 1972.

Eventually, the clamour for Nixon’s resignation became unstoppable on the part of Democrats and then, critically, most of the Republican congressional delegation as well.

The trigger came as the president had very reluctantly authorised the release of transcripts of key conversations from those White House tape recordings. However, the transcripts largely left out more than 18 minutes of crucial conversations that would have included direct presidential instructions to his aides to carry out what would have to have been seen as criminal acts.

The press had a field day mocking the White House’s increasingly frantic yet unbelievable denials, especially after photographs were released by the president’s office purporting to show how Nixon’s secretary, Mary Rose Woods, had “accidentally” deleted those crucial minutes while she was in the act of transcribing the tapes.

Nevertheless, the damning instructions eventually saw the light of day with a previously unknown tape that demonstrated the president’s direct knowledge and approval of efforts to hush up the burglars’ connection to the White House.

Part of the transcript of that tape had HR Haldeman, the president’s most senior advisor, explaining to the president the cover-up plan, saying, “the way to handle this now is for us to have Walters [CIA director] call Pat Gray [FBI director] and just say, ‘Stay the hell out of this… this is, ah, business here we don’t want you to go any further on it’.”

Resignation

Soon enough, a delegation of senior Republican senators then met Nixon to inform him his resignation was imperative as he had virtually no support left among Republicans in Congress, let alone among Democrats.

His impeachment would prevail in the House of Representatives and that, in turn, would be followed by his conviction by the Senate.

Marking this 50th anniversary of the crisis that began with the break-in, the Associated Press summed it up, saying that the initial crime had steamrollered into a “… scandal that led to the resignation of the Republican Richard Nixon as U.S. President on 9 August 1974. He was accused of misusing govt agencies including the FBI, the CIA and the Internal Revenue Service in attempting to cover up the scandal and a total of 40 govt officials were either indicted or jailed. In 2005, former FBI deputy head Mark Felt was revealed to be the anonymous source codenamed ‘Deep Throat’ who helped Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein to uncover the Watergate affair. ‘Gate’ has since been suffixed to any major political scandal”.

Shattered by the outcome of that crucial meeting with Republican senators, Nixon resigned shortly thereafter, fleeing into a domestic exile in California where he slowly rebuilt his public presence as a strategic thinker on global issues until his death in 1994. (This act of creative reinvention proves, as nothing has ever done before in America so successfully, that there is always a chance for redemption by moving west, shucking the tired old rags, and beginning fresh, anew.)

How did this extraordinary crisis originate and what have been its effects on our present circumstances and on into the future? The answer to the first question must draw upon roots in 20th-century American history and political life and ideas. For the second, the circumstances are now taking on a kind of extraordinary second life, in light of the ongoing hearings by a select committee of the House of Representatives, focusing on the insurrection of 6 January 2021, and the role of the then president in directly precipitating that crisis.

The origins

The immediate origins of the Watergate crisis of 1972-4 had been set in motion after Richard Nixon determined he would run for a second four-year term of office. He had won his first term in 1968 in a bitter campaign against Vice President Hubert Humphrey, the man who had taken on the leadership of the Democratic Party after President Lyndon Johnson, who had faced bruising challenges from Senators Robert Kennedy and Eugene McCarthy, and had then taken himself out of the running for a second full term.

Johnson was, of course, also facing a deep, growing national unrest against an unending Vietnam War, as well as the tide of civil strife in many of the nation’s cities following the murder of the country’s leading civil rights figure, the Rev Martin Luther King Jr.

Humphrey’s own 1968 nominating convention in Chicago was battered by running street battles between anti-war demonstrators and that city’s police force, as well as an obscene truculence from the city’s mayor, Richard J Daley, all nationally broadcast.

Humphrey’s candidacy was further assailed by a revolt among long-time conservative, white Southern Democratic voters, increasingly resentful of both civil rights legislation and protests.

Many such voters turned to a third-party candidate, the arch-segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace, who gained the majority of votes in nine Southern states, as well as among significant numbers of nominally Democratic white voters in the Northern and Midwestern states. That helped ensure those states went into Nixon’s column in the electoral vote contest. Nixon won a tense victory, even though, in the end, only a half million popular votes separated Nixon and Humphrey.

