CAUSE AND DISASTROUS EFFECT

Early warning systems on floods are not enough; climate crisis literacy saves lives – experts

The extreme rainfall and floods that hit KwaZulu-Natal in April highlight the importance of the relationship between the government and residents.

‘If we had told you there was this major flood coming, what would you have done differently?”

This was the question Geoff Tooley, senior manager in the Coastal Stormwater and Catchment Management Department at the eThekwini Municipality, wants to pose to South Africans following the devastating floods in KwaZulu-Natal in April and May.

The South African Weather Service – the only mandated regulatory body that can issue weather warnings in the country – provides a three-day rainfall forecast to municipalities every 12 hours.

This information goes into eThekwini’s Forecast Early Warning System (FEWS), which then runs hydraulic models, says Tooley. The system highlights whether critical points where there is a risk identified by the municipality – such as informal settlements on floodplains, substations prone to flooding and roads that can be overtopped – are likely to be exceeded.

This is shared with the disaster management team which has SMS communication systems with residents and also uses social media to issue localised information on the back of weather service warnings.

The radar and rain and stream gauges are used to verify storm cells forecast by the models, and to provide real-time information to the team about what is happening in the field during the storm.

But, as climate scientist and contributing author on several Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports Francois Engelbrecht told Our Burning Planet, “we have to admit that whatever we think we have in place failed, because almost 500 people died – even in one of our municipalities that are most aware of climate change risks.

“We have to reflect: where did things go wrong?”

What Tooley is getting at is that the warnings were there, but what isn’t always there is climate hazard literacy – people’s understanding of what to do when these disasters strike.

Engelbrecht agreed that sometimes early warning systems are not enough – as illustrated in his research paper that explored how accurate early warnings were not enough to prevent the immense tragedy of the Beira flooding in Mozambique in 2019.

There was a lot of evidence that the Mozambique government did issue warnings of the coming storm, but not the understanding of what this climate risk would mean.

Using the Quarry Road informal settlement as an example, Tooley illustrated during the sixth meeting of the Presidential Climate Commission (PCC) on 27 May 2022 that having strong partnerships between the government and communities on the ground can help prevent loss of life and prepare people for climate disasters.

A community-based early-warning system was implemented when the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) began engaging with Quarry Road residents in 2014.

The settlement, established in the late 1980s, has 1,070 informal houses on a narrow floodplain of the Palmiet River, making it prone to frequent flooding after heavy rain and therefore highly vulnerable to socioeconomic and environmental risks.

Tooley said all of eThekwini’s informal settlements within floodplains are mapped and the municipality takes note of river crossings that are susceptible to flooding and other key infrastructure aspects that are at risk.

“All this information is useful,” he said during the PCC meeting. “But if we can’t get it into the community’s hands so that they can respond, it is really ultimately useless.”

eThekwini’s Forecast Early Warning System highlights the crucial points where flooding could be a risk. (Source: Bahle Mazeka School of Built Environment and Development Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal)

UKZN researchers trained 35 community-based researchers at Quarry Road who developed hazard maps for their settlement, identifying escape routes where the water would flow and where the high-risk areas were.

Cathy Sutherland, a professor in the School of Built Environment and Development Studies at UKZN who is part of the Quarry Road project, said focusing on the co-production of knowledge allowed them to come up with new ways to address climate challenges in cities.

“You’ve got to focus on building knowledge and understanding, not just transferring knowledge into communities,” she told Our Burning Planet.

“Communities have a lot of good knowledge of their own, which they can share with you and teach you. We have to focus on co-producing knowledge and valuing community-based knowledge much more.”

Sutherland said the interface between scientific knowledge from researchers, weather monitoring from the municipality and community-based knowledge made the response to climate disasters a lot more powerful.

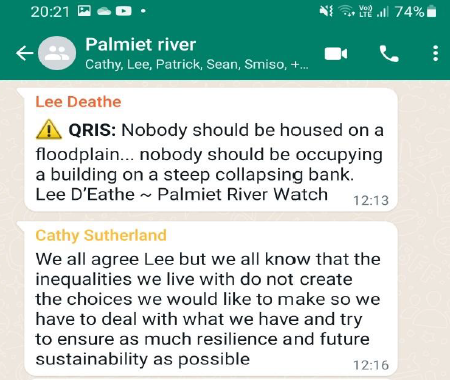

In the case of Quarry Road, after the disaster management team receives the information from the FEWS team, City officials, UKZN and NGOS liaise with community leaders on WhatsApp groups who have systems in place to disperse alerts to residents. The latter then provide live updates in a feedback loop.

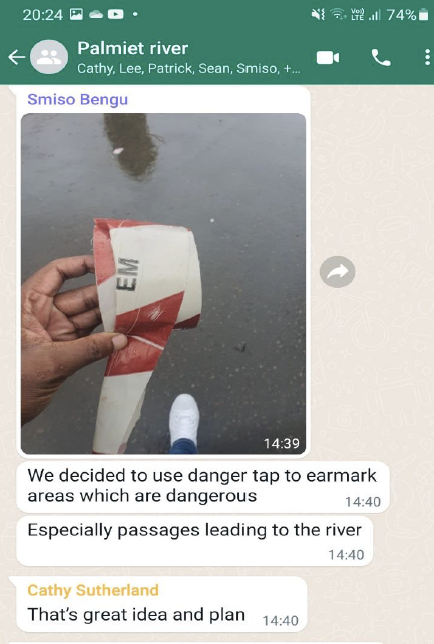

On 11 April 2022, at midday when the river levels were rising, community leaders put up red warning tape along the river’s edge to keep people away from the banks and to alert them that things were changing.

