Tribute

John Berks — the ‘Boykie’ who changed South African radio

John Berks was key to bringing talk radio to South Africa, changing the country’s broadcast world forever. He’s gone now, but he casts a great legacy.

Back when John Berks was the king of morning radio, people would tell the story about the times when commuters driving in their automobiles, simultaneously pulling up to a red traffic signal in different cars, with all of them laughing in their separate cars, giving each other thumb’s up signs so everyone at the traffic stop would know that they were all listening to another bit of Berksian broadcast mayhem. Or, as one of his 702 colleagues, Aki Anastasiou, said of Berks on the airwaves, “He created the most authentic theatre of the mind experiences for his listeners.”

Berks came out of the West Rand mining towns of Klerksdorp and Krugersdorp, but, early on, he felt the magnetic tug of radio and the big city, and he knew he was destined for them. After leaving high school, but before he broke into radio, he had worked in a soap factory and then as a junior reporter at the Germiston Advocate newspaper, until he finally passed an audition for LM Radio. “Berksie,” as he was often called by friends and admirers, or sometimes, as he was called “Long John Berks” as well, eventually moved to Joburg to become programme manager at LM Radio. Along the way, he had also worked for Swazi Music Radio, Springbok Radio, Capital Radio, 604 Transkei, and Radio 5.

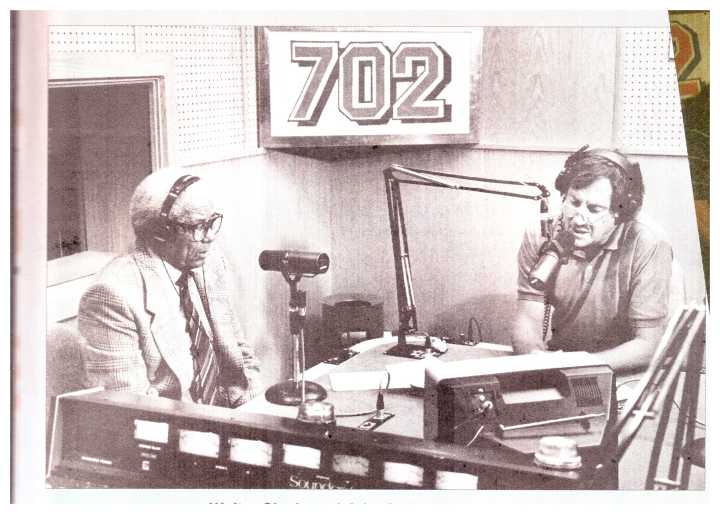

But the move that made all the difference was when he moved to Radio 702 in 1981, where he soon became its most popular on-air voice. He finally left 702 in the early 90s for what became a virtually never-ending sabbatical, but he did return for one last spin of the dial for a stint as co-presenter on “The John and Gary [Edwards] Show.”

But back when Berks was still a teenager, one of his high school teachers, thoroughly unconvinced about Berks’ future success in life, had told him at the end of the school year that he, the teacher, was certain they would meet again, but it next would be when the instructor was riding a train, and Berks would be the man walking through the carriages, punching riders’ tickets. Despite that dismissive judgment, broadcasting’s legend-to-be proved his teacher to be a poor judge of predicting Berks’ career trajectory.

But it was Berks’ move to 702 (so named because of its broadcast frequency on the AM band) that made the big difference for his impact on South African radio. Increasingly convinced an AM station could not match the sonic quality of an FM station with the latter’s interference-free sound quality music listeners wanted to hear, together with the station owners, Berks was instrumental in bringing the talk radio format to South Africa.

Talk radio had become well established in the US on a plethora of commercial radio stations. Berks, in his visits to the US, including mandatory meals at the late, lamented Carnegie Deli, became convinced the talk radio format should be a key part of South Africa’s radio future. Convinced, the station’s managers began recasting their station’s profile, increasingly transforming it into a talk radio format for the various time slots, Monday through Friday. Meanwhile, Berks soon took over the weekday morning rush-hour show. Weekends on 702 still offered broadcasts of contemporary popular music, Broadway classics, and progressive and classic jazz shows.