Then, as the 1972 general election began to come into focus, Nixon’s aides were scrutinising the jockeying for the Democratic nomination for president, trying to game who would be the strongest opponent against Nixon.

Crucially, they also began scheming how they might upset that individual’s chances, ensuring Democrats would field a weaker candidate.

Former United States Secretary of State, Edmund Muskie. (Photo: Wikipedia)

At that point, the smart money was that Maine Senator Ed Muskie would be the strongest individual. He had acquitted himself well as Humphrey’s running mate in 1968, and he had a reputation for personal probity as well as an understanding of the challenges of foreign policy.

On that basis, from the early days of the 1972 Nixon re-election campaign organisation, the Committee to Re-elect the President — bearing the eerie acronym, CREEP — using deniable cut-outs and backchannel and illicit fundraising mechanisms, began carrying out “dirty tricks” to throw the Muskie effort into disorder.

These ranged from the borderline comic to the venal. The final straw was spreading vicious, false rumours about Muskie’s wife, which led to a widely reported event where Muskie was seen with tears streaming down his face as he denounced those rumours and those who would purvey them. Presidents and would-be presidents never cry, however, was the lesson drawn.

The Nixon team’s intention had been to so disable the Muskie campaign that a much weaker candidate, someone like South Dakota Senator George McGovern, would emerge instead, once the Muskie campaign had collapsed.

McGovern had been a genuine World War 2 combat hero, an experienced foreign aid administrator, and a veteran senator with expertise in both foreign policy and agricultural issues, but his anti-Vietnam War position could be twisted into an easy-to-attack, weak, unpatriotic one by Nixon’s minions.

Doomed campaign

As it turned out, Senator McGovern’s campaign was practically doomed from the start. There was dissension inside the campaign over tactics and policies, as well as a flawed selection of a running mate that required replacing Senator Thomas Eagleton with Sargent Shriver, the former head of the Peace Corps, once Eagleton admitted he had undergone psychiatric treatments, including electroshock therapy, earlier in his life.

Given McGovern’s doomed candidacy, it was bizarre the Nixon re-election campaign even contemplated a burglary and placement of illegal listening devices and wiretaps in the DNC, given Nixon’s re-election was on track for a landslide victory.

But, as David Gergen, a man who had served as a senior aide for four different presidents (two Democrats and two Republicans) said on CNN recently, while Richard Nixon was a man of great strategic gifts, he also housed uncontrolled, even uncontrollable, demons within himself.

As a result, in his White House and in the re-election campaign mechanism, he had installed — and then unleashed — conscience-less men who believed they were beyond the law, whether it was in authorising break-ins into his competitor’s offices, raising a vast flood of tainted campaign contributions well beyond legal limits, or using such cash to underwrite illegal campaign acts.

All this went hand-in-hand with the Nixon administration’s wholehearted embrace and enlargement of the ongoing Cointelpro initiative, a government counter-intelligence effort aimed at finding the sources of foreign support for anti-war and civil rights activism. (They never actually found any support or sponsorship.)

The Cointelpro initiative drew in elements of the FBI and the CIA in what became an illegal domestic spying initiative — and, as such, it also served as an inspiration for other domestic eavesdropping such as the planned Watergate break-in.

Irony

As we mentioned, the irony of the Watergate break-in was there would be virtually no useful information to be gained from such wiretaps. The McGovern campaign was largely headquartered in another downtown office suite and, in any case, the McGovern campaign was already mired in its self-inflicted meltdown.

By the time the scandal wound up, the president had resigned (and been pardoned by his appointed successor, Vice President Gerald R Ford, after Nixon’s original running mate, Vice President Spiro Agnew had earlier also resigned over acts of bribery while he had been governor of Maryland and a county administrator).

Meanwhile, by the end, dozens of Nixon aides had been indicted or sentenced to prison terms and fines. Some, like Charles Colson, eventually became a prison rights advocate and lay minister while in jail, while John Dean eventually rehabilitated himself sufficiently to become a best-selling author and widely sought-after “talking head” on television, analysing political issues.

All the President’s Men

In the process, Woodward and Bernstein had written their phenomenal best-seller, All the President’s Men, published even before the final demise of the Nixon presidency. Those last events were profiled in their next volume, The Final Days.

The two reporters’ efforts were then turned into an equally extraordinary film, directed by Alan J Pakula, starring Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman — the whole cinematic effort Redford had been tirelessly behind from the beginning.