In the afternoon residents in some areas were warned to evacuate and move to higher ground since the pressure system would pose flood risks to their area in the evening.

Sutherland said this was difficult because the open space to which they typically evacuated was full of houses and the river changed course, thuse taking out the usually safe place where people had put all their belongings.

“People were very scared as they did not know where to go as it was dark. There was load shedding too and also the river had changed course so I was telling them to go to a petrol station I know and they were going to places where there was some higher ground.”

Informal dwellings at risk of collapse on the banks of the Palmiet River on Monday 11 April at 16h00, by 22h00 these homes were gone, as the Palmiet River changed course when the bridge blocked up with vegetation and solid waste, resulting in the river scouring out this section of the settlement. (Photo: Cathy Sutherland)

Sutherland noted it was important for the state to mobilise its resources to support what locals were doing.

The project at Quarry Road is a work in progress, and they are learning as they go along – but it worked. Despite being a high-risk area, no lives were lost to drowning in this settlement during the April floods.

This community-based early-warning system is the only one of its kind, but Tooley said the intention was to replicate it across other areas in the city, requiring close collaboration between the City, residents, academia and NGOs.

The municipality was in talks with the World Bank and other funders to develop resources to replicate the system in all 187 informal settlements on floodplains in the city.

“The important lesson is that… if the community doesn’t get involved in understanding the risks and understanding the language related to risk, the information of risk warnings is very difficult for them to respond to,” said Tooley.

WhatsApp group chat with eThekwini Municipality officials, UKZN researchers and community members living along Palmiet River during the floods in 11 April 2022. (Screenshot from chat: Geoff Tooley, senior manager at the Coastal Stormwater and Catchment Management Department for eThekwini Municipality)

Through the university’s collaboration, Quarry Road residents became sensitised to understanding the science and the relative predictability of climate risks, and were prepared to respond to the risk.

Sutherland, whose research focuses on environmental governance in Durban, said a major problem during the KZN flood disaster was lack of geographical literacy – not only people in informal settlements, but in peri-urban areas and formal developments too.

“It’s taking the warning and translating it into: ‘what does it mean for me?’” said Tooley.

Sutherland said we don’t focus enough on understanding the basic geographic facts of where we live – such as what it means to live on clay soils or steep slopes, or where water moves when there’s heavy rain.

At the root of it all: the land crisis

Sutherland said eThekwini is under pressure to develop new land – whether in informal settlements in peri-urban areas or private developers in gated estates – and we’re not paying attention.

“It’s not just the bigger environmental assessments to stop that. It’s just basic geographic literacy. That’s what indigenous knowledge often has, and we’ve lost that.”

A huge reason so many lives had been lost and displaced in the KZN disaster was not because of the extreme rainfall, but because the infrastructure had not been prepared for it.

WhatsApp group chat with eThekwini Municipality officials, UKZN researchers and community members living along Palmiet River during the floods in 11 April 2022. (Screenshot from chat: Geoff Tooley, senior manager at the Coastal Stormwater and Catchment Management Department for eThekwini Municipality)

Sutherland said that along with understanding (geographical literacy) we need building regulations and controls on developing lands.

Since the last floods that hit KZN in 2019, Sutherland said eThekwini has been working to relocate and upgrade informal settlements, but it’s a difficult process, and not everyone wants to relocate.

“There’s been low delivery of low-cost housing and also the fact that people who live in informal settlements don’t want to move away from where they work and live.

“You don’t want to move onto the periphery of the city because then you’re going to make people vulnerable in other ways.”

Sutherland said that most of the deaths were in the peri-urban areas on the periphery of the city, not in informal settlements.

These peri-urban areas are under dual governance (traditional authority and municipality).

People were originally allocated land from a traditional authority within the homeland of KwaZulu.

In 2000, the municipality inherited this area under dual-governance – but there were no basic services, infrastructure services or drainage systems.

This makes the area prone to landslides during heavy rain and flooding – which is where most of the deaths occurred.

“It’s not just the people’s fault,” said Sutherland. “Because, you know, that’s like a legacy of apartheid. These large rural areas were never developed – all the infrastructure was put in Durban, but it wasn’t put in those areas.”

Bobby Peek, who is part of the Presidential Climate Commission and director of environmental justice NPO groundWork, said colonial planning played a role in the disaster.

“Durban was the first apartheid-designed city… and apartheid planning created poorly constructed townships and a division and duality of managing Durban by the Ingonyama Trust and the eThekwini Municipality.”

Drone image of Quarry Road Informal Settlement located ona narrow flood plain of the Palmiet River, a high risk area prone to flooding, after heavy rainfall, 13 April 2022. (Photo: Dr. Viloshin Govendet, Architect and Lecturer for the School of Built Environment and Development Studies at the University of KwaZulu-Natal)

Peek suggested that the commission should focus on providing climate-resilient housing in informal settlements across the city.

“Dealing with the loss and damage is more than just an issue of climate finance and the confused nature in which it is proposed. It is an issue of climate debt and reparations.”

Sutherland suggested the municipality needed to work in partnership with the traditional authority and residents to develop infrastructure in those areas.

“Across South Africa the poor and the most vulnerable absorb the cost of social unrest, they absorb the cost of Covid. And now they’re absorbing the cost of flooding. It’s just so much for people to bear.”

Municipalities needed to get the basics right – providing water, sanitation, stormwater pathways and waste management.

“The people will do a lot of the other things themselves.” DM/OBP

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R25.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.