Previously, South African radio broadcasts had largely been music programmes (with nothing too controversial or anti-establishment, of course), including a music show — “Forces Favourites” — on the government broadcaster, playing requests and messages from soldiers’ girlfriends, wives, and families for men who were serving “at the border” (a euphemism for fighting in Namibia or Angola). There were also radio dramas, government propaganda cleverly disguised as news, and sports broadcasts.

Broadcasts were effectively segregated in accord with the government-defined race and language groups, and the several African vernacular language broadcast channels offered a diet of music and family life dramas, much of it designed to encourage listeners to think longingly about those old, traditional, tribal ways, back in those so-called homelands, as opposed to the more problematic life of the big cities.

Meanwhile, English and Afrikaans language streams aimed at white listeners featured serials of cops-and-crooks stories. The morning rush hour shows mixed music, a bit of polite chatter, news headlines, and the weather. And, if you were an early riser, you could listen to farm reports, usually filled with sage advice about crop planting, long-range weather forecasts, and predictions on prices of commodity futures.

By contrast, once Berks fully developed his morning show, his unique blend included non-stop, clever patter and his inimitable prank calls. (Listen here to Berks masquerading as Peter Ndlovu, telephoning the actual Pik Botha to ask him to come to Soweto to cook potjiekos — the traditional meat stew over an open fire made in a large, cast-iron pot — for members of the Dobsonville, Soweto chapter of the ANC Youth Club.

Berks’ stories were delivered in his inimitable voice and style, gently taking the Mickey out of somebody important. Together with news, traffic reports, sports and weather, Berks’ blend of material captured listeners’ ears, and his broadcasts outpaced the much stodgier competition from the national broadcaster.

702’s former station manager, Yusuf Abramjee, said of Berks’ impact, “He was radio. John kept me glued to the radio from a young age. His prank calls were simply the best. He made 702 what it is today. When I was station manager, we decided to bring him back to host a weekly music show.… In 2010 John received the Lifetime Achiever Award from the Radio awards.”

His long-time broadcast colleague, Jenny Crwys-Williams wrote to this writer to talk about Berks’ impact and legacy to say, “John Berks was hugely successful as a DJ. He had the voice, good quips, great music and in culture-starved South Africa, LM Radio attracted only the best. And Berks was one of them. And then came the move to a small Joburg-based music station where there was no end of rock ‘n roll ambition just aching to expand into the big time. There was just one problem: 702 streamed its music on an AM signal.

“Anyone behind a microphone and broadcasting music on an AM signal will know that it’s impossible to compete with better-endowed radio stations with an FM signal. No weather interference, no crackling, no storms playing it out on air. And the highveld has big storms. So while 702 had an enthusiastic audience and restless DJs straining at the leash, let alone entrepreneurs like Stan Katz and Rina Broomberg pushing radio boundaries on an almost daily basis, there was just a limit to what they could do. In the meantime, Berksie was travelling to the States almost as often as night following day.

“Out of his trips in the early 80s eventually came one great idea, talk radio, US-style, of course. He loved everything to do with the USA, the wisecracks, the humour, the snappy delivery, the showbiz interviews. It had John Berks written all over it.

“So when he came home, [it was] to the sounds of the SABC and ‘Squad Cars.’ At what stage the owner of Channel 702, Issie Kirsch, was persuaded to go with Berksie’s talk radio idea is not clear, but legend has it there was a coven of Berks, Stan Katz, Rina Broomberg and a bottle of whisky. By the time it was finished, it was a done deal. Not that music would disappear overnight. Talk would sort of sidle into the mix, accompanied by sport, a growing news department and a bit of finance.

“On June 28 1980 talk radio came to South Africa…. But right from the beginning of 702’s entry into talk African-style, Berks was the superstar. There could only be one. His gift for mimicry, his understanding of small-town humour, his irreverence, his instinctive sense of comedic timing (but a supreme indifference to the timing of spot breaks and news) made him an entertainment legend. People began talking about 702.

“In spite of the welter of talent on 702, Berks continued to straddle the station. He earned big and his homespun humour grew. Perhaps his best-known call was the one where he imitated Ronald Reagan.