In contrast to the book, since the outcome was now known, the denouement in the film’s final minutes came through a series of newspaper front pages and stories being typed (typewriters were still in general use) as the news advanced through to Nixon’s final humiliation.

The two writers’ careers continued to bloom for decades, producing an entire shelf of reportage on national politics, jointly or separately. Further, their reportorial effort inspired two generations of young people to become journalists — and most especially to take on the rewards and challenges (and difficulties) of investigative journalism.

Distrust in government

There was another side to this success, however. Even before Watergate, many Americans were already becoming increasingly less disposed to trust official pronouncements.

One major shift had come via the circumstances of American military “success”, or the reasons for the initial intervention in South Vietnam — or over the still darker secrets of bombing runs in the North, or over neighbouring Laos or Cambodia in the 1960s and early 1970s.

The revelations of the duplicity and criminal excess by the Nixon administration in its workings simply compounded the deeper problem, making it that much more difficult for citizens to trust government leaders or take them at their word.

Into the present, a default setting, even now, is an assumption of distrust by many that virtually any government statement (think the corrosively cynical rhetoric about a “deep state”, or the supposed dark secrets of Covid vaccines, and the “truth” of QAnon, or even older revelations about such things as the appalling Tuskegee syphilis experiment) is unlikely to be the truth.

Of course, it is true that a guarded suspicion towards the actions of a government can be a healthy thing. Governments can, obviously, carry out mistaken or malevolent practices, and it is vitally important they be exposed.

But, combined with all those other prevarications and depredations on the truth, the relationship between the governors and the governed has suffered a wound that has never been healed.

This condition or climate of distrust in government has another stream of history in the growth of the disaffected who have, over the past half century-plus, embraced the ideas of radical, conspiratorial movements — attitudes identified by social historian Richard Hofstadter in his 1964 article, The Paranoid Style in American Politics.

Hofstadter wrote:

“American politics has often been an arena for angry minds. In recent years we have seen angry minds at work mainly among extreme right-wingers, who have now demonstrated in the Goldwater movement how much political leverage can be got out of the animosities and passions of a small minority.

“But behind this I believe there is a style of mind that is far from new and that is not necessarily right-wing. I call it the paranoid style simply because no other word adequately evokes the sense of heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy that I have in mind.”

Feeling left out or left behind by the rest of the nation, early in the 21st century, such people were natural supporters of the “Tea Party” movement, eventually becoming the core for Donald Trump’s most devoted disciples.

Hofstadter had concluded his analysis, saying:

“Having no access to political bargaining or the making of decisions, they find their original conception that the world of power is sinister and malicious fully confirmed. They see only the consequences of power — and this through distorting lenses — and have no chance to observe its actual machinery.

“A distinguished historian has said that one of the most valuable things about history is that it teaches us how things do not happen. It is precisely this kind of awareness that the paranoid fails to develop. He has a special resistance of his own, of course, to developing such awareness, but circumstances often deprive him of exposure to events that might enlighten him—and in any case, he resists enlightenment.

“We are all sufferers from history, but the paranoid is a double sufferer, since he is afflicted not only by the real world, with the rest of us, but by his fantasies as well.” [Emphasis added].

As we are now learning from the ongoing House of Representatives’ Select Committee hearings on the 6 January insurrection — and specifically the role of Donald Trump in fomenting it to thwart the legal transfer of power on 20 January — it seems clear Trump was negatively afflicted by the events of the real world, but also by those fantasies his aides and even family members had been singularly unable to disabuse him from holding.

The result has been yet another political tragedy.

The current congressional committee is carrying out its televised hearings, just as those earlier committees did during Watergate. Now they are attempting to re-establish the possibility of trust in government by a majority of the nation’s citizens.

But, this time around, it will be even harder than it was back in the 1970s. Chalk up the need for this as yet one more outcome of the Watergate crisis from 50 years ago. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

At least Nixon managed to do something worthwhile as President by opening up China. This strategy was intending to bring China in to world trade and away from Russia, and had been successful until Trump picked a fight with China , on an ignorant and superficial whim, driving it back into alliance with Russia. I suppose you could say that one of the differences between the two was that Nixon was strategically smart but had his demons while Trump was strategically thick and was demonic.