“Even now that one has real freshness and humour in it.

“It’s fair to say, though, that 702 was made as it continued to morph from part talk to all talk thanks to the changing times. The struggle was writ large. Leading the news charge and demanding more and more time was news maestro Chris Gibbons; John Robbie moving adroitly from sport to ‘Talk at Nine’ and mesmerising everyone with his combative passion, fearless, and, famously, Judith Dubin, also in the newsroom, standing close to Chris Hani’s body and reporting the news of his assassination to a horrified audience.

“As always when times are tough, humour helps soothe fears and heartbreak, and John Berks rose to the occasion, day after day. But it took its toll and when John eventually took himself off air into a sabbatical that, more or less was permanent, Gauteng lost a talent that, even today, remains unmatched.”

John Robbie, the broadcaster who eventually followed Berks on the morning shift, upon learning of Berks’ passing, wrote, “His gift was humour and irreverence in an age when, even that, was seen to be rebellious. [He was] a friend and a mentor and a legend.” Robbie added, “Berksie always found reasons to go to America and he loved America and he always found a reason to do the research. He said one of the things he found was that they would get sports stars to do guest reports and somebody asked who could do it. That’s how it all started [for Robbie].”

This talk radio format, as it expanded into the rest of the broadcast day, complete with its open line features and live — and increasingly lively — debates on air, brought about an entirely new and vibrant dimension to South Africa’s political and social discourse. Radio 702 became an integral part of the country’s rapidly evolving political dialogue.

A key part of the allure of the new formula was the possibility that people of all backgrounds, ethnicities, races and political affiliations felt increasingly free to express their opinions about the country’s biggest challenges and issues via 702’s platform, whenever they called in. This new world of broadcast radio made the station mandatory listening for foreign journalists and diplomats as well, in the heady days at the end of the apartheid era, the beginnings of negotiations, and then on to the country’s non-racial democratic order. Although Berks’ own morning show was not ground zero for the emerging, hard-driving national political debate, his free-wheeling, irreverent, say-virtually-anything style on air encouraged and reinforced the station’s other broadcasters to run with that national conversation in their interactions with listeners.

By the time Berks left the airwaves, he had become, in those sometimes overused phrases, both an icon and a legend — and a touchstone for newer, younger broadcasters to model themselves. Gushwell Brooks, a later addition to 702’s stable of broadcasters, described his relationship with Berks, saying, “My grandmother worked as a domestic worker in Vereeniging and I, along with my parents — illegal under the Apartheid Group Areas Act — lived in the garage which belonged to the white family my grandmother was employed by. Nonetheless, one of the most lingering memories I have from those first four years of my life, was John Berks’ voice on 702.

“In June 2011, at the age of 29, I got my break and started my first and only radio gig on the very same platform I listened to on an AM signal, 702. Being the longest job I’ve ever had and still have, I have had some amazing conversations, but amongst the most amazing moments of my radio career was when I had the unbelievable privilege of meeting and interviewing John Berks on Sunday the 14th July 2019 and once more in celebration of 702’s 40th anniversary, on the 28th June 2020…. His passion for radio, the joy it gives, how it informs, how it simply entertains and how he played a central role in bringing that to life, is what gave life to John Berks.”

Anthony Fridjhon, the well-known actor and voice-over artist said of Berks, upon hearing of the broadcaster’s passing, that his was “a voice made for radio, his mimicry was legion, the characters he came up with were brilliant. Together with many, I will miss him. ‘What a Boykie!’” What else could we add? DM/ ML

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9591″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Great memories. Thank you

While a boarding school in the 60’s we had to use shortwave radios to listen to John Berks on LM radio. As boys locked up at school we loved his ‘subversive’ persona – he presented the LM hit parade as well. I still remember his introduction to his show (in his version of Afrikaans): “Jukkel, stukkel, lekker, lekker leks. Ek is ‘n Gé en ek is bly”. Howzit my Chinas!” For those younger folk, a gé is SA slang from back then that refers to a disreputable individual “who drives around with fur on the dashboard of his car and a plastic orange attached to the top of his car’s aerial”.

Great article, brought back so many memories. Rest in peace John Berks!